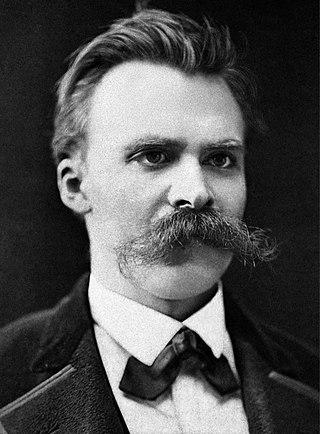

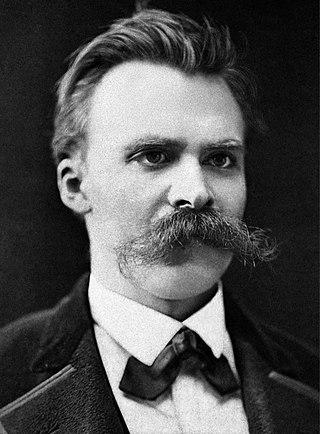

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a German classical scholar, philosopher, and critic of culture, who became one of the most influential of all modern thinkers. He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest person to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in Switzerland in 1869, at the age of 24, but resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life; he completed much of his core writing in the following decade. In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and afterward a complete loss of his mental faculties, with paralysis and probably vascular dementia. He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until her death in 1897, and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. Nietzsche died in 1900, after experiencing pneumonia and multiple strokes.

German literature comprises those literary texts written in the German language. This includes literature written in Germany, Austria, the German parts of Switzerland and Belgium, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, South Tyrol in Italy and to a lesser extent works of the German diaspora. German literature of the modern period is mostly in Standard German, but there are some currents of literature influenced to a greater or lesser degree by dialects.

In philosophy, nihilism is any viewpoint, or a family of views, that rejects generally accepted or fundamental aspects of human existence, namely knowledge, morality, or meaning. There have been different nihilist positions, including that human values are baseless, that life is meaningless, that knowledge is impossible, or that some other highly regarded concepts are in fact meaningless or pointless. The term was popularized by Ivan Turgenev and more specifically by his character Bazarov in the novel Fathers and Sons.

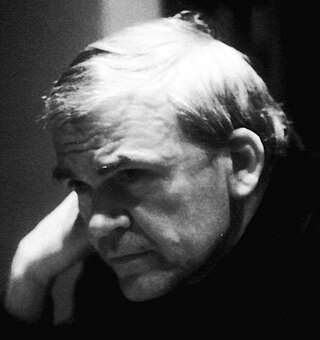

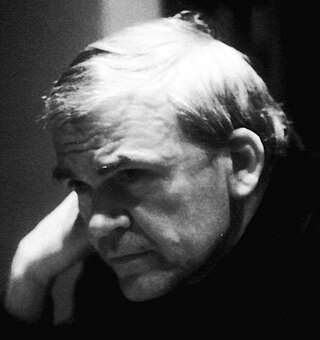

Milan Kundera was a Czech and French novelist. Kundera went into exile in France in 1975, acquiring citizenship in 1981. His Czechoslovak citizenship was revoked in 1979, but he was granted Czech citizenship in 2019.

Adalbert Stifter was a Bohemian-Austrian writer, poet, painter, and pedagogue. He was notable for the vivid natural landscapes depicted in his writing and has long been popular in the German-speaking world.

Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future is a book by philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche that covers ideas in his previous work Thus Spoke Zarathustra but with a more polemical approach. It was first published in 1886 under the publishing house C. G. Naumann of Leipzig at the author's own expense and first translated into English by Helen Zimmern, who was two years younger than Nietzsche and knew the author.

"God is dead" is a statement made by the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. The first instance of this statement in Nietzsche's writings is in his 1882 The Gay Science, where it appears three times. The phrase also appears at the beginning of Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra.

Christian Friedrich Hebbel was a German poet and dramatist.

Doctor Faustus is a German novel written by Thomas Mann, begun in 1943 and published in 1947 as Doktor Faustus: Das Leben des deutschen Tonsetzers Adrian Leverkühn, erzählt von einem Freunde.

The Biedermeier period was an era in Central Europe between 1815 and 1848 during which the middle classes grew in number and the arts began to appeal to their sensibilities. The period began with the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and ended with the onset of the Revolutions of 1848.

The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum, or: how violence develops and where it can lead is a 1974 novel by Heinrich Böll.

Austrian literature is mostly written in German, and is closely connected with German literature.

Literature of the 19th century refers to world literature produced during the 19th century. The range of years is, for the purpose of this article, literature written from (roughly) 1799 to 1900. Many of the developments in literature in this period parallel changes in the visual arts and other aspects of 19th-century culture.

Paul Ludwig Carl Heinrich Rée was a German author, physician, philosopher, and friend of Friedrich Nietzsche.

Green Henry is a partially autobiographical novel by the Swiss author Gottfried Keller, first published in 1855, and extensively revised in 1879. Truth is freely mingled with fiction, and there is a generalizing purpose to exhibit the psychic disease that affected the whole generation of the transition from romanticism to realism in life and art. The work stands with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Wilhelm Meister and Adalbert Stifter's Der Nachsommer as one of the most important examples of Bildungsromane, novels of self-development.

Indian Summer may refer to:

Egoist anarchism or anarcho-egoism, often shortened as simply egoism, is a school of anarchist thought that originated in the philosophy of Max Stirner, a 19th-century philosopher whose "name appears with familiar regularity in historically orientated surveys of anarchist thought as one of the earliest and best known exponents of individualist anarchism". Egoist anarchism places the individual at the forefront, crafting ethical standards and actions based on this premise. It advocates personal liberation and rejects subordination, emphasizing the absolute priority of self-interest.

On the Genealogy of Morality: A Polemic is an 1887 book by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. It consists of a preface and three interrelated treatises that expand and follow through on concepts Nietzsche sketched out in Beyond Good and Evil (1886). The three treatises trace episodes in the evolution of moral concepts with a view to confronting "moral prejudices", specifically those of Christianity and Judaism.

The Kefermarkt altarpiece is a richly decorated wooden altarpiece in the Late Gothic style in the parish church of Kefermarkt in Upper Austria. Commissioned by the knight Christoph von Zelking, it was completed around 1497. Saints Peter, Wolfgang and Christopher are depicted in the central section. The wing panels depict scenes from the life of Mary, and the altarpiece also has an intricate superstructure and two side figures of Saints George and Florian.

Ernst August Bertram was a German professor of German studies at the University of Cologne, but also a poet and writer who was close to the George-Kreis and the lyricist Stefan George.