The Delian League, founded in 478 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Plataea at the end of the Second Persian invasion of Greece.

The Peloponnesian War was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time, until the decisive intervention of the Persian Empire in support of Sparta. Led by Lysander, the Spartan fleet, built with Persian subsidies, finally defeated Athens and started a period of Spartan hegemony over Greece.

The Peloponnesian League was an alliance of ancient Greek city-states, dominated by Sparta and centred on the Peloponnese, which lasted from c.550 to 366 BC. It is known mainly for being one of the two rivals in the Peloponnesian War, against the Delian League, which was dominated by Athens.

This article concerns the period 439 BC – 430 BC.

This decade witnessed the continuing decline of the Achaemenid Empire, fierce warfare amongst the Greek city-states during the Peloponnesian War, the ongoing Warring States period in Zhou dynasty China, and the closing years of the Olmec civilization in modern-day Mexico.

Lysander was a Spartan military and political leader. He destroyed the Athenian fleet at the Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC, forcing Athens to capitulate and bringing the Peloponnesian War to an end. He then played a key role in Sparta's domination of Greece for the next decade until his death at the Battle of Haliartus.

Epaminondas was a Greek general and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greek city-state of Thebes, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a pre-eminent position in Greek politics called the Theban Hegemony. In the process, he broke Spartan military power with his victory at Leuctra and liberated the Messenian helots, a group of Peloponnesian Greeks who had been enslaved under Spartan rule for some 230 years following their defeat in the Third Messenian War ending in 600 BC. Epaminondas reshaped the political map of Greece, fragmented old alliances, created new ones, and supervised the construction of entire cities. He was also militarily influential and invented and implemented several important battlefield tactics.

The Greco-Persian Wars were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the Greeks and the enormous empire of the Persians began when Cyrus the Great conquered the Greek-inhabited region of Ionia in 547 BC. Struggling to control the independent-minded cities of Ionia, the Persians appointed tyrants to rule each of them. This would prove to be the source of much trouble for the Greeks and Persians alike.

The Corinthian War was a conflict in ancient Greece which pitted Sparta against a coalition of city-states comprising Thebes, Athens, Corinth and Argos, backed by the Achaemenid Empire. The war was caused by dissatisfaction with Spartan imperialism in the aftermath of the Peloponnesian War, both from Athens, the defeated side in that conflict, and from Sparta's former allies, Corinth and Thebes, who had not been properly rewarded. Taking advantage of the fact that the Spartan king Agesilaus II was away campaigning in Asia against the Achaemenid Empire, Thebes, Athens, Corinth and Argos forged an alliance in 395 BC with the goal of ending Spartan hegemony over Greece; the allies' war council was located in Corinth, which gave its name to the war. By the end of the conflict, the allies had failed to end Spartan hegemony over Greece, although Sparta was durably weakened by the war.

The Battle of Chaeronea was fought in 338 BC, near the city of Chaeronea in Boeotia, between Macedonia under Philip II and an alliance of city-states led by Athens and Thebes. The battle was the culmination of Philip's final campaigns in 339–338 BC and resulted in a decisive victory for the Macedonians and their allies.

The Battle of Nemea, also known in ancient Athens as the Battle of Corinth, was a battle in the Corinthian War, between Sparta and the coalition of Argos, Athens, Corinth, and Thebes. The battle was fought in Corinthian territory, at the dry bed of the Nemea River. The battle was a decisive Spartan victory, which, coupled with the Battle of Coronea later in the same year, gave Sparta the advantage in the early fighting on the Greek mainland.

The idea of the Common Peace was one of the most influential concepts of 4th century BC Greek political thought, along with the idea of Panhellenism. The term described both the concept of a desirable, permanent peace between the Greek city-states (poleis) and a sort of peace treaty which fulfilled the three fundamental criteria of this concept: it had to include all the Greek city-states, it had to recognise the autonomy and equality of all city states without regard for their military power, and it had to be intended to remain in force permanently.

Pentecontaetia is the term used to refer to the period in Ancient Greek history between the defeat of the second Persian invasion of Greece at Plataea in 479 BC and the beginning of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC. The term originated with a scholiast commenting on Thucydides, who used it in their description of the period. The Pentecontaetia was marked by the rise of Athens as the dominant state in the Greek world and by the rise of Athenian democracy, a period also known as Golden Age of Athens. Since Thucydides focused his account on these developments, the term is generally used when discussing developments in and involving Athens.

