Related Research Articles

Atomic physics is the field of physics that studies atoms as an isolated system of electrons and an atomic nucleus. Atomic physics typically refers to the study of atomic structure and the interaction between atoms. It is primarily concerned with the way in which electrons are arranged around the nucleus and the processes by which these arrangements change. This comprises ions, neutral atoms and, unless otherwise stated, it can be assumed that the term atom includes ions.

In modern physics, antimatter is defined as matter composed of the antiparticles of the corresponding particles in "ordinary" matter, and can be thought of as matter with reversed charge, parity, and time, known as CPT reversal. Antimatter occurs in natural processes like cosmic ray collisions and some types of radioactive decay, but only a tiny fraction of these have successfully been bound together in experiments to form antiatoms. Minuscule numbers of antiparticles can be generated at particle accelerators; however, total artificial production has been only a few nanograms. No macroscopic amount of antimatter has ever been assembled due to the extreme cost and difficulty of production and handling. Nonetheless, antimatter is an essential component of widely-available applications related to beta decay, such as positron emission tomography, radiation therapy, and industrial imaging.

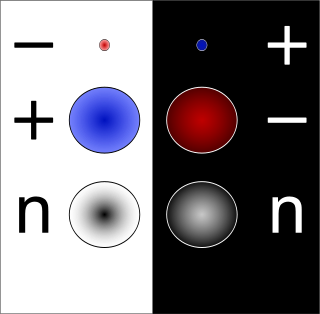

In particle physics, every type of particle of "ordinary" matter is associated with an antiparticle with the same mass but with opposite physical charges. For example, the antiparticle of the electron is the positron. While the electron has a negative electric charge, the positron has a positive electric charge, and is produced naturally in certain types of radioactive decay. The opposite is also true: the antiparticle of the positron is the electron.

The electron is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family, and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no known components or substructure. The electron's mass is approximately 1/1836 that of the proton. Quantum mechanical properties of the electron include an intrinsic angular momentum (spin) of a half-integer value, expressed in units of the reduced Planck constant, ħ. Being fermions, no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state, per the Pauli exclusion principle. Like all elementary particles, electrons exhibit properties of both particles and waves: They can collide with other particles and can be diffracted like light. The wave properties of electrons are easier to observe with experiments than those of other particles like neutrons and protons because electrons have a lower mass and hence a longer de Broglie wavelength for a given energy.

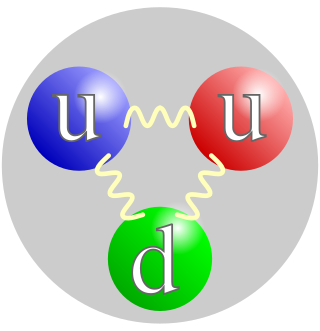

In particle physics, an elementary particle or fundamental particle is a subatomic particle that is not composed of other particles. The Standard Model presently recognizes seventeen distinct particles—twelve fermions and five bosons. As a consequence of flavor and color combinations and antimatter, the fermions and bosons are known to have 48 and 13 variations, respectively. Among the 61 elementary particles embraced by the Standard Model number: electrons and other leptons, quarks, and the fundamental bosons. Subatomic particles such as protons or neutrons, which contain two or more elementary particles, are known as composite particles.

Particle physics or high-energy physics is the study of fundamental particles and forces that constitute matter and radiation. The field also studies combinations of elementary particles up to the scale of protons and neutrons, while the study of combination of protons and neutrons is called nuclear physics.

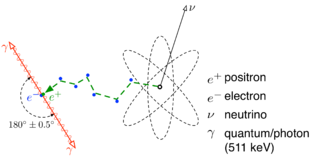

The positron or antielectron is the particle with an electric charge of +1e, a spin of 1/2, and the same mass as an electron. It is the antiparticle of the electron. When a positron collides with an electron, annihilation occurs. If this collision occurs at low energies, it results in the production of two or more photons.

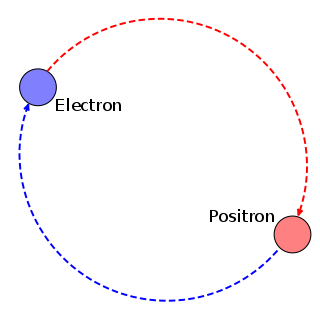

Positronium (Ps) is a system consisting of an electron and its anti-particle, a positron, bound together into an exotic atom, specifically an onium. Unlike hydrogen, the system has no protons. The system is unstable: the two particles annihilate each other to predominantly produce two or three gamma-rays, depending on the relative spin states. The energy levels of the two particles are similar to that of the hydrogen atom. However, because of the reduced mass, the frequencies of the spectral lines are less than half of those for the corresponding hydrogen lines.

