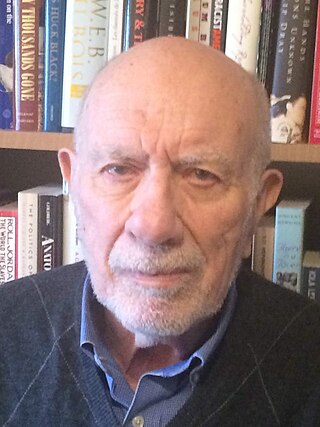

Crispin Sartwell | |

|---|---|

| Born | June 20, 1958 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Relatives | Herman Bernstein (great-grandfather) |

| Academic background | |

| Education | University of Maryland, College Park (BA) Johns Hopkins University (MA) University of Virginia (PhD) |

| Doctoral advisor | Richard Rorty |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | Philosophy Communication Political science |

| Institutions | Dickinson College Vanderbilt University University of Alabama Maryland Institute College of Art Millersville University of Pennsylvania |

Crispin Gallagher Sartwell (born June 20,1958) [1] is an American academic,philosopher,and journalist who was a faculty member of the philosophy department at Dickinson College in Carlisle,Pennsylvania until he retired in 2023. [2] He has taught philosophy,communication,and political science at Vanderbilt University,University of Alabama,Millersville University of Pennsylvania,the Maryland Institute College of Art,and Dickinson College. [3]

Born in Washington,D.C.,Sartwell is the son of Franklin Gallagher Sartwell,a reporter,editor,and photographer. His grandfather,also Franklin Gallagher Sartwell,was a columnist and editorial page editor at the Washington Times-Herald . His great-grandfather,Herman Bernstein broke the story of a secret correspondence between Kaiser Wilhelm and Nicholas II of Russia during World War I in The New York Times . [4] Sartwell worked as a freelance rock critic for publications,including Record and Melody Maker . [5]

His mother,Joyce Abell,and stepfather,Richard Abell,were teachers in Montgomery County,Maryland and organic vegetable farmers in Rappahannock County,Virginia.

Sartwell received a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Maryland,College Park,a Master of Arts from Johns Hopkins University and a PhD from the University of Virginia,where his dissertation supervisor was Richard Rorty. Sartwell wrote his dissertation on art and articulation,discussing pictorial representation in John Dewey,Martin Heidegger,Nelson Goodman,and Hans-Georg Gadamer.

A journalist since he was 20,Sartwell's syndicated column,distributed by Creators Syndicate,appeared in numerous newspapers through the 1990s and 2000s,including The Philadelphia Inquirer and Los Angeles Times . He has continued to write for the popular press,with work appearing in The New York Times as a contributing writer to the Times's philosophy section,The Stone. He has been published in The Atlantic , Harper's Bazaar , The Washington Post , All Things Considered and other venues. He has appeared on Washington Journal ,discussing political philosophy and ethics. Sartwell remains actively involved in music criticism,including writing a country music column for the New York Press .

Sartwell is a regular contributor to the webzine Splice Today . [6]

From 1989 through 1993,Sartwell was an Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at Vanderbilt University. From 1995 to 1996,Sartwell was an Annenberg Scholar in the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania.

Sartwell is best known as a political philosopher,with significant interests in analytic philosophy,aesthetics,and epistemology. As a political philosopher,he has been an advocate of anarchism and individual rights as opposed to the rights of the state. In his 2008 work,Against the State:An Introduction to Anarchist Political Philosophy, he refuted the traditional justifications for the state from Hobbes through Nozick. This was followed by his 2010 work,Political Aesthetics, in which he evaluated various systems based on the assumption that political systems are in part aesthetic systems.

Sartwell's interest in language as a system and its constraints and problems has been a constant in his career. Perhaps his clearest expression of this was in his 2000 publication,End of Story:Toward an Annihilation of Language and History, which posited an academic obsession with language qua language and narrative at the expense of a better conceptual and open dialogue.

As a philosopher of aesthetics as well as of language,Sartwell has seen the issues of beauty as being a constant in the search for meaning. His 2014 book How to Escape:Magic,Madness,Beauty and Cynicism,looked at a wide variety of artistic expressions and experiences from an aesthetics perspective. This followed his previous work,2004's Six Names of Beauty,in which he used different words for beauty in a variety of languages including Greek,Sanskrit,Japanese,and Navajo as a gateway to understanding the cultural diversity and similarities between ideas and manifestations of beauty. [7] [8] Later books include Entanglements:A System of Philosophy (2017) and Beauty:A Quick Immersion (2022).

