This article needs additional citations for verification .(December 2020) |

In the medieval Roman Catholic church there were several Councils of Tours, that city being an old seat of Christianity, and considered fairly centrally located in France.

This article needs additional citations for verification .(December 2020) |

In the medieval Roman Catholic church there were several Councils of Tours, that city being an old seat of Christianity, and considered fairly centrally located in France.

The Council was called by Perpetuus, Bishop of Tours, to address the worldliness and profligacy of the Gallic clergy. [1] Athenius, Bishop of Rennes, took part in the First Council of Tours in AD 461. The last to sign the canons was Mansuetus, episcopus Brittanorum ("bishop of the Britons" [in Armorica]). [2] Also in attendance were Leo, Bishop of Bourges, and Victurius of Le Mans, [3] and three others.

The Breton bishops declined to attend, as Bishop Eufronius claimed authority over the Breton church. [4] Among those who did attend was Chaletricus of Chartres. [5]

At the Second, it was decreed that the sanctuary gates were to remain open so that the faithful might at any time go before the altar for prayer (canon IV); a married bishop should treat his wife as a sister (canon XII). No priest or monk was to share his bed with someone else; and monks were not to have single or double cells, but were to have a common dormitory in which two or three were to take turns in staying awake and reading to the rest (canon XIV). If a monk married or had familiarity with a woman, he was to be excommunicated from the church until he returned penitent to the monastery enclosure and thereafter underwent a period of penance (canon XV). No woman was to be allowed to enter the monastery enclosure, and if anyone saw a woman enter and did not immediately expel her, he was to be excommunicated (canon XVI). Married priests, deacons and subdeacons should have their wives sleep together with the maidservants, while they themselves slept apart, and if anyone of them were found to be sleeping with his wife, he was to be excommunicated for a year and reduced to the lay state (canon XIX). [6]

The council also noted that some Gallo-Roman customs of ancestor worship were still being observed. Canon XXII decreed that anyone known to be participating in these practices was barred from receiving communion and not allowed to enter a church. [7]

The bishops of the Kingdom of Paris were particularly concerned about the Merovingian practice of seizing ecclesiastical properties in outlying areas in order to fund their internecine wars. [8]

The Council proclaimed that the entire period between Christmas and Epiphany should be considered part of the celebration, creating what became known as the twelve days of Christmas, or Christmastide. [9]

A Council of Tours in 813 decided that priests should preach sermons in rusticam romanam linguam (rustic romance language) or Theodiscam (German), [10] a mention of Vulgar Latin understood by the people, as distinct from the classical Latin that the common people could no longer understand. [11] This was the first official recognition of an early French language distinct from Latin. [12]

This council was occasioned by controversy regarding the nature of the Eucharist. It was presided over by the papal legate Hildebrand, later Pope Gregory VII. Berengar of Tours wrote a profession of faith wherein he confessed that after consecration the bread and wine were truly the body and blood of Christ. [13]

Those men who marry their kinswomen, or those women who keep an unchaste correspondence with their kinsman, and refuse to leave them, or to do penance, shall be excluded from the community of the faithful, and turned out of the church (canon IX).

Shortly before the council, Geoffrey of Clairvaux met Pope Alexander in Paris to request the canonization of Geoffrey's predecessor, Bernard. The Pope deferred at the time due to the many like requests he had received. [14] At the council, Thomas Becket requested that Anselm of Canterbury, another Archbishop of Canterbury who had had difficulties with a king, be canonized. Although Alexander authorized Becket to hold a provincial council on the matter, upon his return to England, Becket seems not to have pursued the matter. [15] Among the decrees were those addressing simony, the sale of churches and ecclesiastical goods to laymen, and heretical sects spreading over southern France from Toulouse. [16] Canon IV forbid any priest to accept any gratuity for administering Last Rites or presiding at a burial. [17]

The First Council of the Lateran was the 9th ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church. It was convoked by Pope Callixtus II in December 1122, immediately after the Concordat of Worms. The council sought to bring an end to the practice of the conferring of ecclesiastical benefices by people who were laymen, free the election of bishops and abbots from secular influence, clarify the separation of spiritual and temporal affairs, re-establish the principle that spiritual authority resides solely in the Church and abolish the claim of the Holy Roman Emperor to influence papal elections.

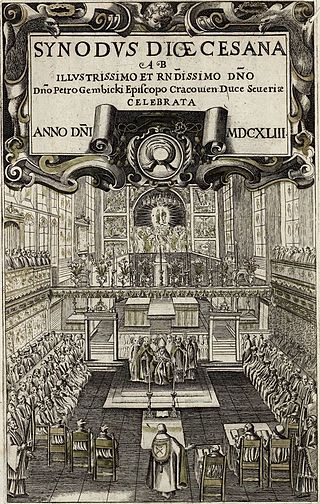

A synod is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word synod comes from the Greek: σύνοδος [ˈsinoðos] meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin word concilium meaning "council". Originally, synods were meetings of bishops, and the word is still used in that sense in Catholicism, Oriental Orthodoxy and Eastern Orthodoxy. In modern usage, the word often refers to the governing body of a particular church, whether its members are meeting or not. It is also sometimes used to refer to a church that is governed by a synod.

