Related Research Articles

In Māori mythology, Tāwhaki is a semi-supernatural being associated with lightning and thunder.

Whaitiri is a female atua and personification of thunder in Māori mythology. She is the grandmother of Tāwhaki and Karihi. Whaitiri is the granddaughter of Te Kanapu, son of Te Uira, both of whom are personified forms of lightning. Another more primary atua of thunder, a male, is Tāwhirimātea.

In Māori mythology, Wahieroa is a son of Tāwhaki, and father of Rātā.

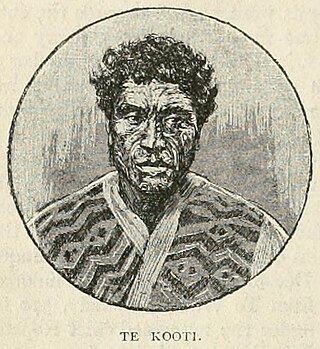

Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki was a Māori leader, the founder of the Ringatū religion and guerrilla fighter.

The Invasion of the Waikato became the largest and most important campaign of the 19th-century New Zealand Wars. Hostilities took place in the North Island of New Zealand between the military forces of the colonial government and a federation of Māori tribes known as the Kingitanga Movement. The Waikato is a territorial region with a northern boundary somewhat south of the present-day city of Auckland. The campaign lasted for nine months, from July 1863 to April 1864. The invasion was aimed at crushing Kingite power and also at driving Waikato Māori from their territory in readiness for occupation and settlement by European colonists. The campaign was fought by a peak of about 14,000 Imperial and colonial troops and about 4,000 Māori warriors drawn from more than half the major North Island tribal groups.

The Tauranga campaign was a six-month-long armed conflict in New Zealand's Bay of Plenty in early 1864, and part of the New Zealand Wars that were fought over issues of land ownership and sovereignty. The campaign was a sequel to the invasion of Waikato, which aimed to crush the Māori King (Kingitanga) Movement that was viewed by the colonial government as a challenge to the supremacy of the British monarchy.

Haka are a variety of ceremonial dances in Māori culture. A performance art, haka are often performed by a group, with vigorous movements and stamping of the feet with rhythmically shouted accompaniment. Haka have been traditionally performed by both men and women for a variety of social functions within Māori culture. They are performed to welcome distinguished guests, or to acknowledge great achievements, occasions, or funerals.

A lament or lamentation is a passionate expression of grief, often in music, poetry, or song form. The grief is most often born of regret, or mourning. Laments can also be expressed in a verbal manner in which participants lament about something that they regret or someone that they have lost, and they are usually accompanied by wailing, moaning and/or crying. Laments constitute some of the oldest forms of writing, and examples exist across human cultures.

Kawhia Harbour is one of three large natural inlets in the Tasman Sea coast of the Waikato region of New Zealand's North Island. It is located to the south of Raglan Harbour, Ruapuke and Aotea Harbour, 40 kilometres southwest of Hamilton. Kawhia is part of the Ōtorohanga District and is in the King Country. It has a high-tide area of 68 km2 (26 sq mi) and a low-tide area of 18 km2 (6.9 sq mi). Te Motu Island is located in the harbour.

Waka are Māori watercraft, usually canoes ranging in size from small, unornamented canoes used for fishing and river travel to large, decorated war canoes up to 40 metres (130 ft) long.

The Pai Mārire movement was a syncretic Māori religion founded in Taranaki by the prophet Te Ua Haumēne. It flourished in the North Island from about 1863 to 1874. Pai Mārire incorporated biblical and Māori spiritual elements and promised its followers deliverance from 'pākehā' (British) domination. Although founded with peaceful motives—its name means "Good and Peaceful"—Pai Mārire became known for an extremist form of the religion known to the Europeans as "Hauhau". The rise and spread of the violent expression of Pai Mārire was largely a response to the New Zealand Government's military operations against North Island Māori, which were aimed at exerting European sovereignty and gaining more land for white settlement; historian B.J. Dalton claims that after 1865 Māori in arms were almost invariably termed Hauhau.

