In Greek mythology, Agamemnon was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Greeks during the Trojan War. He was the son of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the husband of Clytemnestra, and the father of Iphigenia, Iphianassa, Electra, Laodike, Orestes and Chrysothemis. Legends make him the king of Mycenae or Argos, thought to be different names for the same area. Agamemnon was killed upon his return from Troy by Clytemnestra, or in an older version of the story, by Clytemnestra's lover Aegisthus.

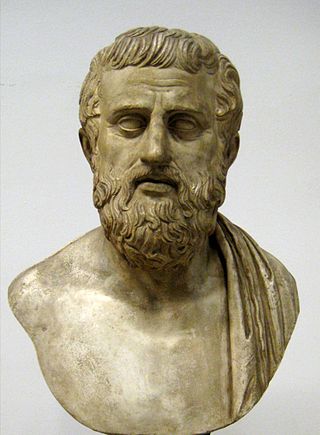

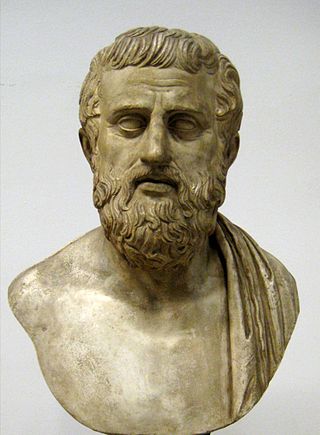

Aeschylus was an ancient Greek tragedian often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is largely based on inferences made from reading his surviving plays. According to Aristotle, he expanded the number of characters in the theatre and allowed conflict among them. Formerly, characters interacted only with the chorus.

A demon is a malevolent supernatural entity. Historically, belief in demons, or stories about demons, occurs in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology, and folklore; as well as in media such as comics, video games, movies, and television series.

Sophocles was an ancient Greek tragedian, known as one of three from whom at least one play has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or contemporary with, those of Aeschylus; and earlier than, or contemporary with, those of Euripides. Sophocles wrote over 120 plays, but only seven have survived in a complete form: Ajax, Antigone, Women of Trachis, Oedipus Rex, Electra, Philoctetes and Oedipus at Colonus. For almost fifty years, Sophocles was the most celebrated playwright in the dramatic competitions of the city-state of Athens which took place during the religious festivals of the Lenaea and the Dionysia. He competed in thirty competitions, won twenty-four, and was never judged lower than second place. Aeschylus won thirteen competitions, and was sometimes defeated by Sophocles; Euripides won four.

In Greek mythology, Kratos, also known as Cratus or Cratos, is the divine personification of strength. He is the son of Pallas and Styx. Kratos and his siblings Nike ('Victory'), Bia ('Force'), and Zelus ('Glory') are all the personification of a specific trait. Kratos is first mentioned alongside his siblings in Hesiod's Theogony. According to Hesiod, Kratos and his siblings dwell with Zeus because their mother Styx came to him first to request a position in his regime, so he honored her and her children with exalted positions. Kratos and his sister Bia are best known for their appearance in the opening scene of Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound. Acting as agents of Zeus, they lead the captive Titan Prometheus on stage. Kratos compels the mild-mannered blacksmith god Hephaestus to chain Prometheus to a rock as punishment for his theft of fire.

Phobos is the god and personification of fear and panic in Greek mythology. Phobos was the son of Ares and Aphrodite, and the brother of Deimos. He does not have a major role in mythology outside of being his father's attendant.

Electra, also spelt Elektra, is one of the most popular mythological characters in tragedies. She is the main character in two Greek tragedies, Electra by Sophocles and Electra by Euripides. She is also the central figure in plays by Aeschylus, Alfieri, Voltaire, Hofmannsthal, and Eugene O'Neill. She is a vengeful soul in The Libation Bearers, the second play of Aeschylus' Oresteia trilogy. She plans out an attack with her brother to kill their mother, Clytemnestra.

