Related Research Articles

Antipsychotics, also known as neuroleptics, are a class of psychotropic medication primarily used to manage psychosis, principally in schizophrenia but also in a range of other psychotic disorders. They are also the mainstay together with mood stabilizers in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

Mania, also known as manic syndrome, is a mental and behavioral disorder defined as a state of abnormally elevated arousal, affect, and energy level, or "a state of heightened overall activation with enhanced affective expression together with lability of affect." During a manic episode, an individual will experience rapidly changing emotions and moods, highly influenced by surrounding stimuli. Although mania is often conceived as a "mirror image" to depression, the heightened mood can be either euphoric or dysphoric. As the mania intensifies, irritability can be more pronounced and result in anxiety or anger.

A mood stabilizer is a psychiatric medication used to treat mood disorders characterized by intense and sustained mood shifts, such as bipolar disorder and the bipolar type of schizoaffective disorder.

Psychosis is a condition of the mind that results in difficulties determining what is real and what is not real. Symptoms may include delusions and hallucinations, among other features. Additional symptoms are incoherent speech and behavior that is inappropriate for a given situation. There may also be sleep problems, social withdrawal, lack of motivation, and difficulties carrying out daily activities. Psychosis can have serious adverse outcomes.

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by continuous or relapsing episodes of psychosis. Major symptoms include hallucinations, delusions and disorganized thinking. Other symptoms include social withdrawal and flat affect. Symptoms typically develop gradually, begin during young adulthood, and in many cases are resolved. There is no objective diagnostic test; diagnosis is based on observed behavior, a psychiatric history that includes the person's reported experiences, and reports of others familiar with the person. For a diagnosis of schizophrenia, the described symptoms need to have been present for at least six months or one month. Many people with schizophrenia have other mental disorders, especially substance use disorders, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders and obsessive–compulsive disorder.

A psychiatric or psychotropic medication is a psychoactive drug taken to exert an effect on the chemical makeup of the brain and nervous system. Thus, these medications are used to treat mental illnesses. These medications are typically made of synthetic chemical compounds and are usually prescribed in psychiatric settings, potentially involuntarily during commitment. Since the mid-20th century, such medications have been leading treatments for a broad range of mental disorders and have decreased the need for long-term hospitalization, thereby lowering the cost of mental health care. The recidivism or rehospitalization of the mentally ill is at a high rate in many countries, and the reasons for the relapses are under research.

The atypical antipsychotics (AAP), also known as second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and serotonin–dopamine antagonists (SDAs), are a group of antipsychotic drugs largely introduced after the 1970s and used to treat psychiatric conditions. Some atypical antipsychotics have received regulatory approval for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, irritability in autism, and as an adjunct in major depressive disorder.

Schizoaffective disorder is a mental disorder characterized by abnormal thought processes and an unstable mood. This diagnosis requires symptoms of both schizophrenia and a mood disorder: either bipolar disorder or depression. The main criterion is the presence of psychotic symptoms for at least two weeks without any mood symptoms. Schizoaffective disorder can often be misdiagnosed when the correct diagnosis may be psychotic depression, bipolar I disorder, schizophreniform disorder, or schizophrenia. This is a problem as treatment and prognosis differ greatly for most of these diagnoses.

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia or the dopamine hypothesis of psychosis is a model that attributes the positive symptoms of schizophrenia to a disturbed and hyperactive dopaminergic signal transduction. The model draws evidence from the observation that a large number of antipsychotics have dopamine-receptor antagonistic effects. The theory, however, does not posit dopamine overabundance as a complete explanation for schizophrenia. Rather, the overactivation of D2 receptors, specifically, is one effect of the global chemical synaptic dysregulation observed in this disorder.

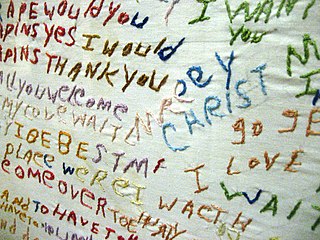

Thought broadcasting is a type of delusional condition in which the affected person believes that others can hear their inner thoughts, despite a clear lack of evidence. The person may believe that either those nearby can perceive their thoughts or that they are being transmitted via mediums such as television, radio or the internet. Different people can experience thought broadcasting in different ways. Thought broadcasting is most commonly found among people that have a psychotic disorder, specifically schizophrenia.

