A grimoire is a textbook of magic, typically including instructions on how to create magical objects like talismans and amulets, how to perform magical spells, charms, and divination, and how to summon or invoke supernatural entities such as angels, spirits, deities, and demons. In many cases, the books themselves are believed to be imbued with magical powers, although in many cultures, other sacred texts that are not grimoires have been believed to have supernatural properties intrinsically. The only contents found in a grimoire would be information on spells, rituals, the preparation of magical tools, and lists of ingredients and their magical correspondences. In this manner, while all books on magic could be thought of as grimoires, not all magical books should be thought of as grimoires.

Powwow, also called Brauche, Brauchau, or Braucherei in the Pennsylvania Dutch language, is a vernacular system of North American traditional medicine and folk magic originating in the culture of the Pennsylvania Dutch. Blending aspects of folk religion with healing charms, "powwowing" includes a wide range of healing rituals used primarily for treating ailments in humans and livestock, as well as securing physical and spiritual protection, and good luck in everyday affairs. Although the word "powwow" is Native American, these ritual traditions are of European origin and were brought to colonial Pennsylvania in the transatlantic migrations of German-speaking people from Central Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A practitioner is sometimes referred to as a "Powwower" or Braucher, but terminology varies by region. These folk traditions continue to the present day in both rural and urban settings, and have spread across North America.

Thaumaturgy is the purported capability of a magician to work magic or other paranormal events or a saint to perform miracles. It is sometimes translated into English as wonderworking.

Black magic has traditionally referred to the use of supernatural powers or magic for evil and selfish purposes.

A wand is a thin, light-weight rod that is held with one hand, and is traditionally made of wood, but may also be made of other materials, such as metal, plastic or stone. Long versions of wands are often styled in forms of staves or sceptres, which could have large ornamentation on the top.

The cunning folk were professional or semi-professional practitioners of magic in Europe from the medieval period through the early 20th century. In Britain they were known by a variety of names in different regions of the country, including wise men and wise women, pellars, wizards, dyn hysbys, and sometimes white witches.

An incantation, a spell, a charm, an enchantment, or a bewitchery, is a magical formula intended to trigger a magical effect on a person or objects. The formula can be spoken, sung, or chanted. An incantation can also be performed during ceremonial rituals or prayers. In the world of magic, wizards, witches, and fairies are common performers of incantations in culture and folklore.

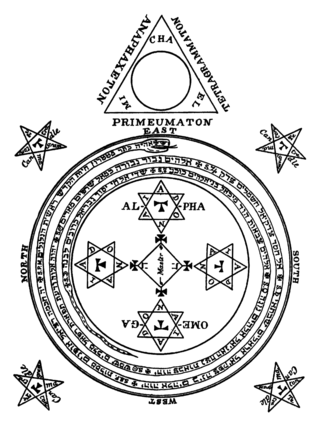

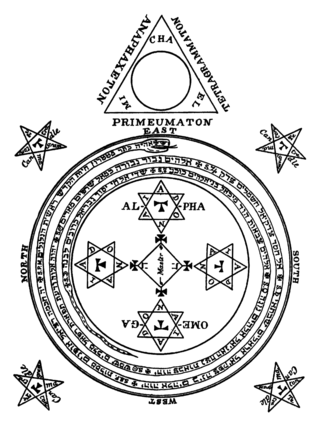

The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses is an 18th- or 19th-century magical text allegedly written by Moses, and passed down as hidden books of the Hebrew Bible. Self-described as "the wonderful arts of the old Hebrews, taken from the Mosaic books of the Kabbalah and the Talmud", it is actually a grimoire, or text of magical incantations and seals, that purports to instruct the reader in the spells used to create some of the miracles portrayed in the Bible as well as to grant other forms of good fortune and good health. The work contains reputed Talmudic magic names, words, and ideograms, some written in Hebrew and some with letters from the Latin alphabet. It contains "Seals" or magical drawings accompanied by instructions intended to help the user perform various tasks, from controlling weather or people to contacting the dead or Biblical religious figures.

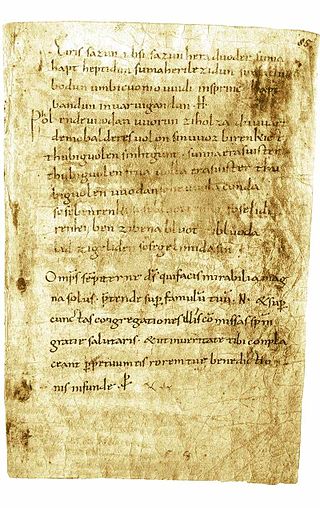

The Merseburg charms or Merseburg incantations are two medieval magic spells, charms or incantations, written in Old High German. They are the only known examples of Germanic pagan belief preserved in the language. They were discovered in 1841 by Georg Waitz, who found them in a theological manuscript from Fulda, written in the 9th century, although there remains some speculation about the date of the charms themselves. The manuscript is stored in the library of the cathedral chapter of Merseburg, hence the name.

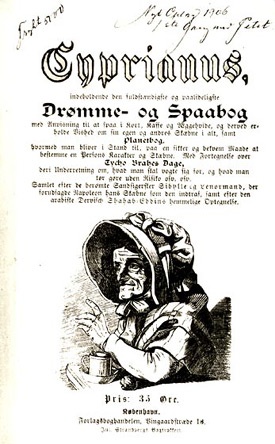

The Book of Saint Cyprian refers to different grimoires from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, all pseudepigraphically attributed to the 3rd century Saint Cyprian of Antioch. According to popular legend, Cyprian of Antioch was a pagan sorcerer who converted to Christianity.

