Historical ceremonies of introducing a new monarch by a ceremony of coronation can be traced to classical antiquity, and further to the Ancient Near East (especially the "Crowns of Egypt").

Historical ceremonies of introducing a new monarch by a ceremony of coronation can be traced to classical antiquity, and further to the Ancient Near East (especially the "Crowns of Egypt").

This article needs additional citations for verification .(April 2013) |

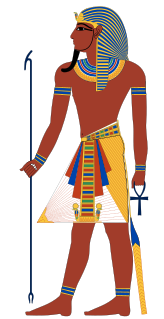

Pharaohs of Ancient Egypt were believed to be divine. In the coronation ceremony, the pharaoh was transformed into a god by means of his union with the royal ka , or life-force of the soul. All previous kings of Egypt had possessed this royal ka, and at his or her coronation, the monarch became divine as "one with the royal ka when his human form was overtaken by his immortal element, which flows through his whole being and dwells in it". [1] [ unreliable source? ] This made him the son of Ra, the sun god, Horus, the falcon god, and Osiris, the god of life, death and fertility. From the Middle Kingdom on, the Pharaoh also came to be seen as the son of Amon, the king of Egyptian gods, until his cult faded in later centuries. At his death, the king became fully divine, according to Egyptian belief, being assimilated with Osiris and Ra.

Upon the death of the reigning Pharaoh, his successor was named immediately, so that the nation's cosmic protection would continue unbroken. While the new monarch ascended the throne the very next day, the coronation ceremony did not take place until the first day of a new season, thus symbolising the beginning of a new era. The ceremony was usually carried out at Memphis by the high priest, who invested the new king with the necessary powers to continue his predecessors' work. [2] [ unreliable source? ]

As a permanent reminder to his people of his divine birthright, the Pharaoh wore various elements of royal regalia that varied depending upon the particular period in Egyptian history. Among these were a false beard made from goat's hair, identifying him with the god Osiris; a sceptre shaped like a shepherd's crook known as a Heka , which meant "ruler" and was often associated with magic; and a fly whip called the Nekhakha , symbol of his power and authority. The new monarch also wore a Shemset apron, while his back was protected by a bull's tail hanging from his belt, symbolic of strength, though this was later done away with. [3] [ unreliable source? ] He was invested with a crown during his coronation: depending on the historic period, the king might have been given the White Crown, or Hedjet (the crown of Upper Egypt), the Deshret or Red Crown (diadem of Lower Egypt), the Pschent or Sekhemti (the Double Crown, combining the White and the Red Crowns), the Nemes or striped headcloth, or the Khepresh or Blue Crown. The Pschent was generally used for the highest state occasions, [2] and was conferred on all Pharaohs from at least the First Dynasty on. [4] When the Hedjet was combined with red Ostrich feathers of the Osiris cult, the resulting diadem was referred to as the Atef crown.

According to the Hebrew Bible, Kings in Biblical Israel were crowned and anointed, most often by (or at the behest of) a prophet or high priest. In I Samuel 10:1, the prophet Samuel anoints Saul to be Israel's first king, though there is no record of his being crowned. However, on Saul's death, a crown that was on his head is presented to David II Samuel 1:10. Later, in I Samuel 16:13, Samuel anoints David to replace him - but again there is no reference to a crown at that point. In II Samuel 12:30, David is crowned with the Ammonite crown, after his conquest of Rabbah, the Ammonite capital. II Kings 9:1-6 tells of the anointing of Jehu as king of Israel. Esther 2:17 relates the crowning of Esther as consort of Ahasuerus, king of Persia. [5]

A detailed account of a coronation in ancient Judah is found in II Kings 11:12 and II Chronicles 23:11, in which the seven-year-old Jehoash is crowned in a coup against the usurper Athaliah. This ceremony took place in the doorway of the Temple in Jerusalem. The king was led to "his pillar", "as the manner was", where a crown was placed upon his head, and "the testimony" given to him, followed by anointing at the hands of the high priest and his sons. Afterwards, the people "clapped their hands" and shouted "God save the King" as trumpets blew, music played, and singers offered hymns of praise. All of these elements would find their way in some form or another into future European coronation rituals after the conversion of Europe to Christianity many centuries later, and all Christian coronation rites continue to borrow from these examples.

