Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ "O.S. 21-1327". Archived from the original on 2013-09-27. only applies in the schools.

Related Research Articles

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the labour movement that, through industrial unionism, seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes, with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of production and the economy at large through social ownership. Developed in French labor unions during the late 19th century, syndicalist movements were most predominant amongst the socialist movement during the interwar period that preceded the outbreak of World War II.

Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court concerning enforcement of the Espionage Act of 1917 during World War I. A unanimous Supreme Court, in an opinion by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., concluded that Charles Schenck, who distributed flyers to draft-age men urging resistance to induction, could be convicted of an attempt to obstruct the draft, a criminal offense. The First Amendment did not protect Schenck from prosecution, even though, "in many places and in ordinary times, Schenck, in saying all that was said in the circular, would have been within his constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done." In this case, Holmes said, "the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent." Therefore, Schenck could be punished.

Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969), is a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court interpreting the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Court held that the government cannot punish inflammatory speech unless that speech is "directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action". Specifically, the Court struck down Ohio's criminal syndicalism statute, because that statute broadly prohibited the mere advocacy of violence. In the process, Whitney v. California (1927) was explicitly overruled, and Schenck v. United States (1919), Abrams v. United States (1919), Gitlow v. New York (1925), and Dennis v. United States (1951) were overturned.

Industrial unionism is a trade union organising method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union, regardless of skill or trade, thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in bargaining and in strike situations.

William Dudley Haywood, nicknamed "Big Bill", was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of America. During the first two decades of the 20th century, Haywood was involved in several important labor battles, including the Colorado Labor Wars, the Lawrence Textile Strike, and other textile strikes in Massachusetts and New Jersey.

Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357 (1927), was a United States Supreme Court decision upholding the conviction of an individual who had engaged in speech that raised a clear and present danger to society. While the majority of the Supreme Court Justices voted to uphold the conviction, the ruling has become an important free speech precedent due a concurring opinion by Justice Louis Brandeis recommending new perspectives on criticism of the government by citizens. The ruling was explicitly overruled by Brandenburg v. Ohio in 1969.

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958), was a U.S. Supreme Court case addressing the State of California's refusal to grant to ACLU lawyer Lawrence Speiser, a veteran of World War II, a tax exemption because that person refused to sign a loyalty oath as required by a California law enacted in 1954. The court reversed a lower court ruling that the loyalty oath provision did not violate the appellants' First Amendment rights.

"Imminent lawless action" is one of several legal standards American courts use to determine whether certain speech is protected under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. The standard was first established in 1969 in the United States Supreme Court case Brandenburg v. Ohio.

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 (1931), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States in which the Court held, 7–2, that a California statute banning red flags was unconstitutional because it violated the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution. In the case, Yetta Stromberg was convicted for displaying a red flag daily in the youth camp for children at which she worked, and was charged in accordance with California law. Chief Justice Charles Hughes wrote for the seven-justice majority that the California statute was unconstitutional, and therefore Stromberg's conviction could not stand.

De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353 (1937), was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Fourteenth Amendment's due process clause applies the First Amendment right of freedom of assembly to the individual U.S. states. The Court found that Dirk De Jonge had the right to speak at a peaceful public meeting held by the Communist Party, even though the party generally advocated an industrial or political change in revolution. However, in the 1950s with the fear of communism on the rise, the Court ruled in Dennis v. United States (1951) that Eugene Dennis, who was the leader of the Communist Party, violated the Smith Act by advocating the forcible overthrow of the United States government.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was an American labor leader, activist, and feminist who played a leading role in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Flynn was a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union and a visible proponent of women's rights, birth control, and women's suffrage. She joined the Communist Party USA in 1936 and late in life, in 1961, became its chairwoman. She died during a visit to the Soviet Union, where she was accorded a state funeral with processions in Red Square attended by over 25,000 people.

Free speech fights are struggles over free speech, and especially those struggles which involved the Industrial Workers of the World and their attempts to gain awareness for labor issues by organizing workers and urging them to use their collective voice. During the World War I period in the United States, the IWW members, engaged in free speech fights over labor issues which were closely connected to the developing industrial world as well as the Socialist Party. The Wobblies, along with other radical groups, were often met with opposition from local governments and especially business leaders, in their free speech fights.

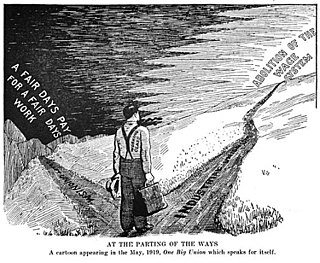

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is a union of wage workers which was formed in Chicago in 1905 by militant unionists and their supporters due to anger over the conservatism, philosophy, and craft-based structure of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Throughout the early part of the 20th century, the philosophy and tactics of the IWW were frequently in direct conflict with those of the AFL concerning the best ways to organize workers, and how to best improve the society in which they toiled. The AFL had one guiding principle—"pure and simple trade unionism", often summarized with the slogan "a fair day's pay for a fair day's work." The IWW embraced two guiding principles, fighting like the AFL for better wages, hours, and conditions, but also promoting an eventual, permanent solution to the problems of strikes, injunctions, bull pens, and union scabbing.

