A Chinese radical or indexing component is a graphical component of a Chinese character under which the character is traditionally listed in a Chinese dictionary. This component is often a semantic indicator similar to a morpheme, though sometimes it may be a phonetic component or even an artificially extracted portion of the character. In some cases the original semantic or phonological connection has become obscure, owing to changes in character meaning or pronunciation over time.

Shuowen Jiezi is an ancient Chinese dictionary compiled by Xu Shen during the Eastern Han dynasty. Although not the first comprehensive Chinese character dictionary, it was the first to analyze the structure of the characters and to give the rationale behind them, as well as the first to use the principle of organization by sections with shared components called "radicals".

King Zhou was the pejorative posthumous name given to Di Xin of Shang or King Shou of Shang, the last king of the Shang dynasty of ancient China. He is also called Zhou Xin. In Chinese, his name Zhòu also refers to a horse crupper, the part of a saddle or harness that is most likely to be soiled by the horse. It is not to be confused with the name of the succeeding dynasty, which has a different character and pronunciation.

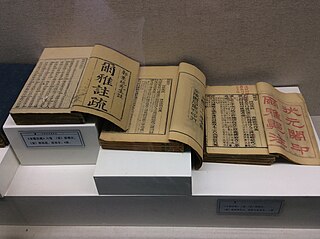

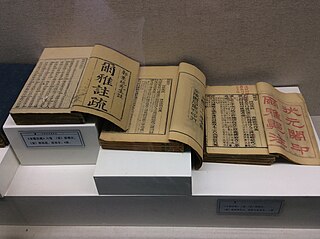

The Erya or Erh-ya is the first surviving Chinese dictionary. The sinologist Bernhard Karlgren concluded that "the major part of its glosses must reasonably date from the 3rd century BC."

Traditional Chinese marriage is a ceremonial ritual within Chinese societies that involves not only a union between spouses but also a union between the two families of a man and a woman, sometimes established by pre-arrangement between families. Marriage and family are inextricably linked, which involves the interests of both families. Within Chinese culture, romantic love and monogamy were the norm for most citizens. Around the end of primitive society, traditional Chinese marriage rituals were formed, with deer skin betrothal in the Fuxi era, the appearance of the "meeting hall" during the Xia and Shang dynasties, and then in the Zhou dynasty, a complete set of marriage etiquette gradually formed. The richness of this series of rituals proves the importance the ancients attached to marriage. In addition to the unique nature of the "three letters and six rituals", monogamy, remarriage and divorce in traditional Chinese marriage culture are also distinctive.

Empress Wu, personal name Wu Xian, formally known as Empress Mu, was an empress of the state of Shu Han during the Three Kingdoms period. She was the last wife and the only empress of Liu Bei, the founding emperor of Shu Han, and a younger sister of Wu Yi.

Empress Pan, personal name Pan Shu, was an empress of the state of Eastern Wu during the Three Kingdoms period of China. She was the only empress of Wu's founding emperor, Sun Quan, even though he had a succession of wives before her. She was the mother of Sun Liang, Sun Quan's successor and the second emperor of Wu.

Tao Qian (132–194), courtesy name Gongzu, was a government official and warlord who lived during the late Eastern Han dynasty of China. He is best known for serving as the governor of Xu Province.

Cheng Bing, courtesy name Deshu, was an official and writer of the state of Eastern Wu during the Three Kingdoms period of China.

Hong or jiang is a Chinese dragon with two heads on each end in Chinese mythology, comparable with rainbow serpent legends in various cultures and mythologies.

The Three Obediences and Four Virtues is a set of moral principles and social code of behavior for maiden and married women in East Asian Confucianism, especially in ancient and imperial China. Women were to obey their fathers, husbands, and sons, and to be modest and moral in their actions and speech. Some imperial eunuchs both observed these principles themselves and enforced them in imperial harems, aristocratic households, and society at large.

Lady Saso is said to be the mother of Hyeokgeose of Silla first introduced in Samguk Yusa. Also known as the Sacred Mother of Mt. Seondo, legends say she was a princess from the Buyeo royal family. She gave birth to Hyeokgeose of Silla. Later, she was honored as great king by King Gyeongmyeong.

Princess Hwapyeong was the eldest daughter of King Yeongjo of Joseon and Royal Noble Consort Yeong of the Jeonui Lee clan, and Yeongjo's third daughter overall.

Princess Uisun was a Joseon Royal Family member who became the adopted daughter of Hyojong of Joseon and Queen Inseon, so she could marry the Aisin Gioro prince Dorgon and later, prince Bolo.

Zhuge Jing, courtesy name Zhongsi, was a Chinese military general and politician of Eastern Wu during the Three Kingdoms period of China. Though originally from Cao Wei, he was sent to Wu as a hostage during the rebellion of his father, Zhuge Dan, in 257. After his father's death in 258, Zhuge Jing continued to stay in Wu where he served as a general until the state's demise in 280 which ended the Three Kingdoms.

Duan Pidi was a Duan-Xianbei chieftain during the Jin dynasty (266–420) and Sixteen Kingdoms period. He was the brother of chieftain, Duan Jilujuan, and served as his general in Jin's war with the Han-Zhao state. After Jilujuan made peace with Han in 313, Pidi led his branch of the tribe to continue fighting Han from Jicheng. Pidi became the most powerful Jin vassal in the north, but his decision to kill his ally, Liu Kun and a civil war with his cousin, Duan Mopei severely weakened him. In 319, he was forced to flee to another Jin vassal, Shao Xu. He was eventually captured by the Later Zhao in 321, and despite receiving favourable treatment from its ruler, Shi Le, he would later be executed in fear of that he would rebel.

Wang Yan, courtesy name Yifu, was a Chinese politician. He served as a minister and was one of the pure conversation leaders of the Jin dynasty (266–420). During the reign of Emperor Hui of Jin, Wang Yan grew popular among the court for his mastery in Qingtan and for being a patron of Xuanxue. Wang Yan vacillated between the warring princes during the War of the Eight Princes until he ended up with Sima Yue, who gave him a considerable amount of power in his administration. After Yue died in April 311, Wang Yan led his funeral procession but was ambushed and later executed by the Han-Zhao general, Shi Le at Ningping City. Though a bright scholar, Wang Yan was often associated by traditional historians as one of the root causes for Western Jin's demise due to his influential beliefs.

Pei Wei (267–300), courtesy name Yimin, was a Chinese essayist, philosopher, physician, and politician of the Western Jin dynasty. He was the cousin of Jia Nanfeng and rose to prominence during the reign of her husband, the Emperor Hui of Jin. Pei Wei was seen by traditional historian as one of Empress Jia's exemplary supporters along with Zhang Hua and Jia Mo. He pushed for a number of significant reforms during his tenure which met with mixed success before his execution by the Prince of Zhao, Sima Lun, in 300 following Sima Lun's coup.

Handan Chun, courtesy name Zishu or Zili, also known as Handan Zhu, was a writer, calligrapher, and official from Yingchuan Commandery who served the state of Cao Wei during the early 3rd century. As a calligrapher, he was an expert in many types of scripts and was one of the first scholars to study the Shuowen Jiezi. He is credited with restoring the archaic tadpole script tradition. His most famous work is the Xiaolin (笑林), a collection of humorous anecdotes.

Xun Cai (荀采) was a Chinese noblewoman and poet from the late Eastern Han dynasty to the early Three Kingdoms period.