Plutarch wrote in his Life of King Artaxerxes that the Persian king was required to go to the ancient capital of Pasargadae for his coronation ceremony. Once there, he entered a temple "to a warlike goddess, whom one might liken to Artemis" (whose name is unknown today, nor can this temple be located), and there divested himself of his own robe, substituting the one worn by Cyrus I at his crowning. After this, he had to consume a "frail" of figs, eat turpentine and drink a cup of sour milk. Plutarch observed that "if they add any other rites, it is unknown to any but those that are present at them". [6]

The depiction of crowned heads on the obverse of coins becomes widespread from the 4th century onward. At first, these depict mainly deities, not kings, e.g. the Mother of Gods wearing the turreted crown (Rhea-Kybele is often depicted wearing the "turret crown", and is also given the title of Mater turrita by Ovid), Athena wearing a crowned helmet, or Zeus wearing a laurel wreath.

In the early 3rd century BC, the Seleucid rulers begin to depict their own portraits on their coins, typically wearing a headband or diadem.

The Book of Revelation in the New Testament makes extensive use of the crown motif, associating it with shared rulership for the saints in heaven (2:10, 3:11, 4:4) conquering (6:2) and ultimate rulership (14:14, 19:12). This suggests that the association was clearly understood in the Graeco-Roman world.

The original status of the Roman emperors was in contrast to the kings of Rome who were expelled in the early years of the city, paving the way for a republic. Therefore, the Emperors were traditionally acclaimed by the Senate or by a legion speaking for the armies as a whole, and were subsequently confirmed without any special ritual. The Eastern diadem was later introduced by Aurelian, [7] but did not truly become part of the imperator's regalia until the reign of Constantine. [8] Prior to this, Roman sovereigns wore the purple paludamentum, and sometimes a laurel wreath as emblems of their office. [8] Aurelian strengthened the position of Sol Invictus, whose corona radiata or "radiant crown" had become popular in depictions of emperors earlier in the 3rd century (Gordian III) with the development of the imperial cult,. [9] Emperor Diocletian (r. 285-305) greatly developed the ceremony surrounding the Roman Emperor; the quasi-republican ideals of Augustus' primus inter pares were abandoned for all but the Tetrarchs themselves. Diocletian took to wearing a gold crown and jewels, and forbade the use of purple cloth to all but the Emperors. [10]

Constantine the Great reverted to the diadem (while he still was depicted alongside Sol Invictus, he was no longer shown as Sol Invictus). Following the assumption of the diadem by Constantine, future Roman and Byzantine emperors continued to wear it as the supreme symbol of their authority. Although no specific coronation ceremony was observed at first, one gradually evolved over the next century. The emperor Julian was hoisted upon a shield and crowned with a gold necklace provided by one of his standard-bearers; [8] he later wore a jewel-studded diadem. Future emperors were crowned and acclaimed in a similar manner, until the momentous decision was taken to permit the Patriarch of Constantinople to physically place the crown on the emperor's head. Historians debate exactly when this first took place, but the precedent was clearly established by the reign of Leo II, who was crowned by the Patriarch Acacius in 473. This ritual included recitation of prayers by the Byzantine prelate over the crown, a further—and extremely vital—development in the liturgical ordo of crowning. After this event, according to the Catholic Encyclopedia, "the ecclesiastical element in the coronation ceremonial rapidly develop[ed]". [8]

The Byzantine coronation ritual, from at least 795 on, incorporated a partial clothing of the new emperor in various items of special clothing prior to his entrance to the church, following which he entered the cathedral and received the prostrations of the Senators and other patricians. The Patriarch then read a set of lengthy prayers, as the sovereign was invested first with the chlamys and then finally with the crown. Following this, the emperor received Holy Communion followed by further acts of homage. [8] [11] From the moment of his coronation, Byzantine emperor was regarded as holy; while the Patriarch was holding the crown over the emperor's head, the attending people repeatedly cried: Holy! [12]

In later centuries, after receiving their crown from the Patriarch, Byzantine emperors placed it upon their own head, symbolizing that their dominion came directly from God. [13] [14] Anointing was added to the ritual after the eleventh century, with the monarch receiving the Sign of the Cross on their forehead from the Patriarch. The purple chlamys also disappeared from the rite during this time, being replaced with the mandyas , or cope. [8]

The Byzantine coronation ceremony begins to influence the Barbarian kingdoms in the West with their Christianization. The Iron Crown of Lombardy is traced in legend to Constantine himself (but more likely dates to the 8th or 9th century). In Spain, the Visigothic king Sisenand was crowned in 631, and in 672, Wamba was the first occidental king to be anointed as well, by the archbishop of Toledo.

