This article covers the history and bibliography of Romania and links to specialized articles.

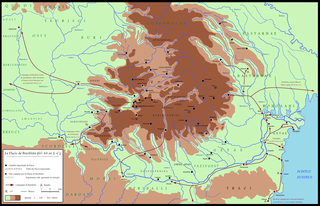

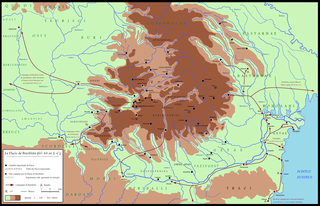

Dacia was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It thus roughly corresponds to the present-day countries of Romania, as well as parts of Moldova, Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Ukraine.

Moesia was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans south of the Danube River, which included most of the territory of modern eastern Serbia, Kosovo, north-eastern Albania, northern parts of North Macedonia, Northern Bulgaria, Romanian Dobruja and small parts of Southern Ukraine.

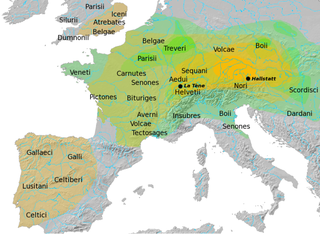

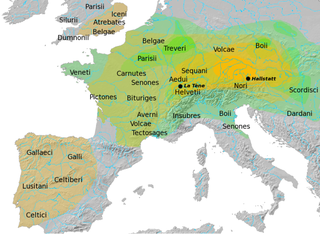

The Dacians were the ancient Indo-European inhabitants of the cultural region of Dacia, located in the area near the Carpathian Mountains and west of the Black Sea. They are often considered a subgroup of the Thracians. This area includes mainly the present-day countries of Romania and Moldova, as well as parts of Ukraine, Eastern Serbia, Northern Bulgaria, Slovakia, Hungary and Southern Poland. The Dacians and the related Getae spoke the Dacian language, which has a debated relationship with the neighbouring Thracian language and may be a subgroup of it. Dacians were somewhat culturally influenced by the neighbouring Scythians and by the Celtic invaders of the 4th century BC.

Decebalus, sometimes referred to as Diurpaneus, was the last Dacian king. He is famous for fighting three wars, with varying success, against the Roman Empire under two emperors. After raiding south across the Danube, he defeated a Roman invasion in the reign of Domitian, securing a period of independence during which Decebalus consolidated his rule.

Burebista was the king of the Getae and Dacian tribes from 82/61 BC to 45/44 BC. He was the first king who successfully unified the tribes of the Dacian kingdom, which comprised the area located between the Danube, Tisza, and Dniester rivers, and modern day Romania and Moldova. In the 7th and 6th centuries BC it became home to the Thracian peoples, including the Getae and the Dacians. From the 4th century to the middle of the 2nd century BC the Dacian peoples were influenced by La Tène Celts who brought new technologies with them into Dacia. Sometime in the 2nd century BC the Dacians expelled the Celts from their lands. Dacians often warred with neighbouring tribes, but the relative isolation of the Dacian peoples in the Carpathian Mountains allowed them to survive and even to thrive. By the 1st century BC the Dacians had become the dominant power.

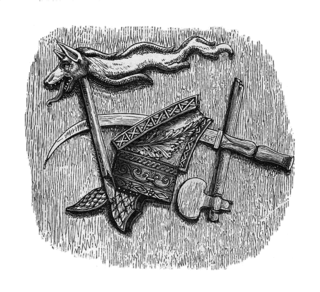

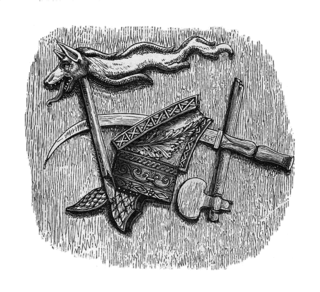

The falx was a weapon with a curved blade that was sharp on the inside edge used by the Thracians and Dacians. The name was later applied to a siege hook used by the Romans.

The Dacian Wars were two military campaigns fought between the Roman Empire and Dacia during Emperor Trajan's rule. The conflicts were triggered by the constant Dacian threat on the Danubian province of Moesia and also by the increasing need for resources of the economy of the Empire.

Domitian's Dacian War was a conflict between the Roman Empire and the Dacian Kingdom, which had invaded the province of Moesia. The war occurred during the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian, in the years 86–88 AD.

The military history of Romania deals with conflicts spreading over a period of about 2500 years across the territory of modern Romania, the Balkan Peninsula and Eastern Europe and the role of the Romanian military in conflicts and peacekeeping worldwide.

Duras, also known as Duras-Diurpaneus, was king of the Dacians between the years AD 69 and 87, during the time that Domitian ruled the Roman Empire. He was one of a series of rulers following the Great King Burebista. Duras' immediate successor was Decebalus.

Dava was a Geto-Dacian name for a city, town or fortress. Generally, the name indicated a tribal center or an important settlement, usually fortified. Some of the Dacian settlements and the fortresses employed the Murus Dacicus traditional construction technique.

The appearance of Celts in Transylvania can be traced to the later La Tène period . Excavation of the great La Tène necropolis at Apahida, Cluj County, by S. Kovacs at the turn of the 20th century revealed the first evidence of Celtic culture in Romania. The 3rd–2nd century BC site is remarkable for its cremation burials and chiefly wheel-made funeral vessels.

Roman Dacia was a province of the Roman Empire from 106 to 271–275 AD. Its territory consisted of what are now the regions of Oltenia, Transylvania and Banat. During Roman rule, it was organized as an imperial province on the borders of the empire. It is estimated that the population of Roman Dacia ranged from 650,000 to 1,200,000. It was conquered by Trajan (98–117) after two campaigns that devastated the Dacian Kingdom of Decebalus. However, the Romans did not occupy its entirety; Crișana, Maramureș, and most of Moldavia remained under the Free Dacians.

This section of the timeline of Romanian history concerns events from Late Neolithic until Late Antiquity, which took place in or are directly related with the territory of modern Romania.

The Antiquity in Romania spans the period between the foundation of Greek colonies in present-day Dobruja and the withdrawal of the Romans from "Dacia Trajana" province. The earliest records of the history of the regions which now form Romania were made after the establishment of three Greek towns—Histria, Tomis, and Callatis—on the Black Sea coast in the 7th and 6th centuries BC. They developed into important centers of commerce and had a close relationship with the natives. The latter were first described by Herodotus, who made mention of the Getae of the Lower Danube region, the Agathyrsi of Transylvania and the Sygannae of Crişana.

The Battle of Histria, c. 62–61 B.C., was fought between the Bastarnae peoples of Scythia Minor and the Roman Consul Gaius Antonius Hybrida. The Bastarnae emerged victorious from the battle after successfully launching a surprise attack on the Roman troops; Hybrida escaped alongside his cavalry forces leaving behind the infantry to be massacred by the Bastarnian-Scythian attackers.