The Children's Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 (COPPA) is a United States federal law, located at 15 U.S.C. §§ 6501–6506.

Internet privacy involves the right or mandate of personal privacy concerning the storage, re-purposing, provision to third parties, and display of information pertaining to oneself via the Internet. Internet privacy is a subset of data privacy. Privacy concerns have been articulated from the beginnings of large-scale computer sharing and especially relate to mass surveillance.

A privacy policy is a statement or legal document that discloses some or all of the ways a party gathers, uses, discloses, and manages a customer or client's data. Personal information can be anything that can be used to identify an individual, not limited to the person's name, address, date of birth, marital status, contact information, ID issue, and expiry date, financial records, credit information, medical history, where one travels, and intentions to acquire goods and services. In the case of a business, it is often a statement that declares a party's policy on how it collects, stores, and releases personal information it collects. It informs the client what specific information is collected, and whether it is kept confidential, shared with partners, or sold to other firms or enterprises. Privacy policies typically represent a broader, more generalized treatment, as opposed to data use statements, which tend to be more detailed and specific.

The Video Privacy Protection Act (VPPA) is a bill that was passed by the United States Congress in 1988 as Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law (United States) 100–618 and signed into law by President Ronald Reagan. It was created to prevent what it refers to as "wrongful disclosure of video tape rental or sale records" or similar audio visual materials, to cover items such as video games. Congress passed the VPPA after Robert Bork's video rental history was published during his Supreme Court nomination and it became known as the "Bork bill". It makes any "video tape service provider" that discloses rental information outside the ordinary course of business liable for up to $2,500 in actual damages unless the consumer has consented, the consumer had the opportunity to consent, or the data was subject to a court order or warrant.

The Platform for Privacy Preferences Project (P3P) is an obsolete protocol allowing websites to declare their intended use of information they collect about web browser users. Designed to give users more control of their personal information when browsing, P3P was developed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and officially recommended on April 16, 2002. Development ceased shortly thereafter and there have been very few implementations of P3P. Internet Explorer and Microsoft Edge were the only major browsers to support P3P. Microsoft has ended support from Windows 10 onwards. Internet Explorer and Edge on Windows 10 no longer support P3P. The president of TRUSTe has stated that P3P has not been implemented widely due to the difficulty and lack of value.

A local shared object (LSO), commonly called a Flash cookie, is a piece of data that websites that use Adobe Flash may store on a user's computer. Local shared objects have been used by all versions of Flash Player since version 6.

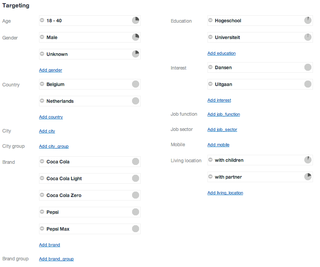

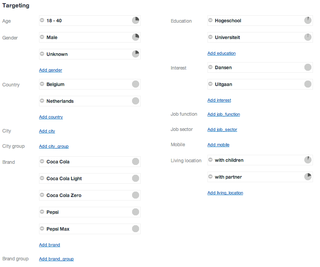

Targeted advertising is a form of advertising, including online advertising, that is directed towards an audience with certain traits, based on the product or person the advertiser is promoting.

Web tracking is the practice by which operators of websites and third parties collect, store and share information about visitors’ activities on the World Wide Web. Analysis of a user's behaviour may be used to provide content that enables the operator to infer their preferences and may be of interest to various parties, such as advertisers. Web tracking can be part of visitor management.

The Network Advertising Initiative is an industry trade group founded in 2000 that develops self-regulatory standards for online advertising. Advertising networks created the organization in response to concerns from the Federal Trade Commission and consumer groups that online advertising — particularly targeted or behavioral advertising — harmed user privacy. The NAI seeks to provide self-regulatory guidelines for participating networks and opt-out technologies for consumers in order to maintain the value of online advertising while protecting consumer privacy. Membership in the NAI has fluctuated greatly over time, and both the organization and its self-regulatory system have been criticized for being ineffective in promoting privacy.