On March 3,2016,Sartwell was placed on leave from his faculty position at Dickinson College in response to posts on his blog in which he accused other philosophy professors of plagiarism. [9] According to Sartwell,the action is related to a video,embedded in the blog post,of Miranda Lambert singing "Time to Get a Gun." [10] Additional problematic material was found on his blog,but given little to no mind by the college's administration. [11] In September,2016, The Dickinsonian reported that Sartwell had returned to his position and would resume teaching in the spring of 2017. [12]

In addition to his books,Sartwell has published more than 40 articles in academic journals such as the British Journal of Aesthetics,Philosophy Today,and American Philosophical Quarterly.

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is against all forms of authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state with stateless societies and voluntary free associations. As a historically left-wing movement, this reading of anarchism is placed on the farthest left of the political spectrum, usually described as the libertarian wing of the socialist movement.

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions, and ideological systems. Although usually contrasted with social anarchism, both individualist and social anarchism have influenced each other. Mutualism, an economic theory sometimes considered a synthesis of communism, market economy and property, has been considered individualist anarchism and other times part of social anarchism. Many anarcho-communists regard themselves as radical individualists, seeing anarcho-communism as the best social system for the realization of individual freedom. Some anarcho-capitalists claim anarcho-capitalism is part of the individualist anarchist tradition, while others disagree and claim individualist anarchism is only part of the socialist movement and part of the libertarian socialist tradition. Economically, while European individualist anarchists are pluralists who advocate anarchism without adjectives and synthesis anarchism, ranging from anarcho-communist to mutualist economic types, most American individualist anarchists of the 19th century advocated mutualism, a libertarian socialist form of market socialism, or a free-market socialist form of classical economics. Individualist anarchists are opposed to property that violates the entitlement theory of justice, that is, gives privilege due to unjust acquisition or exchange, and thus is exploitative, seeking to "destroy the tyranny of capital,—that is, of property" by mutual credit.

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and advocating that the interests of the individual should gain precedence over the state or a social group, while opposing external interference upon one's own interests by society or institutions such as the government. Individualism makes the individual its focus, and so starts "with the fundamental premise that the human individual is of primary importance in the struggle for liberation".

CrimethInc., also known as CWC, which stands for either "CrimethInc. Ex-Workers Collective" or "CrimethInc Ex-Workers Ex-Collective", is a decentralized anarchist collective of autonomous cells. CrimethInc. emerged in the mid-1990s, initially as the hardcore zine Inside Front, and began operating as a collective in 1996. It has since published widely read articles and zines for the anarchist movement and distributed posters and books of its own publication.

Robert Paul Wolff is an American political philosopher and professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

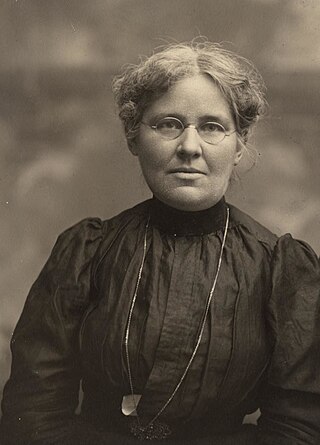

Voltairine de Cleyre was an American anarchist known for being a prolific writer and speaker who opposed capitalism, marriage, and the state, as well as the domination of religion over sexuality and over women's lives, all of which she saw as interconnected. She is often characterized as a major early feminist because of her views.

Anarchists have employed certain symbols for their cause, including most prominently the circle-A and the black flag. Anarchist cultural symbols have been prevalent in popular culture since around the turn of the 21st century, concurrent with the anti-globalization movement. The punk subculture has also had a close association with anarchist symbolism.

Anarchists have traditionally been skeptical of or vehemently opposed to organized religion. Nevertheless, some anarchists have provided religious interpretations and approaches to anarchism, including the idea that the glorification of the state is a form of sinful idolatry.

Mutualism is an anarchist school of thought and economic theory that advocates for workers' control of the means of production, a market economy made up of individual artisans and workers' cooperatives, and occupation and use property rights. As proponents of the labour theory of value and labour theory of property, mutualists oppose all forms of economic rent, profit and non-nominal interest, which they see as relying on the exploitation of labour. Mutualists seek to construct an economy without capital accumulation or concentration of land ownership. They also encourage the establishment of workers' self-management, which they propose could be supported through the issuance of mutual credit by mutual banks, with the aim of creating a federal society.

