Berea College is a private liberal arts work college in Berea, Kentucky. Founded in 1855, Berea College was the first college in the Southern United States to be coeducational and racially integrated. The college provides a work-study grant that covers the remaining tuition fees after subtracting the total sum a student received from Pell Grant, other grants, and scholarships. Berea's primary service region is southern Appalachia but students come from more than 40 states in the United States and 70 other countries. Approximately one in three students identify as people of color.

Appalachia is a socio-economic region located in the central and southern sections of the Appalachian Mountains of the Eastern United States. It stretches from the western Catskill Mountains in the east end of the Southern Tier of New York state west and south into Pennsylvania, continuing on through the Blue Ridge Mountains into northern Georgia, and through the Great Smoky Mountains from North Carolina into Tennessee and northern Alabama. In 2020, the region was home to an estimated 26.1 million people, of whom roughly 80% were white.

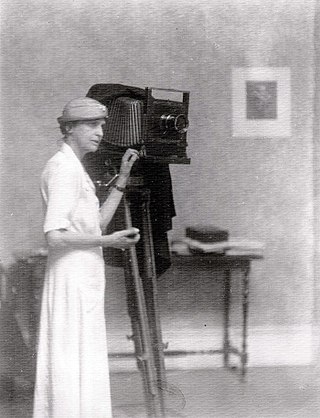

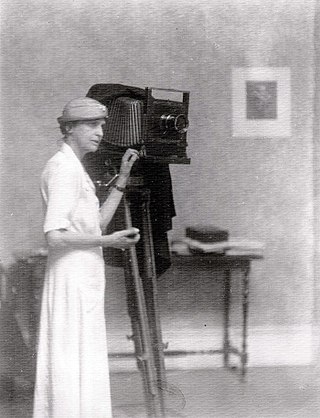

Doris Ulmann was an American photographer, best known for her portraits of the people of Appalachia, particularly craftsmen and musicians, made between 1928 and 1934.

Appalachian music is the music of the region of Appalachia in the Eastern United States. Traditional Appalachian music is derived from various influences, including the ballads, hymns and fiddle music of the British Isles, the African music and blues of early African Americans, and to a lesser extent the music of Continental Europe.

Gurney Norman is an American writer documentarian, and professor.

In the United States, the Hillbilly Highway is the out-migration of Appalachians from the Appalachian Highlands region to industrial cities in northern, midwestern, and western states, primarily in the years following World War II in search of better-paying industrial jobs and higher standards of living. Many of these migrants were formerly employed in the coal mining industry, which started to decline in 1940s. The word hillbilly refers to a negative stereotype of people from Appalachia. The term hillbilly is considered to be a modern term because it showed up in the early 1900s. Though the word is Scottish in origin, but doesn't derive from dialect. In Scotland, the term "hill-folk" referred to people who preferred isolation from the greater society and the term "billy" referred to someone being a "companion" or "comrade". The Hillbilly Highway was a parallel to the better-known Great Migration of African-Americans from the south.

Appalachian studies is the area studies field concerned with the Appalachian region of the United States.

Urban Appalachians are people from Appalachia who are living in metropolitan areas outside of the region. Because migration has been occurring for decades, most are not first generation migrants from the region but are long-term city dwellers. People have been migrating from Appalachia to cities outside the region ever since many of these cities were founded. It was not until the period following World War II, however, that large-scale migration to urban areas became common due to the decline of coal mining and the increase in industrial jobs available in the Midwest and Northeast. The migration of Appalachians is often known as the Hillbilly Highway.

John B. Stephenson was a sociologist and scholar of Appalachia, a founder of the Appalachian Studies Conference, and president of Berea College from 1984 to 1994.

Appalachian Volunteers (AV) was a non-profit organization engaged in community development projects in central Appalachia that evolved into a controversial community organizing network, with a reputation that went "from self-help to sedition" as its staff developed from "reformers to radicals," teaching things from Marx, Lenin and Mao, in the words of one historian, in the brief period between 1964 and 1970 during the War on Poverty.

David Walls is an activist and academic who has made significant contributions to Appalachian studies and to the popular understanding of social movements. He is professor emeritus of sociology at Sonoma State University (SSU) in California, where he was dean of extended education from 1984 to 2000.

