A hermit, also known as an eremite or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Cenobiticmonasticism is a monastic tradition that stresses community life. Often in the West the community belongs to a religious order, and the life of the cenobitic monk is regulated by a religious rule, a collection of precepts. The older style of monasticism, to live as a hermit, is called eremitic. A third form of monasticism, found primarily in Eastern Christianity, is the skete.

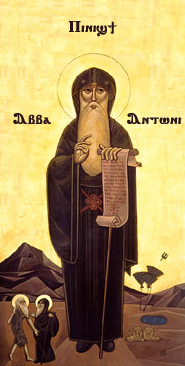

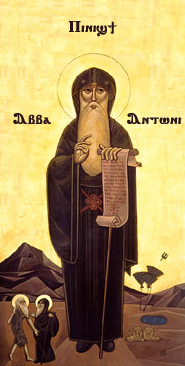

The Desert Fathers were early Christian hermits and ascetics, who lived primarily in the Scetes desert of the Roman province of Egypt, beginning around the third century AD. The Apophthegmata Patrum is a collection of the wisdom of some of the early desert monks and nuns, in print as Sayings of the Desert Fathers. The first Desert Father was Paul of Thebes, and the most well known was Anthony the Great, who moved to the desert in AD 270–271 and became known as both the father and founder of desert monasticism. By the time Anthony had died in AD 356, thousands of monks and nuns had been drawn to living in the desert following Anthony's example, leading his biographer, Athanasius of Alexandria, to write that "the desert had become a city." The Desert Fathers had a major influence on the development of Christianity.

Melania the Elder, Latin Melania Maior was a Desert Mother who was an influential figure in the Christian ascetic movement that sprang up in the generation after the Emperor Constantine made Christianity a legal religion of the Roman Empire. She was a contemporary of, and well known to, Abba Macarius and other Desert Fathers in Egypt, Jerome, Augustine of Hippo, Paulinus of Nola, and Evagrius of Pontus, and she founded two religious communities on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem. She stands out for the convent she founded for herself and the monastery she established in honour of Rufinus of Aquileia, which belongs to the earliest Christian communities, and because she promoted the asceticism which she, as a follower of Origen, considered indispensable for salvation.

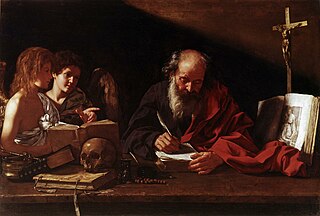

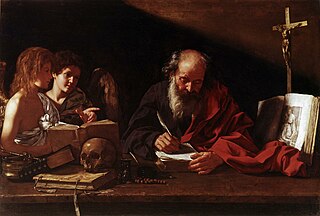

Evagrius Ponticus, also called Evagrius the Solitary, was a Christian monk and ascetic from Heraclea, a city on the coast of Bithynia in Asia Minor. One of the most influential theologians in the late fourth-century church, he was well known as a thinker, polished speaker, and gifted writer. He left a promising ecclesiastical career in Constantinople and traveled to Jerusalem, where in 383 AD he became a monk at the monastery of Rufinus and Melania the Elder. He then went to Egypt and spent the remaining years of his life in Nitria and Kellia, marked by years of asceticism and writing. He was a disciple of several influential contemporary church leaders, including Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Macarius of Egypt. He was a teacher of others, including John Cassian and Palladius of Galatia.

Monastic settlements are areas built up in and around the development of monasteries with the spread of Christianity. To understand Christian monastic settlements, we must understand a brief history of Christian monasticism. Monasticism was a movement especially associated with Early Christianity that began in the late 3rd century to the 4th century in Egypt when early Christians realizing that martyrdom wasn’t much of an option when the Roman empire relaxed Christian persecutions. It was begun by key monks who were known then as “The Desert Fathers” and later, there were female monasteries run by women who later came to be known as “The Desert Mothers”. The most famous Desert Father was Abba Anthony and the most famous Desert Mother was Amma Syncletica.ost of the Christians took to the deserts and arid areas to deny themselves of the social environments and people in order to focus on God and prayer. They denied themselves of a comfortable life often resorting to eating what grew in the deserts as well as living frugally and in poverty. With time, monasticism came to impact the church and even the papacy and there came about two variants of monasticism: The Eastern Monastic movement and the Western Monastic movement. Inspired by the Eastern monastic movements, new monastic movements sprung up in western Europe after the Roman empire fell apart and newer kingdoms like the Franks, Britannia and Germanic tribes sprung up. The papacy was at its infancy and places like the Isles of Britannia had monks that established monasteries along its coastlines. One of the forerunners was St. Augustine whose Rule became encoded in the future doctrine of the Roman clergy of the church.

A skete is a monastic community in Eastern Christianity that allows relative isolation for monks, but also allows for communal services and the safety of shared resources and protection. It is one of four types of early monastic orders, along with the eremitic, lavritic and coenobitic, that became popular during the early formation of the Christian Church.

Pambo was a Coptic Desert Father of the fourth century and disciple of Anthony the Great. His feast day is July 18 among the Oriental Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox, and Catholic churches.

The Lausiac History is a seminal work archiving the Desert Fathers written in 419–420 AD by Palladius of Galatia, at the request of Lausus, chamberlain at the court of the Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II.

The Sayings of the Desert Fathers is the name given to various textual collections consisting of stories and sayings attributed to the Desert Fathers and Desert Mothers from approximately the 5th century AD.

Abba Poemen the Great was a Christian monk and early Desert Father who is the most quoted Abba (Father) in the Apophthegmata Patrum. Abba Poemen was quoted most often for his gift as a spiritual guide, reflected in the name "Poemen" ("Shepherd"), rather than for his asceticism. He is considered a saint in Eastern Christianity. His feast day is August 27 in the Julian calendar.

Monasticism is a way of life where a person lives outside of society, under religious vows.

Syncletica of Alexandria was a Christian saint, ascetic, anchorite, and Desert Mother from Roman Egypt in the 4th century AD. She is the subject of The Life of Syncletica, a Greek hagiography purportedly by Athanasius of Alexandria but not published until 450; and the Alphabetical and Systematic Apophthegmata, which included 28 of her sayings and teachings. She died at the age of 80, after a three-year-long illness from mouth cancer.

Amma (Mother) Sarah of the Desert was one of the early Desert Mothers who is known to us today through the collected Sayings of the Desert Fathers and of the Holy Women Ascetics. She was a hermit and followed a life dedicated to strict asceticism for some sixty years.

The Asceticon by Abba Isaiah of Scetis is a diverse anthology of essays by an Egyptian Christian monk who left Scetis around 450 AD.

Apollinaris Syncletica was a saint and hermit of the 5th century, venerated in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Her story is most likely apocryphal and "turns on the familiar theme of a girl putting on male attire and living for many years undiscovered".

Stephen of Thebes was a Roman Egyptian Christian ascetic writer who flourished around AD 400. Although virtually nothing is known about his life and he is scarcely studied in recent times, his works were once widely disseminated, translated and excerpted. Originally composed in either Greek or Coptic, translations into Arabic, Ethiopic, Georgian and Old Slavonic are also known and some excerpts were translated into Armenian.

Ammonas of Egypt was an eastern Christian anchorite, monastic, and Desert Father who was born around the early 4th century. He is a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Ammonas was a disciple of Anthony the Great and Pambo. Many of his known sayings and quotations exist in eleven sections of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers.

Abba Pitirim of Porphyry or Pitirim of Egypt was an Egyptian Christian monastic and saint of the fourth century, and a disciple of Anthony the Great. His feast day is November 29 in the Orthodox Church.