In linguistics, syntax is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure (constituency), agreement, the nature of crosslinguistic variation, and the relationship between form and meaning (semantics). There are numerous approaches to syntax that differ in their central assumptions and goals.

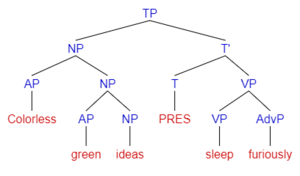

Phrase structure rules are a type of rewrite rule used to describe a given language's syntax and are closely associated with the early stages of transformational grammar, proposed by Noam Chomsky in 1957. They are used to break down a natural language sentence into its constituent parts, also known as syntactic categories, including both lexical categories and phrasal categories. A grammar that uses phrase structure rules is a type of phrase structure grammar. Phrase structure rules as they are commonly employed operate according to the constituency relation, and a grammar that employs phrase structure rules is therefore a constituency grammar; as such, it stands in contrast to dependency grammars, which are based on the dependency relation.

In linguistics, transformational grammar (TG) or transformational-generative grammar (TGG) is part of the theory of generative grammar, especially of natural languages. It considers grammar to be a system of rules that generate exactly those combinations of words that form grammatical sentences in a given language and involves the use of defined operations to produce new sentences from existing ones.

Lexical semantics, as a subfield of linguistic semantics, is the study of word meanings. It includes the study of how words structure their meaning, how they act in grammar and compositionality, and the relationships between the distinct senses and uses of a word.

In English grammar, an adverbial is a word or a group of words that modifies or more closely defines the sentence or the verb. Look at the examples below:

A garden-path sentence is a grammatically correct sentence that starts in such a way that a reader's most likely interpretation will be incorrect; the reader is lured into a parse that turns out to be a dead end or yields a clearly unintended meaning. "Garden path" refers to the saying "to be led down [or up] the garden path", meaning to be deceived, tricked, or seduced. In A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (1926), Fowler describes such sentences as unwittingly laying a "false scent".

Nonsense is a communication, via speech, writing, or any other symbolic system, that lacks any coherent meaning. In ordinary usage, nonsense is sometimes synonymous with absurdity or the ridiculous. Many poets, novelists and songwriters have used nonsense in their works, often creating entire works using it for reasons ranging from pure comic amusement or satire, to illustrating a point about language or reasoning. In the philosophy of language and philosophy of science, nonsense is distinguished from sense or meaningfulness, and attempts have been made to come up with a coherent and consistent method of distinguishing sense from nonsense. It is also an important field of study in cryptography regarding separating a signal from noise.

A word salad is a "confused or unintelligible mixture of seemingly random words and phrases", most often used to describe a symptom of a neurological or mental disorder. The name schizophasia is used in particular to describe the confused language that may be evident in schizophrenia. The words may or may not be grammatically correct, but they are semantically confused to the point that the listener cannot extract any meaning from them. The term is often used in psychiatry as well as in theoretical linguistics to describe a type of grammatical acceptability judgement by native speakers, and in computer programming to describe textual randomization.

Syntactic Structures is an important work in linguistics by American linguist Noam Chomsky, originally published in 1957. A short monograph of about a hundred pages, it is recognized as one of the most significant and influential linguistic studies of the 20th century. It contains the now-famous sentence "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously", which Chomsky offered as an example of a grammatically correct sentence that has no discernible meaning, thus arguing for the independence of syntax from semantics.

Poverty of the stimulus (POS) is the controversial argument from linguistics that children are not exposed to rich enough data within their linguistic environments to acquire every feature of their language. This is considered evidence contrary to the empiricist idea that language is learned solely through experience. The claim is that the sentences children hear while learning a language do not contain the information needed to develop a thorough understanding of the grammar of the language.

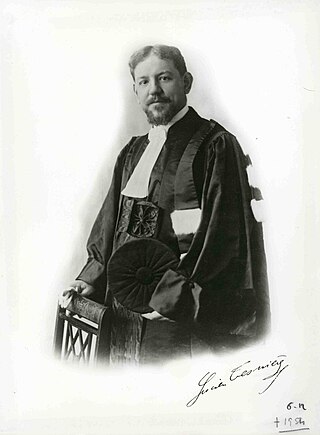

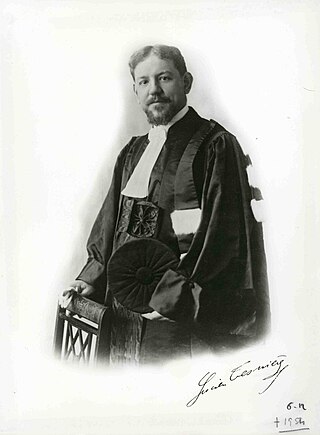

Lucien Tesnière was a prominent and influential French linguist. He was born in Mont-Saint-Aignan on May 13, 1893. As a senior lecturer at the University of Strasbourg (1924) and later professor at the University of Montpellier (1937), he published many papers and books on Slavic languages. However, his importance in the history of linguistics is based mainly on his development of an approach to the syntax of natural languages that would become known as dependency grammar. He presented his theory in his book Éléments de syntaxe structurale, published posthumously in 1959. In the book he proposes a sophisticated formalization of syntactic structures, supported by many examples from a diversity of languages. Tesnière died in Montpellier on December 6, 1954.