Two prayers for the coronation of Byzantine emperors are found in the Byzantine Archieratikon (Slavonic: Chinovnik). The second of these prayers is proceeded by the diaconal command: "Bow your heads to the Lord" and the assembly's response: "To you, O Lord." This pattern of two prayers corresponds to the ritual form found in the Byzantine liturgy for the ordinations of bishops, priests and deacons and also for major blessings, such as the Great Blessing of Waters on the Feast of the Theophany. In some texts, the first prayer is associated with the act of clothing the emperor in the chlamys and the second with the act of crowning him. [15] Although the Byzantine coronation ritual underwent various changes throughout the centuries, these two prayers are found consistently in every version. They also occur in the Russian ritual for the crowning of the Tsar, beginning with Ivan IV, and also in the ritual for the coronation of an emperor beginning with that of Catherine I.

In European Christianity, the divine right of kings, divine right, or God's mandation is a political and religious doctrine of political legitimacy of a monarchy. It stems from a specific metaphysical framework in which a monarch is, before birth, pre-ordained to inherit the crown. According to this theory of political legitimacy, the subjects of the crown have actively turned over the metaphysical selection of the king's soul – which will inhabit the body and rule them – to God. In this way, the "divine right" originates as a metaphysical act of humility and/or submission towards God. Divine right has been a key element of the legitimation of many absolute monarchies.

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, particularly in Commonwealth countries, as an abstract name for the monarchy itself, as distinct from the individual who inhabits it. A specific type of crown is employed in heraldry under strict rules. Indeed, some monarchies never had a physical crown, just a heraldic representation, as in the constitutional kingdom of Belgium, where no coronation ever took place; the royal installation is done by a solemn oath in parliament, wearing a military uniform: the King is not acknowledged as by divine right, but assumes the only hereditary public office in the service of the law; so he in turn will swear in all members of "his" federal government.

An imperial cult is a form of state religion in which an emperor or a dynasty of emperors are worshipped as demigods or deities. "Cult" here is used to mean "worship", not in the modern pejorative sense. The cult may be one of personality in the case of a newly arisen Euhemerus figure, or one of national identity or supranational identity in the case of a multi-ethnic state. A divine king is a monarch who is held in a special religious significance by his subjects, and serves as both head of state and a deity or head religious figure. This system of government combines theocracy with an absolute monarchy.

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of other items of regalia, marking the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power. Aside from the crowning, a coronation ceremony may comprise many other rituals such as the taking of special vows by the monarch, the investing and presentation of regalia to the monarch, and acts of homage by the new ruler's subjects and the performance of other ritual deeds of special significance to the particular nation. Western-style coronations have often included anointing the monarch with holy oil, or chrism as it is often called; the anointing ritual's religious significance follows examples found in the Bible. The monarch's consort may also be crowned, either simultaneously with the monarch or as a separate event.

The coronation of the British monarch is a ceremony in which the monarch of the United Kingdom is formally invested with regalia and crowned at Westminster Abbey. It corresponds to the coronations that formerly took place in other European monarchies, all of which have abandoned coronations in favour of inauguration or enthronement ceremonies.

The chlamys was a type of an ancient Greek cloak. By the time of the Byzantine Empire it was, although in a much larger form, part of the state costume of the emperor and high officials. It survived as such until at least the 12th century AD.

An enthronement is a ceremony of inauguration, involving a person—usually a monarch or religious leader—being formally seated for the first time upon their throne. Enthronements may also feature as part of a larger coronation rite.

The Coronation of the Hungarian monarch was a ceremony in which the king or queen of the Kingdom of Hungary was formally crowned and invested with regalia. It corresponded to the coronation ceremonies in other European monarchies. While in countries like France and England the king's reign began immediately upon the death of his predecessor, in Hungary the coronation was absolutely indispensable: if it were not properly executed, the Kingdom stayed "orphaned". All monarchs had to be crowned as King of Hungary in order to promulgate laws and exercise his royal prerogatives in the Kingdom of Hungary. Starting from the Golden Bull of 1222, all new Hungarian monarchs had to take a coronation oath, by which they had to agree to uphold the constitutional arrangements of the country, and to preserve the liberties of their subjects and the territorial integrity of the realm.

The Coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor was a ceremony in which the ruler of Western Europe's then-largest political entity received the Imperial Regalia at the hands of the Pope, symbolizing both the pope's right to crown Christian sovereigns and also the emperor's role as protector of the Roman Catholic Church. The Holy Roman Empresses were crowned as well.

The accession of the King of France to the royal throne was legitimized by a ceremony performed with the Crown of Charlemagne at Notre-Dame de Reims. In late medieval and early modern times, the new king did not need to be anointed in order to be recognized as French monarch but ascended upon the previous monarch's death with the proclamation "Le Roi est mort, vive le Roi!"