Charlotte Anita Whitney, best known as "Anita Whitney", was an American women's rights activist, political activist, suffragist, and early Communist Labor Party of America and Communist Party USA organizer in California.

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) is a union of wage workers which was formed in Chicago in 1905. The IWW experienced a number of divisions and splits during its early history.

The California Criminal Syndicalism Act was a law of California in 1919 under Governor William Stephens criminalizing syndicalism. It was enacted on April 30, 1919, and repealed in 1991. The law stated that "any person who was a member of any organization that advocated criminal syndicalism was guilty of a felony and punishable by up to 14 years in the state prison. The law is significant, and controversial, because it made certain beliefs illegal. A person did not have to commit any overt act. Simple advocacy of a certain belief or membership in a group that advocated syndicalism was enough to secure a conviction".

Fiske v. Kansas, 274 U.S. 380 (1927), was a United States Supreme Court Case that was first argued May 3, 1926 and finally decided May 16, 1927.

Nicolaas Steelink was a Dutch American labor activist who was a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), an international industrial union, and an important figure in the creation of the California Soccer League, which resulted in his induction into the United States Soccer Hall of Fame. During his time as a member of the IWW, due to his involvement with the union and radical ideals, he was convicted of criminal syndicalism and sentenced to prison in 1920.

The 1923 San Pedro maritime strike was, at the time, the biggest challenge to the dominance of the open shop culture of Los Angeles, California until the rise of the Congress of Industrial Organizations in the 1930s.

The Goldfield, Nevada labor troubles of 1906–1907 were a series of strikes and a lockout which pitted gold miners and other laborers, represented by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM) and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), against mine owners and businessmen.

References

- ↑ "Criminal Syndicalism Law & Legal Definition". US Legal, Inc.

- ↑ White, Ahmed A. "The Crime of Economic Radicalism: Criminal Syndicalism Laws and the Industrial Workers of the World, 1917–1927." Oregon Law Review 85, no. 3 (2006): 652. Accessed November 24, 2014. https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/5046/853white.pdf?sequence=1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Anti-Radical Agitation". CQ Press. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- ↑ White, p. 652.

- 1 2 3 Sims, Robert, C (1974). "Idaho's Criminal Syndicalism Act: One States Response to Radical Labor". Labor History. 15 (4): 511–527. doi:10.1080/00236567408584310.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 White, p. 650.

- 1 2 3 White, p. 687.

- 1 2 White, p. 688.

- ↑ Whitten, Woodrow C. "Criminal Syndicalism and the Law in California: 1919-1927."Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 59, no. 2 (1969): 15. Accessed November 25, 2014. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1006021.

- ↑ Blasi, Vincent. "The First Amendment and the Ideal of Civic Courage: The Brandeis Opinion in Whitney v. California." William and Mary Law Review 29, no. 4 (1988): 655. Accessed November 24, 2014. http://www.lexisnexis.com/lnacui2api/api/version1/getDocCui?lni=3S3V-3SV0-00CW-G2NH&csi=7413,270077&hl=t&hv=t&hnsd=f&hns=t&hgn=t&oc=00240&perma=true.

- ↑ White, p. 696.

- ↑ White, p. 697.

- ↑ White, p. 698.

- 1 2 3 Whitten, p. 13.

- ↑ White, p. 700.

- 1 2 Cortner, Richard C. (Spring 1981). "The Wobblies and Fiske v. Kansas: Victory Amidst Disintegration" (PDF). Kansas History . 4 (1). Kansas Historical Society: 30–38. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Franklin, F. G. (1920). "Anti-Syndicalist Legislation". American Political Science Review. 14 (2): 291–298. doi:10.2307/1943826. ISSN 0003-0554. JSTOR 1943826.

- 1 2 Urofsky, Melvin, I. "Charlotte Anita Whitney, Whitney v. California: Free Speech for Radicals". SAGE Publications. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Savage, David, G. "Freedom of Political Association". SAGE Publications. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Savage, David G. "Freedom of Speech". SAGE Publications. Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- 1 2 Sims, p. 512.

- ↑ White, p. 658.

- ↑ Goldstein, Robert Justin. Political Repression in Modern America from 1870 to 1976. Urbana: University of Illinois Press (2001): 128.

- ↑ Sims, p. 514.

- ↑ Sims, p. 525.

- ↑ Sims, p. 526.

- ↑ Sims, p. 527.

- 1 2 Blasi, p. 655.

- ↑ Whitten, p. 20.

- ↑ Whitten, p. 14.

- ↑ Whitten, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Whitten, p. 18.

- ↑ Whitten, p. 19.

- ↑ Whitten, p. 15.

- ↑ Whitten, p. 22.

- 1 2 Whitten, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Whitten, p. 25.

- ↑ "Brandenburg v. Ohio".

- ↑ Russel-Brown, Katheryn (February 3, 2015). Criminal Law. SAGE Publications. p. 29. ISBN 9781412977890.

- ↑ "California Education Code § 44932(a)(2)". California Office of Legislative Counsel. Archived from the original on 2014-03-31. Retrieved 2021-06-14.

- ↑ "K.S.A. 22-3101".

- ↑ "M.C. 185.06".