The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the American Civil War against the United States's Union Navy.

Mary Elizabeth Jenkins Surratt was an American boarding house owner in Washington, D.C., who was convicted of taking part in the conspiracy which led to the assassination of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln in 1865. Sentenced to death, she was hanged and became the first woman executed by the U.S. federal government. She maintained her innocence until her death, and the case against her was and remains controversial. Surratt was the mother of John Surratt, who was later tried in the conspiracy, but was not convicted.

The Chesapeake Affair was an international diplomatic incident that occurred during the American Civil War. On December 7, 1863, Confederate sympathizers from the Maritime Provinces captured the American steamer Chesapeake off the coast of Cape Cod. The expedition was planned and led by Vernon Guyon Locke (1827–1890) of Nova Scotia and John Clibbon Brain (1840–1906). When George Wade of New Brunswick killed one of the American crew, the Confederacy claimed its first fatality in New England waters.

CSS Shenandoah, formerly Sea King and later El Majidi, was an iron-framed, teak-planked, full-rigged sailing ship with auxiliary steam power chiefly known for her actions under Lieutenant Commander James Waddell as part of the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War.

CSS Sumter, converted from the 1859-built merchant steamer Habana, was the first steam cruiser of the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War. She operated as a commerce raider in the Caribbean and in the Atlantic Ocean against Union merchant shipping between July and December 1861, taking eighteen prizes, but was trapped in Gibraltar by Union Navy warships. Decommissioned, she was sold in 1862 to the British office of a Confederate merchant and renamed Gibraltar, successfully running the Union blockade in 1863 and surviving the war.

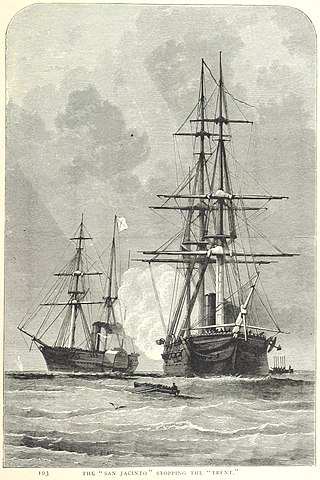

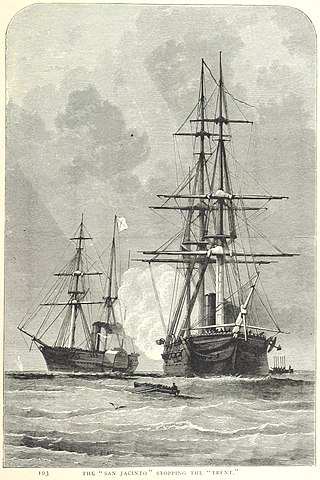

The first USS San Jacinto was an early screw frigate in the United States Navy during the mid-19th century. She was named for the San Jacinto River, site of the Battle of San Jacinto during the Texas Revolution. She is perhaps best known for her role in the Trent Affair of 1861.

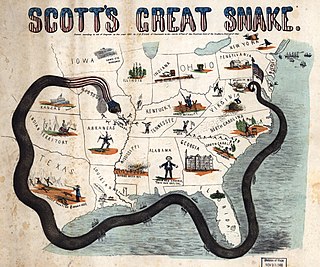

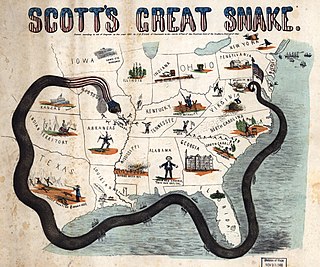

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

Nathaniel Beverley Tucker was an American journalist, printer, and diplomat. During the American Civil War he was a Confederate States (Southern) economic agent in France, England, and Canada, and also a secret representative in the North.

Louis J. Weichmann was an American clerk who was one of the chief witnesses for the prosecution in the trial following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Previously, he had also been a suspect in the conspiracy because of his association with Mary Surratt's family.

James Dunwoody Bulloch was the Confederacy's chief foreign agent in Great Britain during the American Civil War. Based in Liverpool, he operated blockade runners and commerce raiders that provided the Confederacy with its only source of hard currency. Bulloch arranged for the purchase by British merchants of Confederate cotton, as well as the dispatch of armaments and other war supplies to the South. He also oversaw the construction and purchase of several ships designed at ruining Northern shipping during the Civil War, including CSS Florida, CSS Alabama, CSS Stonewall, and CSS Shenandoah. Due to him being a Confederate secret agent, Bulloch was not included in the general amnesty that came after the Civil War and therefore decided to stay in Liverpool, becoming the director of the Liverpool Nautical College and the Orphan Boys Asylum.