Psychotic depression, also known as depressive psychosis, is a major depressive episode that is accompanied by psychotic symptoms. It can occur in the context of bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder. It can be difficult to distinguish from schizoaffective disorder, a diagnosis that requires the presence of psychotic symptoms for at least two weeks without any mood symptoms present. Unipolar psychotic depression requires that psychotic symptoms occur during severe depressive episodes, although residual psychotic symptoms may also be present in between episodes. Diagnosis using the DSM-5 involves meeting the criteria for a major depressive episode, along with the criteria for "mood-congruent or mood-incongruent psychotic features" specifier.

Schizophreniform disorder is a mental disorder diagnosed when symptoms of schizophrenia are present for a significant portion of time, but signs of disturbance are not present for the full six months required for the diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Bipolar disorder in children, or pediatric bipolar disorder (PBD), is a rare and controversial mental disorder in children and adolescents. PBD is hypothesized to be like bipolar disorder (BD) in adults, thus is proposed as an explanation for periods of extreme shifts in mood called mood episodes. These shifts alternate between periods of depressed or irritable moods and periods of abnormally elevated moods called manic or hypomanic episodes. Mixed mood episodes can occur when a child or adolescent with PBD experiences depressive and manic symptoms simultaneously. Mood episodes of children and adolescents with PBD deviate from general shifts in mood experienced by children and adolescents because mood episodes last for long periods of time and cause severe disruptions to an individual's life. There are three known forms of PBD: Bipolar I, Bipolar II, and Bipolar Not Otherwise Specified (NOS). Just as in adults, bipolar I is also the most severe form of PBD in children and adolescents, and can impair sleep, general function, and lead to hospitalization. Bipolar NOS is the mildest form of PBD in children and adolescents. The average age of onset of PBD remains unclear, but reported ages of onset range from 5 years of age to 19 years of age. PBD is typically more severe and has a poorer prognosis than bipolar disorder with onset in late-adolescence or adulthood.

In medicine, a prodrome is an early sign or symptom that often indicates the onset of a disease before more diagnostically specific signs and symptoms develop. It is derived from the Greek word prodromos, meaning "running before". Prodromes may be non-specific symptoms or, in a few instances, may clearly indicate a particular disease, such as the prodromal migraine aura.

The glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia models the subset of pathologic mechanisms of schizophrenia linked to glutamatergic signaling. The hypothesis was initially based on a set of clinical, neuropathological, and, later, genetic findings pointing at a hypofunction of glutamatergic signaling via NMDA receptors. While thought to be more proximal to the root causes of schizophrenia, it does not negate the dopamine hypothesis, and the two may be ultimately brought together by circuit-based models. The development of the hypothesis allowed for the integration of the GABAergic and oscillatory abnormalities into the converging disease model and made it possible to discover the causes of some disruptions.

Postpartum psychosis(PPP), also known as puerperal psychosis or peripartum psychosis, involves the abrupt onset of psychotic symptoms shortly following childbirth, typically within two weeks of delivery but less than 4 weeks postpartum. PPP is a condition currently represented under "Brief Psychotic Disorder" in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Volume V (DSM-V). Symptoms may include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech (e.g, incoherent speech), and/or abnormal motor behavior (e.g., catatonia). Other symptoms frequently associated with PPP include confusion, disorganized thought, severe difficulty sleeping, variations of mood disorders (including depression, agitation, mania, or a combination of the above), as well as cognitive features such as consciousness that comes and goes (waxing and waning) or disorientation.

Childhood schizophrenia is similar in characteristics of schizophrenia that develops at a later age, but has an onset before the age of 13 years, and is more difficult to diagnose. Schizophrenia is characterized by positive symptoms that can include hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized speech; negative symptoms, such as blunted affect and avolition and apathy, and a number of cognitive impairments. Differential diagnosis is problematic since several other neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder, language disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, also have signs and symptoms similar to childhood-onset schizophrenia.

The causes of schizophrenia that underlie the development of schizophrenia, a psychiatric disorder, are complex and not clearly understood. A number of hypotheses including the dopamine hypothesis, and the glutamate hypothesis have been put forward in an attempt to explain the link between altered brain function and the symptoms and development of schizophrenia.

The diagnosis of schizophrenia, a psychotic disorder, is based on criteria in either the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Clinical assessment of schizophrenia is carried out by a mental health professional based on observed behavior, reported experiences, and reports of others familiar with the person. Diagnosis is usually made by a psychiatrist. Associated symptoms occur along a continuum in the population and must reach a certain severity and level of impairment before a diagnosis is made. Schizophrenia has a prevalence rate of 0.3-0.7% in the United States

Dopamine supersensitivity psychosis is a hypothesis that attempts to explain the phenomenon in which psychosis occurs despite treatment with escalating doses of antipsychotics. Dopamine supersensitivity may be caused by the dopamine receptor D2 antagonizing effect of antipsychotics, causing a compensatory increase in D2 receptors within the brain that sensitizes neurons to endogenous release of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Because psychosis is thought to be mediated—at least in part—by the activity of dopamine at D2 receptors, the activity of dopamine in the presence of supersensitivity may paradoxically give rise to worsening psychotic symptoms despite antipsychotic treatment at a given dose. This phenomenon may co-occur with tardive dyskinesia, a rare movement disorder that may also be due to dopamine supersensitivity.

