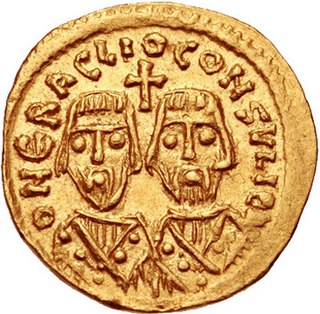

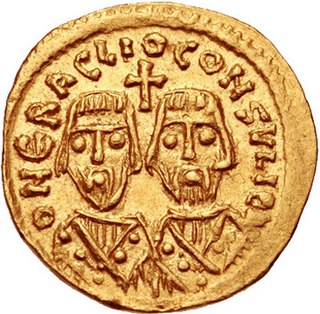

Heraclius was Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revolt against the unpopular usurper Phocas.

The 610s decade ran from January 1, 610, to December 31, 619.

Year 628 (DCXXVIII) was a leap year starting on Friday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 628 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Year 619 (DCXIX) was a common year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 619 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Shahrbaraz, was shah (king) of the Sasanian Empire from 27 April 630 to 9 June 630. He usurped the throne from Ardashir III, and was killed by Iranian nobles after forty days. Before usurping the Sasanian throne he was a spahbed (general) under Khosrow II (590–628). He is furthermore noted for his important role during the climactic Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, and the events that followed afterwards.

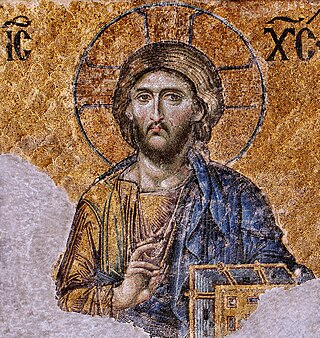

Byzantine art comprises the body of artistic products of the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire. Though the empire itself emerged from the decline of Rome and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the start date of the Byzantine period is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if still imprecise. Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Islamic states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries afterward.

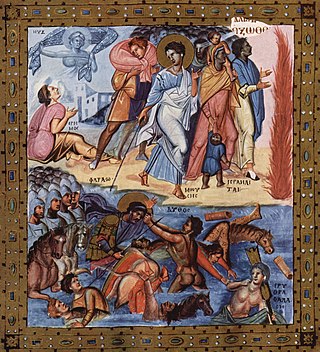

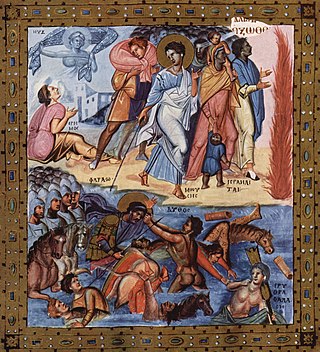

The Paris Psalter is a Byzantine illuminated manuscript, 38 x 26.5 cm in size, containing 449 folios and 14 full-page miniatures. The Paris Psalter is considered a key monument of the so-called Macedonian Renaissance, a 10th-century renewal of interest in classical art closely identified with the emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (909-959) and his immediate successors.

Heraclius' campaign of 622, erroneously also known as the Battle of Issus, was a major campaign in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 by emperor Heraclius that culminated in a crushing Byzantine victory in Anatolia.

Macedonian art is the art of the Macedonian Renaissance in Byzantine art. The period followed the end of the Byzantine iconoclasm and lasted until the fall of the Macedonian dynasty, which ruled the Byzantine Empire from 867 to 1056, having originated in the theme of Macedonia. It coincided with the Ottonian Renaissance in Western Europe. In the 9th and 10th centuries, the Byzantine Empire's military situation improved, and art and architecture revived.

The Jewish revolt against Heraclius was part of the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 and is considered the last serious Jewish attempt to gain autonomy in Palaestina Prima prior to modern times.

Heraclius the Elder was a Byzantine general and the father of Byzantine emperor Heraclius. Generally considered to be of Armenian origin Heraclius the Elder distinguished himself in the war against the Sassanid Persians in the 580s. As a subordinate general, Heraclius served under the command of Philippicus during the Battle of Solachon and possibly served under Comentiolus during the Battle of Sisarbanon. In circa 595, Heraclius the Elder is mentioned as a magister militum per Armeniam sent by Emperor Maurice to quell an Armenian rebellion led by Samuel Vahewuni and Atat Khorkhoruni. In circa 600, he was appointed as the Exarch of Africa and in 608, Heraclius the Elder rebelled with his son against the usurper Phocas. Using North Africa as a base, the younger Heraclius managed to overthrow Phocas, beginning the Heraclian dynasty, which would rule Byzantium for a century. Heraclius the Elder died soon after receiving news of his son's accession to the Byzantine throne.

