Contemptus mundi, the "contempt of the world" and worldly concerns, is a theme in the intellectual life of both Classical Antiquity and of Christianity, [1] both in its mystical vein and its ambivalence towards secular life, that figures largely in the Western world's history of ideas. In inculcating a turn of mind that would lead to a state of serenity untrammeled by distracting material appetites and feverish emotional connections, which the Greek philosophers called ataraxia , it drew upon the assumptions of Stoicism and a neoplatonism that was distrustful of deceptive and spurious appearances. In the familiar rhetorical polarity in Hellenic philosophy between the active and the contemplative life, which Christians, who expressly rejected "the World, the Flesh and the Devil", [2] might exemplify as the way of Martha and the way of Mary, contemptus mundi assumed that only the contemplative life was of lasting value and the world an empty shell, a vanity.

In the classical canon, Cicero's Tusculanae Disputationes , essays on achieving Stoic stability of emotions, with rhetorical subjects such as "Contempt of death", was taken up definitively by Boethius in his Consolations of Philosophy , during the troubled closing phase of Late Antiquity. The Latin tradition of dispraise of the public world adapted by Christian moralists, focused especially on the fickleness of Fortune, and the evils exposed in the Latin satire became a mainstay of Christian penitential literature.

Among early Christians, Eucherius of Lyon, an aristocratic and high-ranking ecclesiastic in the fifth-century Christian Church of Gaul, wrote to his kinsman a widely read letter de contemptu mundi, an expression of the despair for the present and future of the world in its last throes. Contempt for the world provided intellectual underpinnings for the retreat into monasticism: when Saint Florentina, of the prominent Christian family of Hispania, founded her convent, her rule written by her brother Leander of Seville explicitly cited contempt for the world: Regula sive Libellus de institutione virginum et de contemptu mundi ad Florentinam sororem.

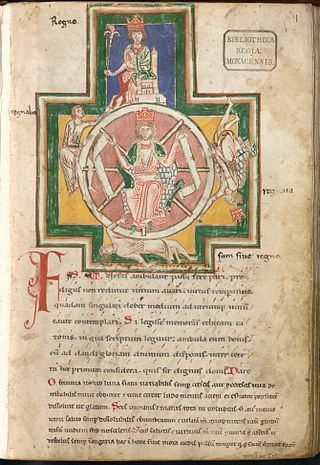

The medieval trope of contemptus mundi, drawing upon these converging traditions, pagan philosophy and Christian ascetic theology, [3] was fundamental to a medieval education. [4] A classic Christian expression is Bernard of Cluny's bitter 12th-century satire De contemptu mundi , founded in a deep sense of the transitory nature of secular joys and the abiding permanency of the spiritual life. His text made one of the Auctores octo morales , the "eight moral authors" that formed the central texts of medieval pedagogy.

In the early 12th century, when Adelard of Bath (c. 1080 - 1152) allegorized two contrasting figures to dispute De eodem et diverso; they were Philosophia and Philocosmia, "love of wisdom" and the "love of the world". [5] Adelard's contemporary, Henry of Huntington, in the dedicatory letter to his Historia Anglorum referred in passing to "those who taught the contempt of the world in schools". [6]

An aspect of contempt for this world reflects upon the ephemerality of all life, expressed in the literary rhetorical question of ubi sunt . Even as worldly a pope as Innocent III could write an essay "On the Misery of the Human Condition", De miseria humanae conditionis, which Geoffrey Chaucer is reputed to have rendered in English, in a translation now lost. [7] The theme had political ramifications within the Roman Church, as it was inextricably bound up with questions of apostolic poverty [8] which was roundly condemned, in the instance of the Humiliati, as heretical.

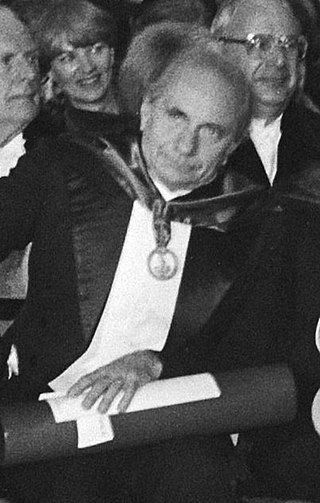

The waning of the dominant attitude of contemptus mundi that had informed elite culture, a development that gathered impetus during the second half of the 14th century, was a precursor to the emergence of the modern secular ethos, encouraging men to study material things with greater lucidity than before, as Georges Duby has observed, noting the turn taken in painting and sculpture toward the realistic delineation of aspects of material life. [9]

The theme of contemptus mundi continued to inform European poetry into the Early Modern period. [10] Contemptus mundi is a running theme in the poetry of William Drummond of Hawthornden, [11] and Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy and the devotional verse of Jeremy Taylor would serve as further examples. The recurrence of bubonic plague offered a concrete visitation of the frailty of this life for devotional texts, as early as John Donne. [12]

Contemptus mundi has been criticized as a pastoral of fear by the historian Jean Delumeau, [13] and M. B. Pranger found the trope "Speaking of God after Auschwitz" to function as a "modern form of contemptus mundi". [14]

The Canterbury Tales is a collection of twenty-four stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. It is widely regarded as Chaucer's magnum opus. The tales are presented as part of a story-telling contest by a group of pilgrims as they travel together from London to Canterbury to visit the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral. The prize for this contest is a free meal at the Tabard Inn at Southwark on their return.

Georges Duby was a French historian who specialised in the social and economic history of the Middle Ages. He ranks among the most influential medieval historians of the twentieth century and was one of France's most prominent public intellectuals from the 1970s to his death.

