The politics of Indonesia take place in the framework of a presidential representative democratic republic whereby the President of Indonesia is both head of state and head of government and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the bicameral People's Consultative Assembly. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.

Regime change is the partly forcible or coercive replacement of one government regime with another. Regime change may replace all or part of the state's most critical leadership system, administrative apparatus, or bureaucracy. Regime change may occur through domestic processes, such as revolution, coup, or reconstruction of government following state failure or civil war. It can also be imposed on a country by foreign actors through invasion, overt or covert interventions, or coercive diplomacy. Regime change may entail the construction of new institutions, the restoration of old institutions, and the promotion of new ideologies.

In political science, a political system means the type of political organization that can be recognized, observed or otherwise declared by a state.

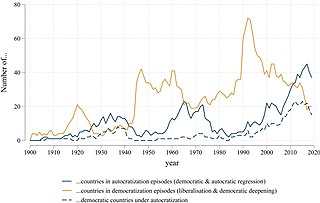

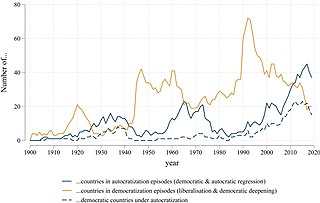

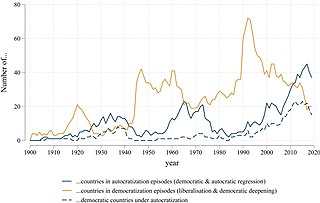

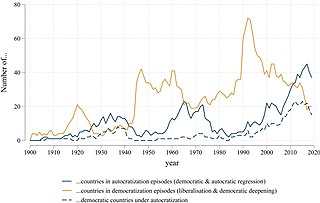

Democratization, or democratisation, is the democratic transition to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction.

The term "illiberal democracy" describes a governing system that hides its "nondemocratic practices behind formally democratic institutions and procedures". There is a lack of consensus among experts about the exact definition of illiberal democracy or whether it even exists.

The state of Democracy in Middle East and North Africa can be comparatively assessed according to various definitions of democracy. According to The Economist Group's Democracy Index 2023 study, Israel is the only democratic country in the region, qualified as a "flawed democracy". According to the V-Dem Democracy indices, the Middle Eastern and North African countries with the highest scores in 2023 are Israel, Lebanon and Iraq.

Interventionism is a political practice of intervention, particularly to the practice of governments to interfere in political affairs of other countries, staging military or trade interventions. Economic interventionism is a different practice of intervention, one of economic policy at home.

In political science and in international and comparative law and economics, transitology is the study of the process of change from one political regime to another, mainly from authoritarian regimes to democratic ones rooted in conflicting and consensual varieties of economic liberalism.

Democratic consolidation is the process by which a new democracy matures, in a way that it becomes unlikely to revert to authoritarianism without an external shock, and is regarded as the only available system of government within a country. A country can be described as consolidated when the current democratic system becomes “the only game in town”, meaning no one in the country is trying to act outside of the set institutions. This is the case when no significant political group seriously attempts to overthrow the democratic regime, the democratic system is regarded as the most appropriate way to govern by the vast majority of the public, and all political actors are accustomed to the fact that conflicts are resolved through established political and constitutional rules.

A democratic transition describes a phase in a countries political system as a result of an ongoing change from an authoritarian regime to a democratic one The process is known as democratisation, political changes moving in a democratic direction. Democratization waves have been linked to sudden shifts in the distribution of power among the great powers, which created openings and incentives to introduce sweeping domestic reforms. Although transitional regimes experience more civil unrest, they may be considered stable in a transitional phase for decades at a time. Since the end of the Cold War transitional regimes have become the most common form of government. Scholarly analysis of the decorative nature of democratic institutions concludes that the opposite democratic backsliding (autocratization), a transition to authoritarianism is the most prevalent basis of modern hybrid regimes.

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of democracy, civil liberties, and political plurality. It involves the use of strong central power to preserve the political status quo, and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic voting. Political scientists have created many typologies describing variations of authoritarian forms of government. Authoritarian regimes may be either autocratic or oligarchic and may be based upon the rule of a party or the military. States that have a blurred boundary between democracy and authoritarianism have some times been characterized as "hybrid democracies", "hybrid regimes" or "competitive authoritarian" states.

A coup d'état, or simply a coup, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is when a leader, having come to power through legal means, tries to stay in power through illegal means.

Democracy promotion by the United States aims to encourage governmental and non-governmental actors to pursue political reforms that will lead ultimately to democratic governance.

Thomas Carothers is an American lawyer and expert on international democracy support, democratization, and U.S. foreign policy. He is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where he founded and currently co-directs the Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program. He has also taught at several universities in the United States and Europe, including Central European University, the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, and Nuffield College, Oxford.

Anocracy, or semi-democracy, is a form of government that is loosely defined as part democracy and part dictatorship, or as a "regime that mixes democratic with autocratic features". Another definition classifies anocracy as "a regime that permits some means of participation through opposition group behavior but that has incomplete development of mechanisms to redress grievances." The term "semi-democratic" is reserved for stable regimes that combine democratic and authoritarian elements. Scholars distinguish anocracies from autocracies and democracies in their capability to maintain authority, political dynamics, and policy agendas. Similarly, the regimes have democratic institutions that allow for nominal amounts of competition. Such regimes are particularly susceptible to outbreaks of armed conflict and unexpected or adverse changes in leadership.

A hybrid regime is a type of political system often created as a result of an incomplete democratic transition from an authoritarian regime to a democratic one. Hybrid regimes are categorized as having a combination of autocratic features with democratic ones and can simultaneously hold political repressions and regular elections. Hybrid regimes are commonly found in developing countries with abundant natural resources such as petro-states. Although these regimes experience civil unrest, they may be relatively stable and tenacious for decades at a time. There has been a rise in hybrid regimes since the end of the Cold War.

Embedded democracy is a form of government in which democratic governance is secured by democratic partial regimes. The term "embedded democracy" was coined by political scientists Wolfgang Merkel, Hans-Jürgen Puhle, and Aurel Croissant, who identified "five interdependent partial regimes" necessary for an embedded democracy: electoral regime, political participation, civil rights, horizontal accountability, and the power of the elected representatives to govern. The five internal regimes work together to check the power of the government, while external regimes also help to secure and stabilize embedded democracies. Together, all the regimes ensure that an embedded democracy is guided by the three fundamental principles of freedom, equality, and control.

A democratic intervention is a military intervention by external forces with the aim of assisting democratization of the country where the intervention takes place. Examples include intervention in Afghanistan and Iraq. Democratic intervention has occurred throughout the mid-twentieth century, as evidenced in Japan and Germany after World War II, where democracies were imposed by military intervention.

Democratic backsliding is a process of regime change towards autocracy that makes the exercise of political power by the public more arbitrary and repressive. This process typically restricts the space for public contestation and political participation in the process of government selection. Democratic decline involves the weakening of democratic institutions, such as the peaceful transition of power or free and fair elections, or the violation of individual rights that underpin democracies, especially freedom of expression. Democratic backsliding is the opposite of democratization.

The territorial peace theory finds that the stability of a country's borders has a large influence on the political climate of the country. Peace and stable borders foster a democratic and tolerant climate, while territorial conflicts with neighbor countries have far-reaching consequences for both individual-level attitudes, government policies, conflict escalation, arms races, and war.