The Confederate Secret Service refers to any of a number of official and semi-official secret service organizations and operations conducted by the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. Some of the organizations were under the direction of the Confederate government, others operated independently with government approval, while still others were either completely independent of the government or operated with only its tacit acknowledgment.

John Harrison Surratt Jr. was an American Confederate spy who was accused of plotting with John Wilkes Booth to kidnap U.S. President Abraham Lincoln; he was also suspected of involvement in the Abraham Lincoln assassination. His mother, Mary Surratt, was convicted of conspiracy by a military tribunal and hanged; she owned the boarding house that the conspirators used as a safe house and to plot the scheme.

The Georgiana was a brig-rigged, iron hulled, propeller steamer belonging to the Confederate States Navy during the American Civil War. Reputedly intended to become the "most powerful" cruiser in the Confederate fleet once her guns were mounted, she was never used in battle. On her maiden voyage from Scotland, where she was built, she encountered Union Navy ships engaged in a blockade of Charleston, South Carolina, and was heavily damaged before being scuttled by her captain. The wreck was discovered in 1965 and lies in the shallow waters of Charleston's harbor.

The Confederate privateers were privately owned ships that were authorized by the government of the Confederate States of America to attack the shipping of the United States. Although the appeal was to profit by capturing merchant vessels and seizing their cargoes, the government was most interested in diverting the efforts of the Union Navy away from the blockade of Southern ports, and perhaps to encourage European intervention in the conflict.

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland remained officially neutral throughout the American Civil War (1861–1865). It legally recognized the belligerent status of the Confederate States of America (CSA) but never recognized it as a nation and neither signed a treaty with it nor ever exchanged ambassadors. Over 90 percent of Confederate trade with Britain ended, causing a severe shortage of cotton by 1862. Private British blockade runners sent munitions and luxuries to Confederate ports in return for cotton and tobacco. In Manchester, the massive reduction of available American cotton caused an economic disaster referred to as the Lancashire Cotton Famine. Despite the high unemployment, some Manchester cotton workers refused out of principle to process any cotton from America, leading to direct praise from President Lincoln, whose statue in Manchester bears a plaque which quotes his appreciation for the textile workers in "helping abolish slavery". Top British officials debated offering to mediate in the first 18 months, which the Confederacy wanted but the United States strongly rejected.

James Maury was one of the first United States diplomats and one of the first American consuls appointed overseas. In 1790 he was appointed to the Consulate of the United States in Liverpool, one of the first overseas consulates founded by the then fledgling United States of America. Maury held the position of consul for 39 years until he was removed from office by President Andrew Jackson in 1829.

George H Steuart was an American diplomat and Foreign Service officer, and one of the last consuls of the United States of America in Liverpool, England. He was a major benefactor of the Mary Ball Washington Museum and Library in Lancaster, Virginia, donating by deed of gift the Steuart Blakemore Building, formerly known as the Old Post Office.

Events from the year 1865 in the United States. The American Civil War ends with the surrender of the Confederate States, beginning the Reconstruction era of U.S. history.

Thomas Haines Dudley (1819-1893) was consul of the United States of America in Liverpool during the American Civil War. He was instrumental in leading efforts by the Federal Government to prevent British involvement in the war, and in particular in preventing blockade runners from Liverpool, such as the CSS Alabama, from assisting the Confederate war effort.

Throughout the American Civil War, blockade runners were seagoing steam ships that were used to get through the Union blockade that extended some 3,500 miles (5,600 km) along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico coastlines and the lower Mississippi River. The Confederate states were largely without industrial capability and could not provide the quantity of arms and other supplies needed to fight against the industrial North. To meet this need blockade runners were built in Scotland and England and were used to import the guns, ordnance and other supplies that the Confederacy desperately needed, in exchange for cotton that the British textile industry needed greatly. To penetrate the blockade, these relatively lightweight shallow draft ships, mostly built in British shipyards and specially designed for speed, but not suited for transporting large quantities of cotton, had to cruise undetected, usually at night, through the Union blockade. The typical blockade runners were privately owned vessels often operating with a letter of marque issued by the Confederate States of America. If spotted, the blockade runners would attempt to outmaneuver or simply outrun any Union ships on blockade patrol, often successfully.