Guillaume de Machaut was a French composer and poet who was the central figure of the ars nova style in late medieval music. His dominance of the genre is such that modern musicologists use his death to separate the ars nova from the subsequent ars subtilior movement. Regarded as the most significant French composer and poet of the 14th century, he is often seen as the century's leading European composer.

The goliards were a group of generally young clergy in Europe who wrote satirical Latin poetry in the 12th and 13th centuries of the Middle Ages. They were chiefly clerics who served at or had studied at the universities of France, Germany, Spain, Italy, and England, who protested against the growing contradictions within the church through song, poetry and performance. Disaffected and not called to the religious life, they often presented such protests within a structured setting associated with carnival, such as the Feast of Fools, or church liturgy.

Poetry took numerous forms in medieval Europe, for example, lyric and epic poetry. The troubadours, trouvères, and the minnesänger are known for composing their lyric poetry about courtly love usually accompanied by an instrument.

Medieval literature is a broad subject, encompassing essentially all written works available in Europe and beyond during the Middle Ages. The literature of this time was composed of religious writings as well as secular works. Just as in modern literature, it is a complex and rich field of study, from the utterly sacred to the exuberantly profane, touching all points in-between. Works of literature are often grouped by place of origin, language, and genre.

Christian monasticism is the devotional practice of Christians who live ascetic and typically cloistered lives that are dedicated to Christian worship. It began to develop early in the history of the Christian Church, modeled upon scriptural examples and ideals, including those in the Old Testament, but was not mandated as an institution in the scriptures. It has come to be regulated by religious rules and, in modern times, the Canon law of the respective Christian denominations that have forms of monastic living. Those living the monastic life are known by the generic terms monks (men) and nuns (women). The word monk originated from the Greek μοναχός, itself from μόνος meaning 'alone'.

Solomon ibn Gabirol or Solomon ben Judah was an 11th-century Andalusian poet and Jewish philosopher in the Neo-Platonic tradition. He published over a hundred poems, as well as works of biblical exegesis, philosophy, ethics and satire. One source credits ibn Gabirol with creating a golem, possibly female, for household chores.

Henry of Huntingdon, the son of a canon in the diocese of Lincoln, was a 12th-century English historian and the author of Historia Anglorum, as "the most important Anglo-Norman historian to emerge from the secular clergy". He served as archdeacon of Huntingdon. The few details of Henry's life that are known originated from his own works and from a number of official records. He was brought up in the wealthy court of Robert Bloet of Lincoln, who became his patron.

Bernard of Cluny was a twelfth-century French Benedictine monk, best known as the author of De contemptu mundi, a long verse satire in Latin.

De Contemptu Mundi is the most well-known work of Bernard of Cluny. It is a 3,000 verse poem of stinging satire directed against the secular and religious failings he observed in the world around him. He spares no one; priests, nuns, bishops, monks, and even Rome itself are mercilessly scourged for their shortcomings. For this reason it was first printed by Matthias Flacius in Varia poemata de corrupto ecclesiae statu as one of his testes veritatis, or witnesses of the deep-seated corruption of medieval society and of the Church, and was often reprinted by Protestants in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

William of Saint-Amour was an early figure in thirteenth-century scholasticism, chiefly notable for his withering attacks on the friars.

Eucherius was a high-born and high-ranking ecclesiastic in the Christian church in Roman Gaul. He is remembered for his letters advocating extreme self-abnegation. From 439, he served as Archbishop of Lyon, and Henry Wace ranked him "the most distinguished occupant of that see" after Irenaeus. He is venerated as a saint within the Catholic Church.

Geoffrey of Vinsauf is a representative of the early medieval grammarian movement, termed preceptive grammar for its interest in teaching the ars poetica.

Consecrated life is a state of life in the Catholic Church lived by those faithful who are called to follow Jesus Christ in a more exacting way. It includes those in institutes of consecrated life, societies of apostolic life, as well as those living as hermits or consecrated virgins/widows.

New Monasticism is a diverse movement, not limited to a specific religious denomination or church and including varying expressions of contemplative life. These include evangelical Christian communities such as "Simple Way Community" and Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove's "Rutba House," European and Irish new monastic communities, such as that formed by Bernadette Flanagan, spiritual communities such as the "Community of the New Monastic Way" founded by feminist contemplative theologian Beverly Lanzetta, and "interspiritual" new monasticism, such as that developed by Rory McEntee and Adam Bucko. These communities expand upon traditional monastic wisdom, translating it into forms that can be lived out in contemporary lives "in the world."

Cosmographia ("Cosmography"), also known as De mundi universitate, is a Latin philosophical allegory, dealing with the creation of the universe, by the twelfth-century author Bernardus Silvestris. In form, it is a prosimetrum, in which passages of prose alternate with verse passages in various classical meters. The philosophical basis of the work is the Platonism of contemporary philosophers associated with the cathedral school of Chartres—one of whom, Thierry of Chartres, is the dedicatee of the work. According to a marginal note in one early manuscript, the Cosmographia was recited before Pope Eugene III when he was traveling in France (1147–48).

Medieval debate poetry refers to a genre of poems popular in England and France during the late medieval period.

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century until after the Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval philosophy, understood as a project of independent philosophical inquiry, began in Baghdad, in the middle of the 8th century, and in France, in the itinerant court of Charlemagne, in the last quarter of the 8th century. It is defined partly by the process of rediscovering the ancient culture developed in Greece and Rome during the Classical period, and partly by the need to address theological problems and to integrate sacred doctrine with secular learning.

"Jerusalem the Golden" is a nineteenth-century Christian hymn by John Mason Neale. The text is from Neale's translation of a section of Bernard of Cluny's Latin verse satire De Contemptu Mundi.