The United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has been involved in oversight of the behavioral targeting techniques used by online advertisers since the mid-1990s. These techniques, initially called "online profiling", are now referred to as "behavioral targeting"; they are used to target online behavioral advertising (OBA) to consumers based on preferences inferred from their online behavior. During the period from the mid-1990s to the present, the FTC held a series of workshops, published a number of reports, and gave numerous recommendations regarding both industry self-regulation and Federal regulation of OBA. In late 2010, the FTC proposed a legislative framework for U.S. consumer data privacy including a proposal for a "Do Not Track" mechanism. In 2011, a number of bills were introduced into the United States Congress that would regulate OBA.

In the middle of 2009 the Federal Trade Commission filed a complaint against Sears Holdings Management Corporation (SHMC) for unfair or deceptive acts or practices affecting commerce. SHMC operates the sears.com and kmart.com retail websites for Sears Holdings Corporation. As part of a marketing effort, some users of sears.com and kmart.com were invited to download an application developed for SHMC that ran in the background on users' computers collecting information on nearly all internet activity. The tracking aspects of the program were only disclosed in legalese in the middle of the End User License Agreement. The FTC found this was insufficient disclosure given consumers expectations and the detailed information being collected. On September 9, 2009 the FTC approved a consent decree with SHMC requiring full disclosure of its activities and destruction of previously obtained information.

Web browsing history refers to the list of web pages a user has visited, as well as associated metadata such as page title and time of visit. It is usually stored locally by web browsers in order to provide the user with a history list to go back to previously visited pages. It can reflect the user's interests, needs, and browsing habits.

Do Not Track (DNT) is a formerly official HTTP header field, designed to allow internet users to opt-out of tracking by websites—which includes the collection of data regarding a user's activity across multiple distinct contexts, and the retention, use, or sharing of data derived from that activity outside the context in which it occurred.

Since the arrival of early social networking sites in the early 2000s, online social networking platforms have expanded exponentially, with the biggest names in social media in the mid-2010s being Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat. The massive influx of personal information that has become available online and stored in the cloud has put user privacy at the forefront of discussion regarding the database's ability to safely store such personal information. The extent to which users and social media platform administrators can access user profiles has become a new topic of ethical consideration, and the legality, awareness, and boundaries of subsequent privacy violations are critical concerns in advance of the technological age.

Chris Jay Hoofnagle is an American professor at the University of California, Berkeley who teaches information privacy law, computer crime law, regulation of online privacy, internet law, and seminars on new technology. Hoofnagle has contributed to the privacy literature by writing privacy law legal reviews and conducting research on the privacy preferences of Americans. Notably, his research demonstrates that most Americans prefer not to be targeted online for advertising and despite claims to the contrary, young people care about privacy and take actions to protect it. Hoofnagle has written scholarly articles regarding identity theft, consumer privacy, U.S. and European privacy laws, and privacy policy suggestions.

United States v. Google Inc., No. 3:12-cv-04177, is a case in which the United States District Court for the Northern District of California approved a stipulated order for a permanent injunction and a $22.5 million civil penalty judgment, the largest civil penalty the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has ever won in history. The FTC and Google Inc. consented to the entry of the stipulated order to resolve the dispute which arose from Google's violation of its privacy policy. In this case, the FTC found Google liable for misrepresenting "privacy assurances to users of Apple's Safari Internet browser". It was reached after the FTC considered that through the placement of advertising tracking cookies in the Safari web browser, and while serving targeted advertisements, Google violated the 2011 FTC's administrative order issued in FTC v. Google Inc.

Google's changes to its privacy policy on March 16, 2012, enabled the company to share data across a wide variety of services. These embedded services include millions of third-party websites that use AdSense and Analytics. The policy was widely criticized for creating an environment that discourages Internet innovation by making Internet users more fearful and wary of what they do online.

Cross-device tracking is technology that enables the tracking of users across multiple devices such as smartphones, television sets, smart TVs, and personal computers.

On 28 March 2017, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution of disapproval to overturn the Broadband Consumer Privacy Proposal privacy law by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and was expected to be approved by United States' President Donald Trump. It was passed with 215 Republican votes against 205 votes of disapproval.

The gathering of personally identifiable information (PII) is the practice of collecting public and private personal data that can be used to identify an individual for both legal and illegal applications. PII owners often view PII gathering as a threat and violation of their privacy. Meanwhile, entities such as information technology companies, governments, and organizations use PII for data analysis of consumer shopping behaviors, political preference, and personal interests.