In Greek mythology, Geryon, son of Chrysaor and Callirrhoe, the grandson of Medusa and the nephew of Pegasus, was a fearsome giant who dwelt on the island Erytheia of the mythic Hesperides in the far west of the Mediterranean. A more literal-minded later generation of Greeks associated the region with Tartessos in southern Iberia. Geryon was often described as a monster with either three bodies and three heads, or three heads and one body, or three bodies and one head. He is commonly accepted as being mostly humanoid, with some distinguishing features and in mythology, famed for his cattle.

The Oresteia is a trilogy of Greek tragedies written by Aeschylus in the 5th century BCE, concerning the murder of Agamemnon by Clytemnestra, the murder of Clytemnestra by Orestes, the trial of Orestes, the end of the curse on the House of Atreus and the pacification of the Furies.

The udug, later known in Akkadian as the utukku, were an ambiguous class of demons from ancient Mesopotamian mythology. They were different from the dingir and they were generally malicious, even if a member of demons (Pazuzu) was willing to clash both with other demons and with the gods, even if he is described as a hostile presence to man. The word is generally ambiguous and is sometimes used to refer to demons as a whole rather than a specific kind of demon. No visual representations of the udug have yet been identified, but descriptions of it ascribe to it features often given to other ancient Mesopotamian demons: a dark shadow, absence of light surrounding it, poison, and a deafening voice. The surviving ancient Mesopotamian texts giving instructions for exorcizing the evil udug are known as the Udug Hul texts. These texts emphasize the evil udug's role in causing disease and the exorcist's role in curing the disease.

Psychological horror is a subgenre of horror and psychological fiction with a particular focus on mental, emotional, and psychological states to frighten, disturb, or unsettle its audience. The subgenre frequently overlaps with the related subgenre of psychological thriller, and often uses mystery elements and characters with unstable, unreliable, or disturbed psychological states to enhance the suspense, horror, drama, tension, and paranoia of the setting and plot and to provide an overall creepy, unpleasant, unsettling, or distressing atmosphere.

Daimon or daemon originally referred to a lesser deity or guiding spirit such as the daimons of ancient Greek religion and mythology and of later Hellenistic religion and philosophy. The word is derived from Proto-Indo-European daimon "provider, divider ," from the root *da- "to divide". Daimons were possibly seen as the souls of men of the golden age acting as tutelary deities, according to entry δαίμων at Liddell & Scott. See also daimonic: a religious, philosophical, literary and psychological concept.

Greek tragedy is one of the three principal theatrical genres from Ancient Greece and Greek inhabited Anatolia, along with comedy and the satyr play. It reached its most significant form in Athens in the 5th century BC, the works of which are sometimes called Attic tragedy.

Daimon Hellstrom, also known as the Son of Satan and Hellstorm, is a fictional character appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics.

A cacodemon is an evil spirit or a demon. The opposite of a cacodemon is an agathodaemon or eudaemon, a good spirit or angel. The word cacodemon comes through Latin from the Ancient Greek κακοδαίμων kakodaimōn, meaning an "evil spirit", whereas daimon would be a neutral spirit in Greek. It is believed to be capable of shapeshifting. A cacodemon is also said to be a malevolent person.

A demon is a malevolent supernatural being in religion, occultism, mythology, folklore, and fiction.

Jungian archetypes are a concept from psychology that refers to a universal, inherited idea, pattern of thought, or image that is present in the collective unconscious of all human beings. The psychic counterpart of instinct, archetypes are thought to be the basis of many of the common themes and symbols that appear in stories, myths, and dreams across different cultures and societies. Some examples of archetypes include those of the mother, the child, the trickster, and the flood, among others. The concept of the collective unconscious was first proposed by Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst.

Stephen A. Diamond is an American clinical and forensic psychologist, a former pupil and protégé of Dr. Rollo May, and notable author of Anger, Madness, and the Daimonic: The Psychological Genesis of Violence, Evil, and Creativity. His work focuses on the psychological topics of anger, violence, evil, mental illness, and the daimonic.

The eudaemon, eudaimon, or eudemon in Greek mythology was a type of daemon or genius (deity), which in turn was a kind of spirit. A eudaemon was regarded as a good spirit or angel, and the evil cacodaemon was its opposing spirit.

De genio Socratis is a work by Plutarch, part of his collection of works entitled Moralia.