Related Research Articles

Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that can hold information temporarily. It is important for reasoning and the guidance of decision-making and behavior. Working memory is often used synonymously with short-term memory, but some theorists consider the two forms of memory distinct, assuming that working memory allows for the manipulation of stored information, whereas short-term memory only refers to the short-term storage of information. Working memory is a theoretical concept central to cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and neuroscience.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by executive dysfunction occasioning symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity and emotional dysregulation that are excessive and pervasive, impairing in multiple contexts, and otherwise age-inappropriate.

Attention is the concentration of awareness on some phenomenon to the exclusion of other stimuli. It is a process of selectively concentrating on a discrete aspect of information, whether considered subjective or objective. William James (1890) wrote that "Attention is the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration, of consciousness are of its essence." Attention has also been described as the allocation of limited cognitive processing resources. Attention is manifested by an attentional bottleneck, in terms of the amount of data the brain can process each second; for example, in human vision, only less than 1% of the visual input data can enter the bottleneck, leading to inattentional blindness.

Dopaminergic pathways in the human brain are involved in both physiological and behavioral processes including movement, cognition, executive functions, reward, motivation, and neuroendocrine control. Each pathway is a set of projection neurons, consisting of individual dopaminergic neurons.

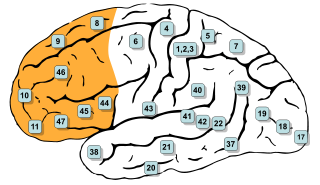

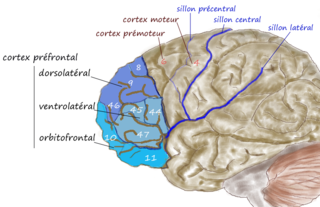

In mammalian brain anatomy, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) covers the front part of the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex. It is the association cortex in the frontal lobe. The PFC contains the Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA11, BA12, BA13, BA14, BA24, BA25, BA32, BA44, BA45, BA46, and BA47.

Sensory overload occurs when one or more of the body's senses experiences over-stimulation from the environment.

Affective neuroscience is the study of how the brain processes emotions. This field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood. The basis of emotions and what emotions are remains an issue of debate within the field of affective neuroscience.

In cognitive science and neuropsychology, executive functions are a set of cognitive processes that are necessary for the cognitive control of behavior: selecting and successfully monitoring behaviors that facilitate the attainment of chosen goals. Executive functions include basic cognitive processes such as attentional control, cognitive inhibition, inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Higher-order executive functions require the simultaneous use of multiple basic executive functions and include planning and fluid intelligence.

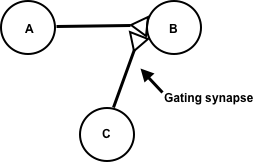

Synaptic gating is the ability of neural circuits to gate inputs by either suppressing or facilitating specific synaptic activity. Selective inhibition of certain synapses has been studied thoroughly, and recent studies have supported the existence of permissively gated synaptic transmission. In general, synaptic gating involves a mechanism of central control over neuronal output. It includes a sort of gatekeeper neuron, which has the ability to influence transmission of information to selected targets independently of the parts of the synapse upon which it exerts its action.

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is an area in the prefrontal cortex of the primate brain. It is one of the most recently derived parts of the human brain. It undergoes a prolonged period of maturation which lasts into adulthood. The DLPFC is not an anatomical structure, but rather a functional one. It lies in the middle frontal gyrus of humans. In macaque monkeys, it is around the principal sulcus. Other sources consider that DLPFC is attributed anatomically to BA 9 and 46 and BA 8, 9 and 10.

In psychology, impulsivity is a tendency to act on a whim, displaying behavior characterized by little or no forethought, reflection, or consideration of the consequences. Impulsive actions are typically "poorly conceived, prematurely expressed, unduly risky, or inappropriate to the situation that often result in undesirable consequences," which imperil long-term goals and strategies for success. Impulsivity can be classified as a multifactorial construct. A functional variety of impulsivity has also been suggested, which involves action without much forethought in appropriate situations that can and does result in desirable consequences. "When such actions have positive outcomes, they tend not to be seen as signs of impulsivity, but as indicators of boldness, quickness, spontaneity, courageousness, or unconventionality." Thus, the construct of impulsivity includes at least two independent components: first, acting without an appropriate amount of deliberation, which may or may not be functional; and second, choosing short-term gains over long-term ones.

In psychology and neuroscience, executive dysfunction, or executive function deficit, is a disruption to the efficacy of the executive functions, which is a group of cognitive processes that regulate, control, and manage other cognitive processes. Executive dysfunction can refer to both neurocognitive deficits and behavioural symptoms. It is implicated in numerous psychopathologies and mental disorders, as well as short-term and long-term changes in non-clinical executive control. Executive dysfunction is the mechanism underlying ADHD Paralysis, and in a broader context, it can encompass other cognitive difficulties like planning, organizing, initiating tasks and regulating emotions. It is a core characteristic of ADHD and can elucidate numerous other recognized symptoms.