The theta-criterion is a constraint on x-bar theory that was first proposed by Noam Chomsky as a rule within the system of principles of the government and binding theory, called theta-theory (θ-theory). As theta-theory is concerned with the distribution and assignment of theta-roles, the theta-criterion describes the specific match between arguments and theta-roles (θ-roles) in logical form (LF):

An inauthentic text is a computer-generated expository document meant to appear as genuine, but which is actually meaningless. Frequently they are created in order to be intermixed with genuine documents and thus manipulate the results of search engines, as with Spam blogs. They are also carried along in email in order to fool spam filters by giving the spam the superficial characteristics of legitimate text.

"Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo" is a grammatically correct sentence in English that is often presented as an example of how homonyms and homophones can be used to create complicated linguistic constructs through lexical ambiguity. It has been discussed in literature in various forms since 1967, when it appeared in Dmitri Borgmann's Beyond Language: Adventures in Word and Thought.

The term linguistic performance was used by Noam Chomsky in 1960 to describe "the actual use of language in concrete situations". It is used to describe both the production, sometimes called parole, as well as the comprehension of language. Performance is defined in opposition to "competence"; the latter describes the mental knowledge that a speaker or listener has of language.

In linguistics, grammaticality is determined by the conformity to language usage as derived by the grammar of a particular speech variety. The notion of grammaticality rose alongside the theory of generative grammar, the goal of which is to formulate rules that define well-formed, grammatical, sentences. These rules of grammaticality also provide explanations of ill-formed, ungrammatical sentences.

In linguistics, well-formedness is the quality of a clause, word, or other linguistic element that conforms to the grammar of the language of which it is a part. Well-formed words or phrases are grammatical, meaning they obey all relevant rules of grammar. In contrast, a form that violates some grammar rule is ill-formed and does not constitute part of the language.

In linguistics and grammar, Avalency refers to the property of a predicate, often a verb, taking no arguments. Valency refers to how many and what kinds of arguments a predicate licenses—i.e. what arguments the predicate selects grammatically. Avalent verbs are verbs which have no valency, meaning that they have no logical arguments, such as subject or object. Languages known as pro-drop or null-subject languages do not require clauses to have an overt subject when the subject is easily inferred, meaning that a verb can appear alone. However, non-null-subject languages such as English require a pronounced subject in order for a sentence to be grammatical. This means that the avalency of a verb is not readily apparent, because, despite the fact that avalent verbs lack arguments, the verb nevertheless has a subject. According to some, avalent verbs may have an inserted subject, which is syntactically required, yet semantically meaningless, making no reference to anything that exists in the real world. An inserted subject is referred to as a pleonastic, or expletive it. Because it is semantically meaningless, pleonastic it is not considered a true argument, meaning that a verb with this it as the subject is truly avalent. However, others believe that it represents a quasi-argument, having no real-world referent, but retaining certain syntactic abilities. Still others consider it to be a true argument, meaning that it is referential, and not merely a syntactic placeholder. There is no general consensus on how it should be analyzed under such circumstances, but determining the status of it as a non-argument, a quasi-argument, or a true argument, will help linguists to understand what verbs, if any, are truly avalent. A common example of such verbs in many languages is the set of verbs describing weather. In providing examples for the avalent verbs below, this article must assume the analysis of pleonastic it, but will delve into the other two analyses following the examples.

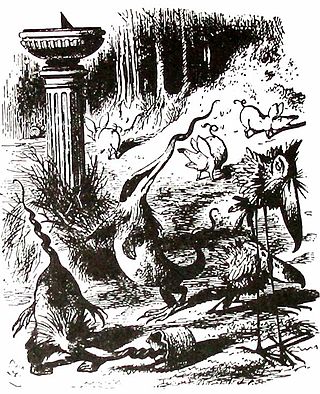

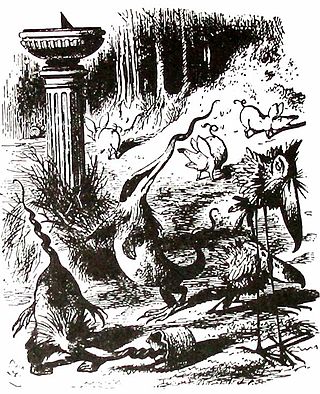

A Jabberwocky sentence is a type of sentence of interest in neurolinguistics. Jabberwocky sentences take their name from the language of Lewis Carroll's well-known poem "Jabberwocky". In the poem, Carroll uses correct English grammar and syntax, but many of the words are made up and merely suggest meaning. A Jabberwocky sentence is therefore a sentence which uses correct grammar and syntax but contains nonsense words, rendering it semantically meaningless.

In linguistics, the autonomy of syntax is the assumption that syntax is arbitrary and self-contained with respect to meaning, semantics, pragmatics, discourse function, and other factors external to language. The autonomy of syntax is advocated by linguistic formalists, and in particular by generative linguistics, whose approaches have hence been called autonomist linguistics.