The Perso-Turkic war of 627–629 was the third and final conflict between the Sasanian Empire and the Western Turkic Khaganate. Unlike the previous two wars, it was not fought in Central Asia, but in Transcaucasia. Hostilities were initiated in 627 AD by Tong Yabghu Qaghan of the Western Göktürks and Emperor Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire. Opposing them were the Sassanid Persians, allied with the Avars. The war was fought against the background of the last Byzantine-Sassanid War and served as a prelude to the dramatic events that changed the balance of powers in the Middle East for centuries to come.

The Sasanian conquest of Jerusalem was a significant event in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, having taken place in early 614. Amidst the conflict, Sasanian king Khosrow II had appointed Shahrbaraz, his spahbod, to lead an offensive into the Diocese of the East of the Byzantine Empire. Under Shahrbaraz, the Sasanian army had secured victories at Antioch as well as at Caesarea Maritima, the administrative capital of Palaestina Prima. By this time, the grand inner harbour had silted up and was useless, but the city continued to be an important maritime hub after Byzantine emperor Anastasius I Dicorus ordered the reconstruction of the outer harbour. Successfully capturing the city and the harbour had given the Sasanian Empire strategic access to the Mediterranean Sea. The Sasanians' advance was accompanied by the outbreak of a Jewish revolt against Heraclius; the Sasanian army was joined by Nehemiah ben Hushiel and Benjamin of Tiberias, who enlisted and armed Jews from across Galilee, including the cities of Tiberias and Nazareth. In total, between 20,000 and 26,000 Jewish rebels took part in the Sasanian assault on Jerusalem. By mid-614, the Jews and the Sasanians had captured the city, but sources vary on whether this occurred without resistance or after a siege and breaching of the wall with artillery.

The Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 was the final and most devastating of the series of wars fought between the Byzantine / Roman Empire and the Sasanian Empire of Iran. The previous war between the two powers had ended in 591 after Emperor Maurice helped the Sasanian king Khosrow II regain his throne. In 602 Maurice was murdered by his political rival Phocas. Khosrow declared war, ostensibly to avenge the death of the deposed emperor Maurice. This became a decades-long conflict, the longest war in the series, and was fought throughout the Middle East: in Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Caucasus, Anatolia, Armenia, the Aegean Sea and before the walls of Constantinople itself.

The First Cyprus Treasure or Lamboussa Treasure is the name of a major early Byzantine silver hoard found near Kyrenia, Cyprus. Currently in the British Museum's collection, the treasure is largely composed of liturgical objects that may have belonged to an ancient church or monastery. It is called the First Cyprus Treasure to distinguish it from the so-called Second Cyprus Treasure, which is now split between the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Cyprus Museum.

The Lampsacus Treasure or Lapseki Treasure is the name of an important early Byzantine silver hoard found near the town of Lapseki in modern-day Turkey. Most of the hoard is now in the British Museum's collection, although a few items can be found in museums in Paris and Istanbul too.

Sasanian Egypt refers to the brief rule of Egypt and parts of Libya by the Sasanian Empire, following the Sasanian conquest of Egypt. It lasted from 618 to 628, until the Sasanian general Shahrbaraz made an alliance with the Roman Byzantine emperor Heraclius to have control over Egypt returned to him.

Silver was important in Byzantine art and society more broadly as it was the most precious metal right after gold. Byzantine silver was prized in official, religious, and domestic realms. Aristocratic homes had silver dining ware, and in churches silver was used for crosses, liturgical vessels such as the patens and chalices required for every Eucharist. The imperial offices periodically issued silver coinage and regulated the use of silver through control stamps. About 1,500 silver plates and crosses survive from the Byzantine era.

David was one of three co-emperors of Byzantium for a few months in late 641, and had the regnal name Tiberius. David was the son of Emperor Heraclius and his wife and niece Empress Martina. He was born after the emperor and empress had visited Jerusalem and his given name reflects a deliberate attempt to link the imperial family with the Biblical David. The David Plates, which depict the life of King David, may likewise have been created for the young prince or to commemorate his birth. David was given the senior court title caesar in 638, in a ceremony during which he received the kamelaukion cap previously worn by his older brother Heraclonas.