Adin Ballou was an American proponent of Christian nonresistance, Christian anarchism, and Christian socialism. He was also an abolitionist and the founder of the Hopedale Community.

Individualist anarchism in the United States was strongly influenced by Benjamin Tucker, Josiah Warren, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Lysander Spooner, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Max Stirner, Herbert Spencer and Henry David Thoreau. Other important individualist anarchists in the United States were Stephen Pearl Andrews, William Batchelder Greene, Ezra Heywood, M. E. Lazarus, John Beverley Robinson, James L. Walker, Joseph Labadie, Steven Byington and Laurance Labadie.

Todd Gifford May is a political philosopher who writes on topics of anarchism, poststructuralism, and post-structuralist anarchism. More recently he has published books on existentialism and moral philosophy. He is currently a professor of philosophy at Warren Wilson College.

The relation between anarchism and Friedrich Nietzsche has been ambiguous. Even though Nietzsche criticized anarchists, his thought proved influential for many of them. As such "[t]here were many things that drew anarchists to Nietzsche: his hatred of the state; his disgust for the mindless social behavior of 'herds'; his anti-Christianity; his distrust of the effect of both the market and the State on cultural production; his desire for an 'übermensch'—that is, for a new human who was to be neither master nor slave".

Everyday Aesthetics is a recent subfield of philosophical aesthetics focusing on everyday events, settings and activities in which the faculty of sensibility is saliently at stake. Alexander Baumgarten established Aesthetics as a discipline and defined it as scientia cognitionis sensitivae, the science of sensory knowledge, in his foundational work Aesthetica (1750). This field has been dedicated since then to the clarification of fine arts, beauty and taste only marginally referring to the aesthetics in design, crafts, urban environments and social practice until the emergence of everyday aesthetics during the ‘90s. As other subfields like environmental aesthetics or the aesthetics of nature, everyday aesthetics also attempts to countervail aesthetics' almost exclusive focus on the philosophy of art.

Market socialism is a type of economic system involving social ownership of the means of production within the framework of a market economy. Various models for such a system exist, usually involving cooperative enterprises and sometimes a mix that includes public or private enterprises. In contrast to the majority of historic socialist economies, which have substituted the market mechanism for some form of economic planning, market socialists wish to retain the use of supply and demand signals to guide the allocation of capital goods and the means of production. Under such a system, depending on whether socially owned firms are state-owned or operated as worker cooperatives, profits may variously be used to directly remunerate employees, accrue to society at large as the source of public finance, or be distributed amongst the population in a social dividend.

Adelaide De Claire Thayer (1864–1945) was an American schoolteacher and writer. Born into extreme poverty in Michigan, she and her younger sister Voltairine developed a love of reading and writing at an early age. After Adelaide fell ill, Voltairine was sent away to be educated in a convent, but the two kept in touch through letters. They continued to exchange correspondence with each other into adulthood, with Voltairine telling Adelaide of her work as a tutor and public speaker, as well as her romantic partners, although the two disagreed on politics and rarely spoke on the matter. Although Adelaide herself had wanted to become a journalist, her mother pressured her into work as a schoolteacher. She later converted to Baptist denomination and married two working class men, which her mother disliked. After Voltairine's death, Adelaide became a key primary source in her life and collector of her works, supplying Joseph Ishill and Agnes Inglis with many letters, which are today in the respective collections of Harvard University and the University of Michigan.

James B. Elliott (1849–1931) was an American freethinker. Through his involvement with a number of freethinking organizations and publications, he met the anarchist Voltairine de Cleyre, with whom he had a brief romantic relationship and fathered a child, Harry. He spent the 1890s raising his son, working as a carpenter and collecting memorabilia of his idol Thomas Paine. By the turn of the 20th century, he succombed to a mental disorder and became estranged from his family, leaving his son and losing contact with de Cleyre.

Harry de Cleyre (1890–1974) was and American house painter and writer. The son of Voltairine de Cleyre and James B. Elliott, he was abandoned by his mother and neglected by his father during his childhood. He struggled to apply himself in his education and was forced to start work at the age of 10. After his mother's death, he devoted himself to studying her work and preserving her memory; he became a key primary source on her life, writing several letters about her to Joseph Ishill and Agnes Inglis.

Audio/video media