Settlement schools are social reform institutions established in rural Appalachia in the early 20th century with the purpose of educating mountain children and improving their isolated rural communities.

Our Southern Highlanders: A Narrative of Adventure in the Southern Appalachians and a Study of Life Among the Mountaineers is a book written by American author Horace Kephart (1862–1931), first published in 1913 and revised in 1922. Inspired by the years Kephart spent among the inhabitants of the remote Hazel Creek region of the Great Smoky Mountains, the book provides one of the earliest realistic portrayals of life in the rural Appalachian Mountains and one of the first serious analyses of Appalachian culture. While modern historians and writers have criticized Our Southern Highlanders for focusing too much on sensationalistic aspects of mountain culture, the book was an important departure from the previous century's local color writings and their negative distortions of mountain people.

"Yew Piney Mountain" is part of the canonical Appalachian music tradition which has been highly influential in American fiddle tradition generally, including its old time fiddle and bluegrass fiddle branches. According to Alan Jabbour at the Digital Library of Appalachia, the tune was called "Blackberry Blossom" until that title was taken over by a different tune. The earlier "Blackberry Blossom", as played by Sanford Kelly from Morgan County, is now represented by the tune "Yew Piney Mountain".

The Appalachian region and its people have historically been stereotyped by observers, with the basic perceptions of Appalachians painting them as backwards, rural, and anti-progressive. These widespread, limiting views of Appalachia and its people began to develop in the post-Civil War; Those who "discovered" Appalachia found it to be a very strange environment, and depicted its "otherness" in their writing. These depictions have persisted and are still present in common understandings of Appalachia today, with a particular increase of stereotypical imagery during the late 1950s and early 1960s in sitcoms. Common Appalachian stereotypes include those concerning economics, appearance, and the caricature of the "hillbilly."

Jim Wayne Miller was an American poet and educator who had a major influence on literature in the Appalachian region.

Helen Matthews Lewis was an American sociologist, historian, and activist who specialized in Appalachia and women's rights. She was noted for developing an interpretation of Appalachia as an internal United States colony, as well as designing the first academic programs for Appalachian studies. She also specialized in Appalachian oral history, collecting and preserving the experiences of Appalachian working-class women in their own words. She is known as the "grandmother of Appalachian Studies" as her work has influenced a generation of scholars who focus on Appalachia.

Helen Dingman was an American academic and social worker who was one of the central figures in the Progressive and New Deal eras to bring social and economic reform to Appalachia. After teaching in Massachusetts for five years from 1912 to 1917, Dingman moved to Kentucky to establish the Smith Community Life School under the auspices of the United Presbyterian Church. Serving as principal and directing six other schools in Harlan County, Kentucky, she provided both education and social services to the community until 1922. After a two year placement as an assistant superintendent for the mission board in New York, she was hired as a teacher in the Sociology Department at Berea College. She taught social work courses and trained teachers for the rural schools in the region until 1952. In addition, she served as Executive Secretary of the Conference of Southern Mountain Workers, establishing the professional basis for social workers. The first comprehensive economic and social survey of the Southern Appalachias was spearheaded by Dingman.

The Metro Detroit region of Michigan is home to a significant Appalachian population, one of the largest populations of Urban Appalachians in the United States. The most common state of origin for Appalachian people in Detroit is Kentucky, while many others came from Tennessee, West Virginia, Virginia, Ohio, and elsewhere in the Appalachia region. The Appalachian population has historically been centered in the Detroit neighborhoods of Brightmoor, Springwells, Corktown and North Corktown, as well as the Detroit suburbs of Hazel Park, Ypsilanti, Taylor, and Warren. Beginning after World War I, Appalachian people moved to Detroit in large numbers seeking jobs. Between 1940 and 1970, approximately 3.2 million Appalachian and Southern migrants settled in the Midwest, particularly in large cities such as Detroit and Chicago. This massive influx of rural Appalachian people into Northern and Midwestern cities has been called the "Hillbilly Highway". The culture of Metro Detroit has been significantly influenced by the culture, music, and politics of Appalachia. The majority of people of Appalachian heritage in Metro Detroit are Christian and either white or black, though Appalachian people can be of any race, ethnicity, or religion.

Loyal Jones was an American folklorist, Appalachian culture scholar, and writer.