Pow-Wows; or, Long Lost Friend is a book by John George Hohman published in 1820. Hohman was a Pennsylvania Dutch healer; the book is a collection of home- and folk-remedies, as well as spells and talismans.

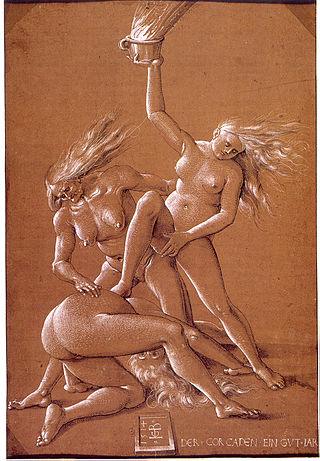

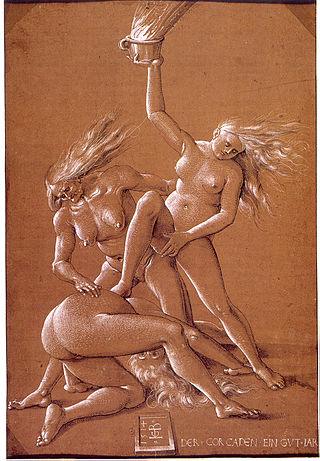

European witchcraft is a multifaceted historical and cultural phenomenon that unfolded over centuries, leaving a mark on the continent's social, religious, and legal landscapes. The roots of European witchcraft trace back to classical antiquity when concepts of magic and religion were closely related, and society closely integrated magic and supernatural beliefs. Ancient Rome, then a pagan society, had laws against harmful magic. In the Middle Ages, accusations of heresy and devil worship grew more prevalent. By the early modern period, major witch hunts began to take place, partly fueled by religious tensions, societal anxieties, and economic upheaval. Witches were often viewed as dangerous sorceresses or sorcerers in a pact with the Devil, capable of causing harm through black magic. A feminist interpretation of the witch trials is that misogynist views of women led to the association of women and malevolent witchcraft.

Saints Cyprian and Justina are honored in the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church and Oriental Orthodoxy as Christians of Antioch, who in 304, during the Diocletianic Persecution, suffered martyrdom at Nicomedia on September 26. According to Roman Catholic sources, no Bishop of Antioch bore the name of Cyprian.

Magic in the Greco-Roman world—that is, ancient Greece, ancient Rome, and the other cultures with which they interacted, especially ancient Egypt—comprises supernatural practices undertaken by individuals, often privately, that were not under the oversight of official priesthoods attached to the various state, community, and household cults and temples as a matter of public religion. Private magic was practiced throughout Greek and Roman cultures as well as among Jews and early Christians of the Roman Empire. Primary sources for the study of Greco-Roman magic include the Greek Magical Papyri, curse tablets, amulets, and literary texts such as Ovid's Fasti and Pliny the Elder's Natural History.

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's Natural History describes as "an object that protects a person from trouble". Anything can function as an amulet; items commonly so used include statues, coins, drawings, plant parts, animal parts, and written words.

The Secret Lore of Magic is a book by Idries Shah on the subject of magical texts. First published in 1957, it includes several major source-books of magical arts, translated from French, Latin, Hebrew and other tongues, annotated and fully illustrated with numerous diagrams, signs and characters. Together with Oriental Magic, which appeared in the preceding year, it provided an important literary-anthropological survey of magical literature and is a comprehensive reference for psychologists, ethnologists and others interested in the rise and development of human beliefs.

Cunning folk, also known as folk healers or wise folk, were practitioners of folk medicine, helpful folk magic and divination in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 20th century. Their practices were known as the cunning craft. Their services also included thwarting witchcraft. Although some cunning folk were denounced as witches themselves, they made up a minority of those accused, and the common people generally made a distinction between the two. The name 'cunning folk' originally referred to folk-healers and magic-workers in Britain, but the name is now applied as an umbrella term for similar people in other parts of Europe.

In the folklore of Scandinavia, Tycho Brahe days are days judged to be especially unlucky, especially for magical work, and important business transactions. Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) was a Danish astronomer, astrologer, and alchemist and as such achieved some acclaim in popular folklore as a sage and magician.

The Grand Albert is a grimoire that has often been attributed to Albertus Magnus. Begun perhaps around 1245, it received its definitive form in Latin around 1493, a French translation in 1500, and its most expansive and well-known French edition in 1703. Its original Latin title, Liber secretorum Alberti Magni de virtutibus herbarum, lapidum et animalium quorumdam, translates to English as "the book of secrets of Albert the Great on the virtues of herbs, stones and certain animals". It is also known under the names of The Secrets of Albert, Secreta Alberti, and Experimenta Alberti.

Goetia is a type of European sorcery, often referred to as witchcraft, that has been transmitted through grimoires—books containing instructions for performing magical practices. The term "goetia" finds its origins in the Greek word "goes", which originally denoted diviners, magicians, healers, and seers. Initially, it held a connotation of low magic, implying fraudulent or deceptive mageia as opposed to theurgy, which was regarded as divine magic. Grimoires, also known as "books of spells" or "spellbooks," serve as instructional manuals for various magical endeavors. They cover crafting magical objects, casting spells, performing divination, and summoning supernatural entities like angels, spirits, deities, and demons. Although the term "grimoire" originates from Europe, similar magical texts have been found in diverse cultures across the world.