Notes

This article needs additional citations for verification .(October 2019) |

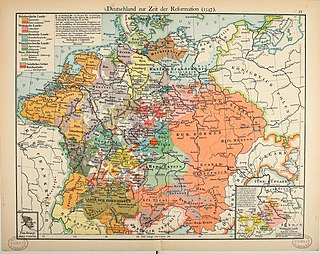

The Colloquy of Regensburg, historically called the Colloquy of Ratisbon, was a conference held at Regensburg (Ratisbon) in Bavaria in 1541, during the Protestant Reformation, which marks the culmination of attempts to restore religious unity in the Holy Roman Empire by means of theological debate between the Protestants and the Catholics.

Delegates from the various factions had met at Haguenau in 1540 and at Worms in January 1541 but the latter session of the Imperial Diet was adjourned by the Emperor Charles V as the Diet was preparing to meet at Regensburg. The subject for debate was to be the Augsburg Confession, the primary doctrinal statement of the Protestant movement, and the Apology of the Augsburg Confession, a defence of the Confession written by Philipp Melanchthon.

On 15 December 1540 a secret conference took place between Johann Gropper, canon of Cologne, and Gerhard Veltwick, the Imperial secretary, on the one side and Butzer and Capito, the delegates of Protestant Strasbourg, on the other. The two sides agreed their positions on original sin and justification, but the promise made by the Catholic party at Haguenau, to negotiate on the basis of the Confession and Apology, was withdrawn.

Early in 1541, Butzer sent a draft of the conclusions to Joachim II, Elector of Brandenburg, with the request to communicate it to Luther and the other princes of the Protestant league. The document was essentially identical with the later so-called Regensburg Book, which formed the basis of the Regensburg Conference in place of the Augsburg Confession.

It was divided into twenty-three articles, some of which closely approached the Protestant view; but it decided no questions of dogma and did not exclude the Catholic positions. On 13 February 1541 the book reached the hands of Luther. In spite of the apparent concessions made in regard to the doctrine of justification, he perceived that the proposed articles of agreement could be accepted by neither party.

On 23 February 1541 the Emperor entered Regensburg. In consideration of his difficult political situation, especially of the threatened war with the Ottoman Turks and the negotiations of the French king with the Protestants in his country, it was his desire to pacify Germany. The conference was opened on 5 April. The negotiators were Gropper, Pflug, and Eck on the Catholic side, under the oversight of the Papal Legate Cardinal Contarini; Bucer, the elder Johannes Pistorius, and Melanchthon for the Protestants. Besides the presidents, Count Palatine Frederick and Granvella, six witnesses were present, among them Burkhardt and Feige, chancellors of Saxony and Hesse respectively, and Jakob Sturm of Strasbourg.

The first four articles, on the condition and integrity of man before the fall, on free will, on the cause of sin, and on original sin, passed without difficulty. The article on justification encountered great opposition, especially from Eck, but an agreement was finally arrived at; neither Elector John Frederick nor Luther were satisfied with this article. With respect to the articles on the doctrinal authority of the Church, the hierarchy, discipline, sacraments, etc., no agreement was possible, and they were all passed over without result. On 31 May the book, with the changes agreed upon and nine counter-propositions of the Protestants, was returned to the Emperor. In spite of the opposition of Mainz, Bavaria, and the Imperial legate, Charles V still hoped for an agreement on the basis of the articles which had been accepted by both parties, those in which they differed being postponed to a later time.

As it was perceived that all negotiations would be in vain if the consent of Luther were not obtained, a deputation headed by John of Anhalt arrived at Wittenberg, where Luther resided, on 9 June. Luther answered in a polite and almost diplomatic way. He expressed satisfaction in reference to the agreement on some of the articles, but did not believe in the sincerity of his opponents and made his consent dependent upon conditions which he knew could not be accepted by the Roman Catholics.

Before the deputation had returned from Wittenberg, the Roman party had entirely destroyed all hope of union. The formula of justification, which Contarini had sent to Rome, was rejected by a papal consistory. Rome declared that the matter could be settled only at a council, and this opinion was shared by the stricter party among the estates. Albert of Mainz urged the Emperor to take up arms against the Protestants. Charles V tried in vain to induce the Protestants to accept the disputed articles, while Joachim of Brandenburg made new attempts to bring about an agreement. With every day the gulf between the opposing parties became wider, and both of them, even the Roman Catholics, showed a disposition to ally themselves with France against the Emperor.