The Second Council of the Lateran was the tenth ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church. It was convened by Pope Innocent II in April 1139 and attended by close to a thousand clerics. Its immediate task was to neutralise the after-effects of the schism which had arisen after the death of Pope Honorius II in 1130 and the papal election that year that established Pietro Pierleoni as the antipope Anacletus II.

The Quinisext Council, i.e., the Fifth-Sixth Council, often called the Council in Trullo, Trullan Council, or the Penthekte Synod, was a church council held in 692 at Constantinople under Justinian II. It is known as the "Council in Trullo" because, like the Sixth Ecumenical Council, it was held in a domed hall in the Imperial Palace. Both the Fifth and the Sixth Ecumenical Councils had omitted to draw up disciplinary canons, and as this council was intended to complete both in this respect, it took the name of Quinisext. It was attended by 215 bishops, mostly from the Eastern Roman Empire. Basil of Gortyna in Crete belonged to the Roman patriarchate and called himself papal legate, though no evidence is extant of his right to use that title.

The Council of Epaone or Synod of Epaone was held in September 517 at Epaone in the Burgundian Kingdom.

The Councils of Carthage were church synods held during the 3rd, 4th, and 5th centuries in the city of Carthage in Africa. The most important of these are described below.

The Council of Agde was a regional synod held in September 506 at Agatha or Agde, on the Mediterranean coast east of Narbonne, in the Septimania region of the Visigothic Kingdom, with the permission of the Visigothic King Alaric II.

The First Council of Orléans was convoked by Clovis I, King of the Franks, in 511. Clovis called for this synod four years after his victory over the Visigoths under Alaric II at the Battle of Vouillé in 507. The council was attended by thirty-two bishops, including four metropolitans, from across Gaul, and together they passed thirty-one decrees. The bishops met at Orléans to reform the church and construct a strong relationship between the crown and the Catholic episcopate, the majority of the canons reflecting compromise between these two institutions.

Saint Prætextatus, also spelled Praetextatus, Pretextat(us), and known as Saint Prix, was the bishop of Rouen from 549 until his assassination in 586. He appears as a prominent character in Gregory of Tours’ Historia Francorum. This is the principal source from which information on his life can be drawn. He features in many of its most notable passages, including those pertaining to his trial in Paris and his rivalry with the Merovingian Queen Fredegund. The events of his life, as portrayed by Gregory of Tours, have been important in the development of modern understandings of various facets of Merovingian society, such as law, the rivalry between kings and bishops, church councils, and the power of queens.

Arles in the south of Roman Gaul hosted several councils or synods referred to as Concilium Arelatense in the history of the early Christian church.

The Fifth Council of Orléans assembled nine archbishops and forty-one bishops. Sacerdos of Lyon presided over this council. The presence of these bishops indicates both the wide spread of Christianity in Gaul by the sixth century, and the increased influence of the Merovingian kings.

Eufronius or Euphronius was the eighth Bishop of Tours; he served from 555 to 573, and was a near relative of Gregory of Tours.

Hilary was a medieval bishop of Chichester in England. English by birth, he studied canon law and worked in Rome as a papal clerk. During his time there, he became acquainted with a number of ecclesiastics, including the future Pope Adrian IV, and the writer John of Salisbury. In England, he served as a clerk for Henry of Blois, who was the bishop of Winchester and brother of King Stephen of England. After Hilary's unsuccessful nomination to become Archbishop of York, Pope Eugene III compensated him by promoting him to the bishopric of Chichester in 1147.

The Diocese of Anagni-Alatri is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or diocese of the Catholic Church in Lazio, Italy. It has existed in its current form since 1986. In that year the Diocese of Alatri was united to the historical Diocese of Anagni. The diocese is immediately exempt to the Holy See.

In the First Council of Braga, held in 561 in the city of Braga, eight bishops took part, and twenty-two decrees were promulgated. In a number of canons, the council took aim directly at doctrines of Priscillianism.

The Third Council of Braga was held in 675, during the primacy of Leodegisius, and in the reign of King Wamba. It was attended by eight bishops.

In the canon law of the Catholic Church, excommunication is a form of censure. In the formal sense of the term, excommunication includes being barred not only from the sacraments but also from the fellowship of Christian baptism. The principal and severest censure, excommunication presupposes guilt; and being the most serious penalty that the Catholic Church can inflict, it supposes a grave offense. The excommunicated person is considered by Catholic ecclesiastical authority as an exile from the Church, for a time at least.

The Council of Paris was a synod convoked by King Chlothar II in 614. It was a concilium mixtum, attended by both ecclesiastics and laymen from throughout the kingdom of the Franks. It was the first of three councils held by Chlothar. It helped secure his rule over the whole kingdom, which he only acquired in 613.