Coronations in Russia involved a highly developed religious ceremony in which the Emperor of Russia was crowned and invested with regalia, then anointed with chrism and formally blessed by the church to commence his reign. Although rulers of Muscovy had been crowned prior to the reign of Ivan III, their coronation rituals assumed overt Byzantine overtones as the result of the influence of Ivan's wife Sophia Paleologue, and the imperial ambitions of his grandson, Ivan IV. The modern coronation, introducing "Western European-style" elements, replaced the previous "crowning" ceremony and was first used for Catherine I in 1724. Since czarist Russia claimed to be the "Third Rome" and the replacement of Byzantium as the true Christian state, the Russian rite was designed to link its rulers and prerogatives to those of the so-called "Second Rome" (Constantinople).

Napoleon was crowned Emperor of the French on Sunday, December 2, 1804, at Notre-Dame de Paris in Paris. It marked "the instantiation of [the] modern empire" and was a "transparently masterminded piece of modern propaganda".

Bas-relief carvings in the ancient Egyptian temple of Deir el-Bahari depict events in the life of the pharaoh or monarch Hatshepsut of the Eighteenth Dynasty. They show the Egyptian gods, in particular Amun, presiding over her creation, and describe the ceremonies of her coronation. Their purpose was to confirm the legitimacy of her status as a woman pharaoh. Later rulers attempted to erase the inscriptions.

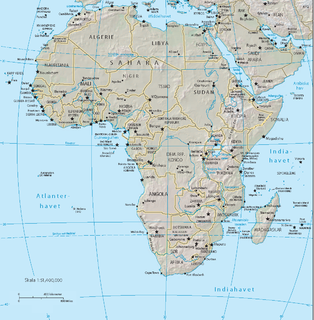

Coronations in Africa are held, or have been held, in or amongst the following countries, regions and peoples:

Coronations in Asia in the strict sense are and historically were rare, as only few monarchies, primarily in Western Asia, ever adopted the concept that the placement of a crown symbolised the monarch's investiture. Instead, most monarchies in Asia used a form of acclamation or enthronement ceremony, in which the monarch formally ascends to the throne, and may be presented with certain regalia, and may receive homage from his or her subjects. This article covers both coronations and enthronement.

Coronations in Europe were previously held in the monarchies of Europe. The United Kingdom is the only monarchy in Europe that still practices coronation. Current European monarchies have either replaced coronations with simpler ceremonies to mark an accession or have never practiced coronations. Most monarchies today only require a simple oath to be taken in the presence of the country's legislature.

A radiant or radiate crown, also known as a solar crown, sun crown, Eastern crown, or tyrant's crown, is a crown, wreath, diadem, or other headgear symbolizing the sun or more generally powers associated with the sun. Apart from the Ancient Egyptian form of a disc between two horns, it is shaped with a number of narrowing bands going outwards from the wearer's head, to represent the rays of the sun. These may be represented either as flat, on the same plane as the circlet of the crown, or rising at right angles to it.

The coronation of the Danish monarch was a religious ceremony in which the accession of the Danish monarch was marked by a coronation ceremony. It was held in various forms from 1170 to 1840, mostly in Lund Cathedral in Lund, St. Mary's Cathedral in Copenhagen and in the chapel of Frederiksborg Palace in Hillerød.

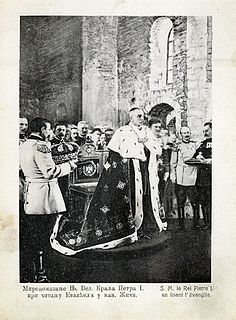

The accession of the Serbian monarch was legitimized by coronation ceremony. The coronation was carried out by church officials.

The coronation was the main symbolic act of accession to the throne of a Byzantine emperor, co-emperor, or empress. Founded on Roman traditions of election by the Senate or acclamation by the army, the ceremony evolved over time from a relatively simple, ad hoc affair to a complex ritual. In the 5th–6th centuries it became gradually standardized, with the new emperor appearing before the people and army at the Hippodrome of Constantinople, where he was crowned and acclaimed. During the same time, religious elements, notably the presence of the Patriarch of Constantinople, became prominent in what was previously a purely military or civilian ceremony. From the early 7th century on, the coronation ceremony usually took place in a church, chiefly the Hagia Sophia, the patriarchal cathedral of Constantinople. The ritual was apparently standardized by the end of the 8th century, and changed little afterwards. The main change was the addition of the emperor's unction in the early 13th century, likely under Western European influence, and the revival of the late antique practice of carrying the emperor on a shield in the 1250s.