Whakatau was a supernatural person in Māori mythology.

Māori mythology and Māori traditions are two major categories into which the remote oral history of New Zealand's Māori may be divided. Māori myths concern tales of supernatural events relating to the origins of what was the observable world for the pre-European Māori, often involving gods and demigods. Māori tradition concerns more folkloric legends often involving historical or semi-historical forebears. Both categories merge in whakapapa to explain the overall origin of the Māori and their connections to the world which they lived in.

Professional mourning or paid mourning is an occupation that originates from Egyptian, Chinese, Mediterranean and Near Eastern cultures. Professional mourners, also called moirologists and mutes, are compensated to lament or deliver a eulogy and help comfort and entertain the grieving family. Mentioned in the Bible and other religious texts, the occupation is widely invoked and explored in literature, from the Ugaritic epics of early centuries BC to modern poetry.

Vajtim or Gjëmë is the dirge or lamentation of the dead in the Albanian custom by a group of men or a woman or a group of women. Cries have now become extinct both in the Islamic and Christian Albanian Population, except in some parts Northern Albania and Kosovo as well as in parts of North Macedonia such as Zajas and Upper Reka, where they exist in a very diminished form. The earliest figurative representations of this practice in traditional Albanian-inhabited regions appear on Dardanian funerary stelae of classical antiquity.

Feminism in New Zealand is a series of actions and a philosophy to advance rights for women in New Zealand. This can be seen to have taken place through parliament and legislation, and also by actions and role modelling by significant women and groups of people throughout New Zealand's history. The women's suffrage movement in New Zealand succeeded in 1893 when New Zealand became the first nation where all women were awarded the right to vote. New Zealand was also the first country in the world in which the five highest offices of power were held by women, which occurred between March 2005 and August 2006, with Queen Elizabeth II, Governor-General Silvia Cartwright, Prime Minister Helen Clark, Speaker of the New Zealand House of Representatives Margaret Wilson and Chief Justice Sian Elias.

Rangiaowhia was, for over 20 years, a thriving village on a ridge between two streams in the Waikato region, about 4 km (2.5 mi) east of Te Awamutu. From 1841 it was the site of a very productive Māori mission station until the Invasion of the Waikato in 1864. The station served Ngāti Hinetu and Ngāti Apakura. Only a church remains from those days, the second oldest Waikato building.

The Ngawait, also spelt Ngawadj and other variations, and also known as Eritark and other names, were an Aboriginal Australian people of the mid-Riverland region, spanning the Murray River in South Australia. They have sometimes been referred to as part of the Meru people, a larger grouping which could also include the Ngaiawang and Erawirung peoples. There were at least two clans or sub-groups of the Ngawait people, the Barmerara Meru and Muljulpero maru.

Whatihua was a Māori rangatira (chief) in the Tainui confederation of tribes, based at Kāwhia, New Zealand. He quarrelled with his brother, Tūrongo, and as a result Tainui was split between them, with Whatihua receiving the northern Waikato region, including Kāwhia. He probably lived in the early sixteenth century.

Rua-pū-tahanga was a Māori puhi ariki (chieftainess) from Ngāti Ruanui, who married Whatihua and thus became the ancestor of many tribes of Tainui. She probably lived in the sixteenth century.

References

- ↑ Journal of Expeditions of Discovery into Central Australia And Overland From Adelaide To King George's Sound in the Years 1840-1, Edward Eyre

- ↑ Morowari (Murawari) Riverina, New South Wales

- 1 2 Galvany, Albert (2012). "Death and Ritual Wailing in Early China: Around the Funeral of Lao Dan". Asia Major. 25 (2): 15–42. JSTOR 43486144.

- ↑ Green, Laura C.; Beckwith, Martha Warren (1926). "Hawaiian Customs and Beliefs Relating to Sickness and Death". American Anthropologist. 28 (1): 176–208 (177–8). doi:10.1525/aa.1926.28.1.02a00030. ISSN 0002-7294.