Pope Paul III addresses the mighty Emperor of Germany, and we may properly say that Calvin, though indirectly, does the same. This strange colloquy is well worth the trouble of listening to it. The Pope:"We are desirous of the peace and the unity of Germany; but of a peace and a unity which do not constitute a perpetual war against God." Calvin:"That is to say, against the earthly god, the Roman god. For if he (the pope) wished for peace with the true God, he would live in a different manner; he would teach otherwise and reign otherwise than he does. For his whole existence, his institutions, and his decrees make war on God." The Pope: "The Protestants are like slippery snakes; they aim at no certain object, and thus show plainly enough that they are altogether enemies of concord, and want, not the suppression of vice but the overthrow of the apostolic see! We ought not to have any further negotiations with them." Calvin: "Certainly, there is a snake in the grass here. The pope, who holds in abomination all discussion, cannot hear it spoken of without immediately crying 'Fire!' in order to prevent it. Only let anyone call to mind all the little assemblies held by the pontiffs these twenty years and more, for the purpose of smothering the Gospel, and then he will see clearly what kind of a reformation they would be willing to accept. All men of sound mind see clearly the question is not only of maintaining the status of the pope as a sovereign and limited episcopacy, but rather of completely setting aside the episcopal office and of establishing in its stead and under its name an anti-Christian tyranny. And not only so, but the adherents of the papacy put men out of their minds by wicked and impious lies, and corrupt the world by numberless examples of debauchery. Not contented with these misdeeds, they exterminate those who strive to restore to the Church a purer doctrine and a more lawful order, or who merely venture to ask for these things.

— The History of the Reformation in the Time of Calvin , by J. H. Merle d'Aubigne, Vol. 7, 1877, ch. "CHAPTER XX. CALVIN AT RATISBON. (1541.)"

Thus the fate of the Regensburg Book was no longer doubtful. After Elector John Frederick and Luther had become fully acquainted with its contents, their disinclination was confirmed, and Luther demanded most decidedly that even the articles agreed upon should be rejected. On 5 July the estates rejected the Emperor's efforts for union. They demanded an investigation of the articles agreed upon, and that in case of necessity they should be amended and explained by the Papal legate. Moreover, the Protestants were to be compelled to accept the disputed articles; in case of their refusal a general or national council was to be convoked. Contarini received instructions to announce to the Emperor that all settlement of religious and ecclesiastical questions should be left to the Pope. Thus the whole effort for union was frustrated, even before the Protestant estates declared that they insisted upon their counterproposals in regard to the disputed articles.

The supposed results of the religious conference were to be laid before a general or national council or before an assembly of the Empire which was to be convoked within eighteen months. In the meantime the Protestants were bound to the Regensburg Interim, enacted by Charles V, to ensure that they adhere to the articles agreed upon, not to publish anything on them, and not to abolish any churches or monasteries, while the prelates were requested to reform their clergy at the order of the legate. The peace of Nuremberg was to extend until the time of the future council, but the Augsburg Recess was to be maintained.

These decisions might have become very dangerous to the Protestants, and in order not to force them into an alliance with his foreign opponents, the Emperor decided to change some of the resolutions in their favor; but the Roman Catholics did not acknowledge his declaration. As he was not willing to expose himself to an intervention on their part, he left Regensburg on 29 June, without having obtained either an agreement or a humiliation of the Protestants, and the Roman party now looked upon him with greater mistrust than the Protestants.

This article needs additional citations for verification .(October 2019) |

The Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent, now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation at the time, it has been described as the embodiment of the Counter-Reformation.

Gasparo Contarini was an Italian diplomat, cardinal, and Bishop of Belluno. He advocated for dialogue with Protestants during the Reformation. Born in Venice, he served as the Republic's ambassador to Charles V during its war with him. He was the first to explain the time discrepancy in the Magellan–Elcano circumnavigation due to Earth's rotation. He participated in diplomatic efforts and reconciliations, and became a cardinal, even though he was initially a layman. Contarini was a leader in the reform movement within the Roman Catholic Church. He played a role in the papal approval of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). He was also involved in attempts to restore religious unity in Germany.

George of Brandenburg-Ansbach, known as George the Pious, was a Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach from the House of Hohenzollern.

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation and the European Reformation, was a major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and the authority of the Catholic Church. Following the start of the Renaissance, the Reformation marked the beginning of Protestantism.

Pope Paul III, born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death, in November 1549.

Martin Bucer was a German Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a member of the Dominican Order, but after meeting and being influenced by Martin Luther in 1518 he arranged for his monastic vows to be annulled. He then began to work for the Reformation, with the support of Franz von Sickingen.