The First Peloponnesian War was fought between Sparta as the leaders of the Peloponnesian League and Sparta's other allies, most notably Thebes, and the Delian League led by Athens with support from Argos. This war consisted of a series of conflicts and minor wars, such as the Second Sacred War. There were several causes for the war including the building of the Athenian long walls, Megara's defection and the envy and concern felt by Sparta at the growth of the Athenian Empire.

The Second Athenian League was a maritime confederation of Aegean city-states from 378 to 355 BC and headed by Athens, primarily for self-defense against the growth of Sparta and secondly, the Persian Empire.

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years in Ancient Greece, marked by much of the eastern Aegean and northern regions of Greek culture gaining increased autonomy from the Persian Empire; the peak flourishing of democratic Athens; the First and Second Peloponnesian Wars; the Spartan and then Theban hegemonies; and the expansion of Macedonia under Philip II. Much of the early defining politics, artistic thought, scientific thought, theatre, literature and philosophy of Western civilization derives from this period of Greek history, which had a powerful influence on the later Roman Empire. Part of the broader era of classical antiquity, the classical Greek era ended after Philip II's unification of most of the Greek world against the common enemy of the Persian Empire, which was conquered within 13 years during the wars of Alexander the Great, Philip's son.

The history of Sparta describes the history of the ancient Doric Greek city-state known as Sparta from its beginning in the legendary period to its incorporation into the Achaean League under the late Roman Republic, as Allied State, in 146 BC, a period of roughly 1000 years. Since the Dorians were not the first to settle the valley of the Eurotas River in the Peloponnesus of Greece, the preceding Mycenaean and Stone Age periods are described as well. Sparta went on to become a district of modern Greece. Brief mention is made of events in the post-classical periods.

The Wars of the Delian League were a series of campaigns fought between the Delian League of Athens and her allies, and the Achaemenid Empire of Persia. These conflicts represent a continuation of the Greco-Persian Wars, after the Ionian Revolt and the first and second Persian invasions of Greece.

The Theban–Spartan War of 378–362 BC was a series of military conflicts fought between Sparta and Thebes for hegemony over Greece. Sparta had emerged victorious from the Peloponnesian War against Athens, and occupied an hegemonic position over Greece. However, the Spartans' violent interventionism upset their former allies, especially Thebes and Corinth. The resulting Corinthian War ended with a difficult Spartan victory, but the Boeotian League headed by Thebes was also disbanded.

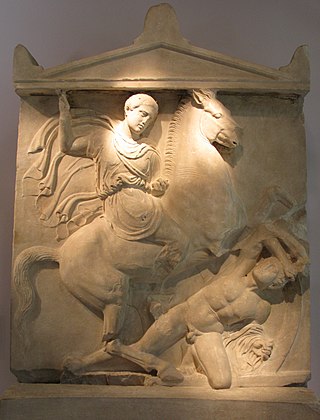

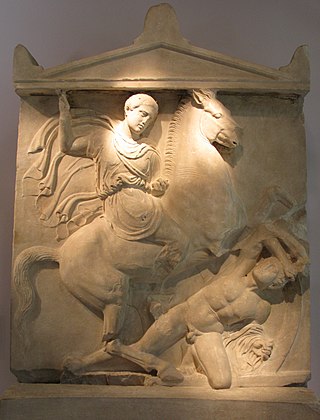

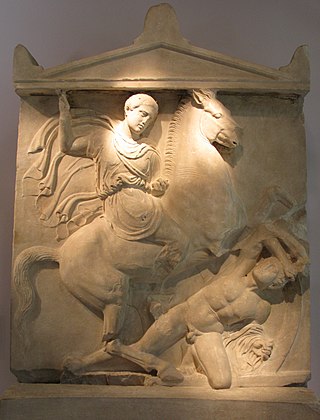

Pythion of Megara was a citizen of Megara who was commemorated for his courage in battle and for saving three Athenian tribes from death. His existence is known from an inscription on a commemorative stele found in the grave area outside the Acharnian Gate in Classical Athens. Pythion's actions are significant within the context of the campaigns in 446 BC that marked the closing stages of the First Peloponnesian War, and the stele as an object in itself is significant.