A timeline of atomic and subatomic physics.

Electron–positron annihilation occurs when an electron and a positron collide. At low energies, the result of the collision is the annihilation of the electron and positron, and the creation of energetic photons:

Pair production is the creation of a subatomic particle and its antiparticle from a neutral boson. Examples include creating an electron and a positron, a muon and an antimuon, or a proton and an antiproton. Pair production often refers specifically to a photon creating an electron–positron pair near a nucleus. As energy must be conserved, for pair production to occur, the incoming energy of the photon must be above a threshold of at least the total rest mass energy of the two particles created. Conservation of energy and momentum are the principal constraints on the process. All other conserved quantum numbers of the produced particles must sum to zero – thus the created particles shall have opposite values of each other. For instance, if one particle has electric charge of +1 the other must have electric charge of −1, or if one particle has strangeness of +1 then another one must have strangeness of −1.

In physics, a subatomic particle is a particle smaller than an atom. According to the Standard Model of particle physics, a subatomic particle can be either a composite particle, which is composed of other particles, or an elementary particle, which is not composed of other particles. Particle physics and nuclear physics study these particles and how they interact. Most force carrying particles like photons or gluons are called bosons and, although they have discrete quanta of energy, do not have rest mass or discrete diameters and are unlike the former particles that have rest mass and cannot overlap or combine which are called fermions.

The Dirac sea is a theoretical model of the electron vacuum as an infinite sea of electrons with negative energy, now called positrons. It was first postulated by the British physicist Paul Dirac in 1930 to explain the anomalous negative-energy quantum states predicted by the Dirac equation for relativistic electrons. The positron, the antimatter counterpart of the electron, was originally conceived of as a hole in the Dirac sea, before its experimental discovery in 1932.

In particle physics, annihilation is the process that occurs when a subatomic particle collides with its respective antiparticle to produce other particles, such as an electron colliding with a positron to produce two photons. The total energy and momentum of the initial pair are conserved in the process and distributed among a set of other particles in the final state. Antiparticles have exactly opposite additive quantum numbers from particles, so the sums of all quantum numbers of such an original pair are zero. Hence, any set of particles may be produced whose total quantum numbers are also zero as long as conservation of energy, conservation of momentum, and conservation of spin are obeyed.

Quantum mechanics is the study of matter and its interactions with energy on the scale of atomic and subatomic particles. By contrast, classical physics explains matter and energy only on a scale familiar to human experience, including the behavior of astronomical bodies such as the moon. Classical physics is still used in much of modern science and technology. However, towards the end of the 19th century, scientists discovered phenomena in both the large (macro) and the small (micro) worlds that classical physics could not explain. The desire to resolve inconsistencies between observed phenomena and classical theory led to a revolution in physics, a shift in the original scientific paradigm: the development of quantum mechanics.

The gravitational interaction of antimatter with matter or antimatter has been observed by physicists. As was the consensus among physicists previously, it was experimentally confirmed that gravity attracts both matter and antimatter at the same rate within experimental error.

Asım Orhan Barut was a Turkish-American theoretical physicist.

The Breit–Wheeler process or Breit–Wheeler pair production is a proposed physical process in which a positron–electron pair is created from the collision of two photons. It is the simplest mechanism by which pure light can be potentially transformed into matter. The process can take the form γ γ′ → e+ e− where γ and γ′ are two light quanta.

Negative energy is a concept used in physics to explain the nature of certain fields, including the gravitational field and various quantum field effects.

References

- ↑ Gottfried, Kurt (2011). "P. A. M. Dirac and the discovery of quantum mechanics". pubs.aip.org. Retrieved 2023-10-23.

- ↑ "Dirac hole theory". McGraw-Hill Dictionary of Scientific & Technical Terms. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ↑ Jim Branson. "Negative Energy Solutions: Hole Theory". University of California, San Diego . Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- 1 2 Kragh, Helge (1990). Dirac: A Scientific Biography . Cambridge University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0521380898.

- ↑ Martin, Brian Robert; Shaw, Graham (2008). "Hole theory and the positron". Particle physics (3rd ed.). Chichester, UK: ProQuest (published 2008-11-20). p. 6. ISBN 9780470032947.