Cuius regio, eius religio is a Latin phrase which literally means "whose realm, their religion" – meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled. This legal principle marked a major development in the collective freedom of religion within Western civilization. Before tolerance of individual religious divergences became accepted, most statesmen and political theorists took it for granted that religious diversity weakened a state – and particularly weakened ecclesiastically-transmitted control and monitoring in a state. The principle of "cuius regio" was a compromise in the conflict between this paradigm of statecraft and the emerging trend toward religious pluralism developing throughout the German-speaking lands of the Holy Roman Empire. It permitted assortative migration of adherents to two religious groups, Roman Catholic and Lutheran, eliding other confessions.

Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, nicknamed der Großmütige, was a German nobleman and champion of the Protestant Reformation, notable for being one of the most important of the early Protestant rulers in Germany.

In the scholastic system of education of the Middle Ages, disputations offered a formalized method of debate designed to uncover and establish truths in theology and in sciences. Fixed rules governed the process: they demanded dependence on traditional written authorities and the thorough understanding of each argument on each side.

Crypto-Calvinism is a pejorative term describing a segment of those members of the Lutheran Church in Germany who were accused of secretly subscribing to Calvinist doctrine of the Eucharist in the decades immediately after the death of Martin Luther in 1546. It denotes what was seen as a hidden Calvinist belief, i.e., the doctrines of John Calvin, by members of the Lutheran Church. The term crypto-Calvinist in Lutheranism was preceded by terms Zwinglian and Sacramentarian. Also, Jansenism has been accused of crypto-Calvinism by Roman Catholics.

The diets of Augsburg were the meetings of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in the German city of Augsburg. Both an Imperial City and the residence of the Augsburg prince-bishops, the town had hosted the Estates in many such sessions since the 10th century. In 1282, the diet of Augsburg assigned the control of Austria to the House of Habsburg. In the 16th century, twelve of thirty-five imperial diets were held in Augsburg, a result of the close financial relationship between the Augsburg-based banking families such as the Fugger and the reigning Habsburg emperors, particularly Maximilian I and his grandson Charles V. Nevertheless, the meetings of 1518, 1530, 1547/48 and 1555, during the Reformation and the ensuing religious war between the Catholic emperor and the Protestant Schmalkaldic League, are especially noteworthy. With the Peace of Augsburg, the cuius regio, eius religio principle let each prince decide the religion of his subjects and inhabitants who could not conform could leave.

John Frederick I, called the Magnanimous, was the Elector of Saxony (1532–1547) and head of the Schmalkaldic League.

The Augsburg Interim was an imperial decree ordered on 15 May 1548 at the 1548 Diet of Augsburg by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, who had just defeated the forces of the Protestant Schmalkaldic League in the Schmalkaldic War of 1546/47. Although it ordered Protestants to readopt traditional Catholic beliefs and practices, including the seven Sacraments, it allowed for Protestant clergymen the right to marry and for the laity to receive communion in both kinds. It is considered the first significant step in the process leading to the political and religious legitimization of Protestantism as a valid alternative Christian creed to Roman Catholicism finally realized in the 1552 Peace of Passau and the 1555 Peace of Augsburg. The Interim became Imperial law on 30 June 1548. The Pope advised all bishops to abide by the concessions made to the Protestants in the Interim in August 1549.

Johann Gropper was a German cardinal and church politician of the Reformation period.

Lutheranism as a religious movement originated in the early 16th century Holy Roman Empire as an attempt to reform the Roman Catholic Church. The movement originated with the call for a public debate regarding several issues within the Catholic Church by Martin Luther, then a professor of Bible at the young University of Wittenberg. Lutheranism soon became a wider religious and political movement within the Holy Roman Empire owing to support from key electors and the widespread adoption of the printing press. This movement soon spread throughout northern Europe and became the driving force behind the wider Protestant Reformation. Today, Lutheranism has spread from Europe to all six populated continents.

The Regensburg Interim, traditionally called in English the Interim of Ratisbon, was a temporary settlement in matters of religion, entered into by Emperor Charles V with the Protestants in 1541.

In 16th-century Christianity, Protestantism came to the forefront and marked a significant change in the Christian world.

The Augsburg Confession, also known as the Augustan Confession or the Augustana from its Latin name, Confessio Augustana, is the primary confession of faith of the Lutheran Church and one of the most important documents of the Reformation. The Augsburg Confession was written in both German and Latin and was presented by a number of German rulers and free-cities at the Diet of Augsburg on 25 June 1530.

The term Protestant ecclesiology refers to the spectrum of teachings held by the Protestant Reformers concerning the nature and mystery of the invisible church that is known in Protestantism as the Christian Church.

Catholic–Protestant relations refers to the social, political and theological relations and dialogue between the Catholics and Protestants.