References

- ↑ Schrimpf LA, Aggarwal A, Lauriello J (June 2018). "Psychosis". Continuum. 24 (3, BEHAVIORAL NEUROLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY): 845–860. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000602. PMID 29851881. S2CID 243933980.

- 1 2 3 4 Miller NS, Cocores JA, Belkin B (1991-03-01). "Nicotine Dependence: Diagnosis, Chemistry and Pharmacological Treatments". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 3 (1): 47–53. doi:10.3109/10401239109147967. ISSN 1040-1237. S2CID 38633974.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dobri ML, Diaz AP, Selvaraj S, Quevedo J, Walss-Bass C, Soares JC, Sanches M (March 2022). "The Limits between Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder: What Do Magnetic Resonance Findings Tell Us?". Behavioral Sciences. 12 (3): 78. doi: 10.3390/bs12030078 . PMC 8944966 . PMID 35323397.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Moncrieff J, Gupta S, Horowitz MA (January 2020). "Barriers to stopping neuroleptic (antipsychotic) treatment in people with schizophrenia, psychosis or bipolar disorder". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 10: 2045125320937910. doi:10.1177/2045125320937910. PMC 7338640 . PMID 32670542.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jann MW (December 2014). "Diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorders in adults: a review of the evidence on pharmacologic treatments". American Health & Drug Benefits. 7 (9): 489–499. PMC 4296286 . PMID 25610528.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Patel KR, Cherian J, Gohil K, Atkinson D (September 2014). "Schizophrenia: overview and treatment options". P & T. 39 (9): 638–645. PMC 4159061 . PMID 25210417.

- 1 2 3 Cosgrove VE, Suppes T (May 2013). "Informing DSM-5: biological boundaries between bipolar I disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia". BMC Medicine. 11: 127. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-127 . PMC 3653750 . PMID 23672587.

- 1 2 Geoffroy PA, Etain B, Houenou J (October 2013). "Gene x environment interactions in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: evidence from neuroimaging". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 4: 136. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00136 . PMC 3796286 . PMID 24133464.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ruderfer DM, Ripke S, McQuillin A, Boocock J, Stahl EA, Pavlides JM, et al. (June 2018). "Genomic Dissection of Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia, Including 28 Subphenotypes". Cell. 173 (7): 1705–1715.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.046. PMC 6432650 . PMID 29906448.

- 1 2 3 Yüksel C, McCarthy J, Shinn A, Pfaff DL, Baker JT, Heckers S, et al. (July 2012). "Gray matter volume in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with psychotic features". Schizophrenia Research. 138 (2–3): 177–182. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.03.003. PMC 3372612 . PMID 22445668.

- ↑ Picard H, Amado I, Mouchet-Mages S, Olié JP, Krebs MO (January 2008). "The role of the cerebellum in schizophrenia: an update of clinical, cognitive, and functional evidences". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 34 (1): 155–172. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm049. PMC 2632376 . PMID 17562694.

- ↑ Arnone D, Cavanagh J, Gerber D, Lawrie SM, Ebmeier KP, McIntosh AM (September 2009). "Magnetic resonance imaging studies in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: meta-analysis". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 195 (3): 194–201. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.059717 . PMID 19721106.

- ↑ Watson DR, Anderson JM, Bai F, Barrett SL, McGinnity TM, Mulholland CC, et al. (February 2012). "A voxel based morphometry study investigating brain structural changes in first episode psychosis". Behavioural Brain Research. 227 (1): 91–99. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2011.10.034. PMID 22056751. S2CID 8420433.(subscription required)

- ↑ Starkstein SE, Robinson RG, Price TR (August 1987). "Comparison of cortical and subcortical lesions in the production of poststroke mood disorders". Brain. 110 (4): 1045–1059. doi:10.1093/brain/110.4.1045. PMID 3651794.

- 1 2 3 "Bipolar Disorder in Adults". National Institute of Mental Health. National Institutes of Health. 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Schizophrenia". National Institute of Mental Health. National Institutes of Health. 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2014.