Attention restoration theory (ART) asserts that people can concentrate better after spending time in nature, or even looking at scenes of nature. Natural environments abound with "soft fascinations" which a person can reflect upon in "effortless attention", such as clouds moving across the sky, leaves rustling in a breeze or water bubbling over rocks in a stream. Philosophically, nature has long been seen as a source of peace and energy, yet the scientific community started rigorous testing only as recently as the 1990s which has allowed scientific and accurate comments to be made about if nature has a restorative attribute.

Inhibitory control, also known as response inhibition, is a cognitive process – and, more specifically, an executive function – that permits an individual to inhibit their impulses and natural, habitual, or dominant behavioral responses to stimuli in order to select a more appropriate behavior that is consistent with completing their goals. Self-control is an important aspect of inhibitory control. For example, successfully suppressing the natural behavioral response to eat cake when one is craving it while dieting requires the use of inhibitory control.

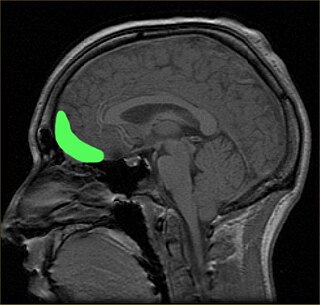

Attentional control, colloquially referred to as concentration, refers to an individual's capacity to choose what they pay attention to and what they ignore. It is also known as endogenous attention or executive attention. In lay terms, attentional control can be described as an individual's ability to concentrate. Primarily mediated by the frontal areas of the brain including the anterior cingulate cortex, attentional control and attentional shifting are thought to be closely related to other executive functions such as working memory.

Cognitive inhibition refers to the mind's ability to tune out stimuli that are irrelevant to the task/process at hand or to the mind's current state. Additionally, it can be done either in whole or in part, intentionally or otherwise. Cognitive inhibition in particular can be observed in many instances throughout specific areas of cognitive science.

Hypofrontality is a state of decreased cerebral blood flow (CBF) in the prefrontal cortex of the brain. Hypofrontality is symptomatic of several neurological medical conditions, such as schizophrenia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. This condition was initially described by Ingvar and Franzén in 1974, through the use of xenon blood flow technique with 32 detectors to image the brains of patients with schizophrenia. This finding was confirmed in subsequent studies using the improved spatial resolution of positron emission tomography with the fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) tracer. Subsequent neuroimaging work has shown that the decreases in prefrontal CBF are localized to the medial, lateral, and orbital portions of the prefrontal cortex. Hypofrontality is thought to contribute to the negative symptoms of schizophrenia.

Mindfulness has been defined in modern psychological terms as "paying attention to relevant aspects of experience in a nonjudgmental manner", and maintaining attention on present moment experience with an attitude of openness and acceptance. Meditation is a platform used to achieve mindfulness. Both practices, mindfulness and meditation, have been "directly inspired from the Buddhist tradition" and have been widely promoted by Jon Kabat-Zinn. Mindfulness meditation has been shown to have a positive impact on several psychiatric problems such as depression and therefore has formed the basis of mindfulness programs such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based pain management. The applications of mindfulness meditation are well established, however the mechanisms that underlie this practice are yet to be fully understood. Many tests and studies on soldiers with PTSD have shown tremendous positive results in decreasing stress levels and being able to cope with problems of the past, paving the way for more tests and studies to normalize and accept mindful based meditation and research, not only for soldiers with PTSD, but numerous mental inabilities or disabilities.

Social cognitive neuroscience is the scientific study of the biological processes underpinning social cognition. Specifically, it uses the tools of neuroscience to study "the mental mechanisms that create, frame, regulate, and respond to our experience of the social world". Social cognitive neuroscience uses the epistemological foundations of cognitive neuroscience, and is closely related to social neuroscience. Social cognitive neuroscience employs human neuroimaging, typically using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Human brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation are also used. In nonhuman animals, direct electrophysiological recordings and electrical stimulation of single cells and neuronal populations are utilized for investigating lower-level social cognitive processes.

Affect labeling is an implicit emotional regulation strategy that can be simply described as "putting feelings into words". Specifically, it refers to the idea that explicitly labeling one's, typically negative, emotional state results in a reduction of the conscious experience, physiological response, and/or behavior resulting from that emotional state. For example, writing about a negative experience in one's journal may improve one's mood. Some other examples of affect labeling include discussing one's feelings with a therapist, complaining to friends about a negative experience, posting one's feelings on social media or acknowledging the scary aspects of a situation.

References

- ↑ Itti L, Geraint R, Tsotsos JK, eds. (2005). Neurobiology of Attention. Boston: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-375731-9. OCLC 58724292.

