Marcus Opellius Macrinus was Roman emperor from April 217 to June 218, reigning jointly with his young son Diadumenianus. As a member of the equestrian class, he became the first emperor who did not hail from the senatorial class and also the first emperor who never visited Rome during his reign. Before becoming emperor, Macrinus served under Emperor Caracalla as a praetorian prefect and dealt with Rome's civil affairs. He later conspired against Caracalla and had him murdered in a bid to protect his own life, succeeding him as emperor.

AD 97 (XCVII) was a common year starting on Sunday of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Augustus and Rufus. The denomination AD 97 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Sextus Varius Marcellus was a Roman aristocrat and politician from the province of Syria. He was father of the emperor Elagabalus.

Sextus Julius Frontinus was a prominent Roman civil engineer, author, soldier and senator of the late 1st century AD. He was a successful general under Domitian, commanding forces in Roman Britain, and on the Rhine and Danube frontiers. A novus homo, he was consul three times. Frontinus ably discharged several important administrative duties for Nerva and Trajan. However, he is best known to the post-Classical world as an author of technical treatises, especially De aquaeductu, dealing with the aqueducts of Rome.

Virius Lupus was a Roman soldier and politician of the late 2nd and early 3rd century.

The Battle of Lugdunum, also called the Battle of Lyon, was fought on 19 February 197 at Lugdunum, between the armies of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus and of the Roman usurper Clodius Albinus. Severus' victory finally established him as the sole emperor of the Roman Empire following the Year of the Five Emperors and immediate aftermath.

Gellius Maximus was a Roman usurper, who, in 219 AD, revolted against Emperor Elagabalus. His rebellion was swiftly crushed, and he himself was executed.

The Romans constructed aqueducts throughout their Republic and later Empire, to bring water from outside sources into cities and towns. Aqueduct water supplied public baths, latrines, fountains, and private households; it also supported mining operations, milling, farms, and gardens.

Lucius Marius Maximus Perpetuus Aurelianus was a Roman biographer, writing in Latin, who in the early decades of the 3rd century AD wrote a series of biographies of twelve Emperors, imitating and continuing Suetonius. Marius's work is lost, but it was still being read in the late 4th century and was used as a source by writers of that era, notably the author of the Historia Augusta. The nature and reliability of Marius's work, and the extent to which the earlier part of the HA draws upon it, are two vexed questions among the many problems that the HA continues to pose for students of Roman history and literature.

In Ancient Rome, the Aqua Alsietina was the earlier of the two western Roman aqueducts, erected sometime around 2 BC, during the reign of emperor Augustus. It was the only water supply for the Transtiberine region, on the right bank of the river Tiber until the Aqua Traiana was built.

Lucius Valerius Messalla Thrasea Priscus was a Roman senator active during the reigns of Commodus and Septimus Severus.

Pomponius Bassus [...]stus was a Roman Senator of Anatolian descent who lived in the Roman Empire.

Gaius Octavius Appius Suetrius Sabinus was a Roman senator and military officer who was appointed consul twice, firstly in AD 214, and secondly in AD 240.

Gaius Domitius Dexter was a Roman senator who was appointed consul twice: firstly as suffect consul prior to AD 183, and secondly as ordinary consul in AD 196 with Lucius Valerius Messalla Thrasea Priscus as his colleague.

Gaius Pomponius Bassus Terentianus was a Roman military officer and senator.

Gaius Caesonius Macer Rufinianus was a Roman military officer and senator who was appointed suffect consul in around AD 197 or 198. He was the first member of gens Caesonia to hold a consulship.

Lucius Caesonius Lucillus Macer Rufinianus was a Roman military officer and senator who was appointed suffect consul probably between AD 225 and 229. Much of what we know about him comes from an inscription found on the base of a statute near Tivoli.

In Imperial Rome, Cura Annonae was the import and distribution of grain to the residents of the cities of Rome and, after its foundation, Constantinople. The term was used in honour of the goddess Annona. The city of Rome imported all the grain consumed by its population, estimated to number 1,000,000 by the 2nd century AD. This included recipients of the grain dole or corn dole, a government program which gave out subsidized grain, then free grain, and later bread, to about 200,000 of Rome's adult male citizens. Rome's grain subsidies were originally ad hoc emergency measures taken to import cheap grain from trading partners and allies at times of scarcity, to help feed growing numbers of indebted and dispossessed citizen-farmers. By the end of the Republic, grain subsidies and doles had become permanent, uniquely Roman institutions. The grain dole was reluctantly adopted by Augustus and later emperors as a free monthly issue to those who qualified to receive it. In 22 AD, Augustus' successor Tiberius publicly acknowledged the Cura Annonae as a personal and imperial duty, which if neglected would cause "the utter ruin of the state".

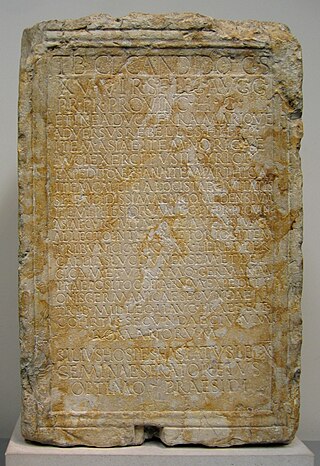

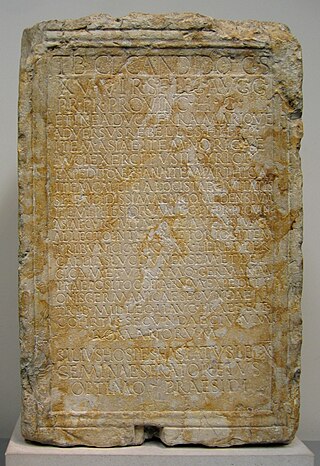

Tiberius Claudius Candidus was a Roman general and senator. He played an important role supporting Septimius Severus in the struggle for succession following the assassination of the emperor Pertinax in 193 CE.