- ↑ Beadle S. "Directed Attention Fatigue and Restoration". Troutfoot.com. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ↑ Lin H, Saunders B, Friese M, Evans NJ, Inzlicht M (May 2020). "Strong Effort Manipulations Reduce Response Caution: A Preregistered Reinvention of the Ego-Depletion Paradigm". Psychological Science. 31 (5): 531–547. doi:10.1177/0956797620904990. PMC 7238509 . PMID 32315259.

- ↑ Kaplan S, Berman MG (January 2010). "Directed Attention as a Common Resource for Executive Functioning and Self-Regulation". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 5 (1): 43–57. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.589.9322 . doi:10.1177/1745691609356784. PMID 26162062. S2CID 4992335.

- ↑ Glosser G, Goodglass H (August 1990). "Disorders in executive control functions among aphasic and other brain-damaged patients". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 12 (4): 485–501. doi:10.1080/01688639008400995. PMID 1698809.

- ↑ Kuo FE, Taylor AF (September 2004). "A potential natural treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence from a national study". American Journal of Public Health. 94 (9): 1580–1586. doi:10.2105/ajph.94.9.1580. PMC 1448497 . PMID 15333318.

- 1 2 Weissinger, Kristen M. (December 2016). Nature-based experiences and mobile phones: a pilot study on the effects of text notifications on attention restoration (PDF) (Master of Science thesis). The University of Utah Graduate School. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- 1 2 Ricci, JA; Chee, E; Lorandeau, AL; Berger, J (January 2007). "Fatigue in the U.S. workforce: prevalence and implications for lost productive work time". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 49 (1): 1–10 [9]. doi:10.1097/01.jom.0000249782.60321.2a. PMID 17215708 . Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ↑ Lorist, Monicque M.; Boksem, Maarten A. S.; Ridderinkhof, K. Richard (July 2005). "Impaired cognitive control and reduced cingulate activity during mental fatigue". Brain Research. Cognitive Brain Research. 24 (2): 199–205. doi:10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.01.018. ISSN 0926-6410. PMID 15993758 . Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ↑ Mesulam, M.-Marsel (January 1983). "The functional anatomy and hemispheric specialization for directed attention". Trends in Neurosciences. 6: 384–387. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(83)90171-6.

- ↑ Jaffe E (May 2010). "This side of paradise: discovering why the human mind needs nature". Observer. 23 (5).

- ↑ Posner MI, Sheese BE, Odludaş Y, Tang Y (November 2006). "Analyzing and shaping human attentional networks". Neural Networks. 19 (9): 1422–1429. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2006.08.004. PMID 17059879.

- ↑ Dodds CM, Morein-Zamir S, Robbins TW (May 2011). "Dissociating inhibition, attention, and response control in the frontoparietal network using functional magnetic resonance imaging". Cerebral Cortex. 21 (5): 1155–1165. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhq187. PMC 3077432 . PMID 20923963.

- ↑ Pfaff DW, Kieffer BL, eds. (2008). Molecular and Biophysical Mechanisms of Arousal, Alertness, and Attention. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. Vol. 1129. Boston: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57331-703-0. OCLC 229430529.

- ↑ Kaplan R, Kaplan S (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-34939-0. OCLC 18814094.

- ↑ "Directed attention fatigue". Bio-Medicine. Archived from the original on 2011-09-14. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Kaplan S (July 2001). "Meditation, restoration, and the management of mental fatigue". Environment and Behavior. 33 (4): 480–506. Bibcode:2001EnvBe..33..480K. doi:10.1177/00139160121973106. S2CID 7194754.

- ↑ Stevenson, MP; Schilhab, T; Bentsen, P (2018). "Attention Restoration Theory II: a systematic review to clarify attention processes affected by exposure to natural environments". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health. Part B, Critical Reviews. 21 (4): 227–268. Bibcode:2018JTEHB..21..227S. doi:10.1080/10937404.2018.1505571. PMID 30130463 . Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- 1 2 Lofy J (Fall 2006). "A Walk in the Woods". Michigan Today. Archived from the original on 2011-03-12. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. (1989). The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-34139-4.

- ↑ Nauert R (17 November 2010). "Brain fatigue from living in the city?". PsychCentral. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- ↑ Kuo FE. "Current Research". Landscape and Human Health Laboratory. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on 3 April 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ Taylor, AF; Kuo, FE (March 2009). "Children with attention deficits concentrate better after walk in the park". Journal of Attention Disorders. 12 (5): 402–409. doi:10.1177/1087054708323000. PMID 18725656 . Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- 1 2 Sun, H; Soh, KG; Roslan, S; Wazir, MRWN; Mohammadi, A; Ding, C; Zhao, Z (2022). "Nature exposure might be the intervention to improve the self-regulation and skilled performance in mentally fatigue athletes: A narrative review and conceptual framework". Frontiers in Psychology. 13: 941299. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.941299 . PMC 9378859 . PMID 35983203.