Related Research Articles

Atracidae is a family of mygalomorph spiders, commonly known as Australian funnel-web spiders or atracids. It has been included as a subfamily of the Hexathelidae, but is now recognized as a separate family. All members of the family are native to Australia. Atracidae consists of three genera: Atrax, Hadronyche, and Illawarra, comprising 35 species. Some members of the family produce venom that is dangerous to humans, and bites by spiders of six of the species have caused severe injuries to victims. The bites of the Sydney funnel-web spider and northern tree-dwelling funnel-web spider are potentially deadly, but no fatalities have occurred since the introduction of modern first-aid techniques and antivenom.

Antivenom, also known as antivenin, venom antiserum, and antivenom immunoglobulin, is a specific treatment for envenomation. It is composed of antibodies and used to treat certain venomous bites and stings. Antivenoms are recommended only if there is significant toxicity or a high risk of toxicity. The specific antivenom needed depends on the species involved. It is given by injection.

Mambas are fast-moving, highly venomous snakes of the genus Dendroaspis in the family Elapidae. Four extant species are recognised currently; three of those four species are essentially arboreal and green in colour, whereas the black mamba, Dendroaspis polylepis, is largely terrestrial and generally brown or grey in colour. All are native to various regions in sub-Saharan Africa and all are feared throughout their ranges, especially the black mamba. In Africa there are many legends and stories about mambas.

A snakebite is an injury caused by the bite of a snake, especially a venomous snake. A common sign of a bite from a venomous snake is the presence of two puncture wounds from the animal's fangs. Sometimes venom injection from the bite may occur. This may result in redness, swelling, and severe pain at the area, which may take up to an hour to appear. Vomiting, blurred vision, tingling of the limbs, and sweating may result. Most bites are on the hands, arms, or legs. Fear following a bite is common with symptoms of a racing heart and feeling faint. The venom may cause bleeding, kidney failure, a severe allergic reaction, tissue death around the bite, or breathing problems. Bites may result in the loss of a limb or other chronic problems or even death.

Snake venom is a highly toxic saliva containing zootoxins that facilitates in the immobilization and digestion of prey. This also provides defense against threats. Snake venom is injected by unique fangs during a bite, whereas some species are also able to spit venom.

The boomslang is a large, highly venomous snake in the family Colubridae.

Envenomation is the process by which venom is injected by the bite or sting of a venomous animal.

The black mamba is a species of highly venomous snake belonging to the family Elapidae. It is native to parts of sub-Saharan Africa. First formally described by Albert Günther in 1864, it is the second-longest venomous snake after the king cobra; mature specimens generally exceed 2 m and commonly grow to 3 m (9.8 ft). Specimens of 4.3 to 4.5 m have been reported. Its skin colour varies from grey to dark brown. Juvenile black mambas tend to be paler than adults and darken with age.

The Indian cobra, also known commonly as the spectacled cobra, Asian cobra, or binocellate cobra, is a species of cobra, a venomous snake in the family Elapidae. The species is native to India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bhutan, and is a member of the "big four" species that are responsible for the most snakebite cases in India.

Rhabdophis subminiatus, commonly called the red-necked keelback or red-necked keelback snake, is a species of venomous snake in the subfamily Natricinae of the family Colubridae. The species is endemic to Asia.

The Caspian cobra, also called the Central Asian cobra, ladle snake, Oxus cobra, or Russian cobra, is a species of venomous snake in the family Elapidae. The species is endemic to Central Asia. Described by Karl Eichwald in 1831, it was for many years considered a subspecies of the Indian cobra until genetic analysis revealed it to be a distinct species.

A spider bite, also known as arachnidism, is an injury resulting from the bite of a spider. The effects of most bites are not serious. Most bites result in mild symptoms around the area of the bite. Rarely they may produce a necrotic skin wound or severe pain.

Naja is a genus of venomous elapid snakes commonly known as cobras. Members of the genus Naja are the most widespread and the most widely recognized as "true" cobras. Various species occur in regions throughout Africa, Southwest Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Several other elapid species are also called "cobras", such as the king cobra and the rinkhals, but neither is a true cobra, in that they do not belong to the genus Naja, but instead each belong to monotypic genera Hemachatus and Ophiophagus.

The king brown snake is a species of highly venomous snake of the family Elapidae, native to northern, western, and Central Australia. Despite its common name, it is a member of the genus Pseudechis and only distantly related to true brown snakes. Its alternative common name is the mulga snake, although it lives in many habitats apart from mulga. First described by English zoologist John Edward Gray in 1842, it is a robust snake up to 3.3 m (11 ft) long. It is variable in appearance, with individuals from northern Australia having tan upper parts, while those from southern Australia are dark brown to blackish. Sometimes, it is seen in a reddish-green texture. The dorsal scales are two-toned, sometimes giving the snake a patterned appearance. Its underside is cream or white, often with orange splotches. The species is oviparous. The snake is considered to be a least-concern species according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, though may have declined with the spread of the cane toad.

Venomous fish are species of fish which produce strong mixtures of toxins harmful to humans which they deliberately deliver by means of a bite, sting, or stab, resulting in an envenomation. As a contrast, poisonous fish also produce a strong toxin, but they do not bite, sting, or stab to deliver the toxin, instead being poisonous to eat because the human digestive system does not destroy the toxin they contain in their bodies. Venomous fish do not necessarily cause poisoning if they are eaten, as the digestive system often destroys the venom.

Jameson's mamba is a species of highly venomous snake native to equatorial Africa. A member of the mamba genus, Dendroaspis, it is slender with dull green upper parts and cream underparts and generally ranges from 1.5 to 2.2 m in length. Described by Scottish naturalist Thomas Traill in 1843, it has two recognised subspecies: the nominate subspecies from central and west sub-Saharan Africa and the eastern black-tailed subspecies from eastern sub-Saharan Africa, mainly western Kenya.

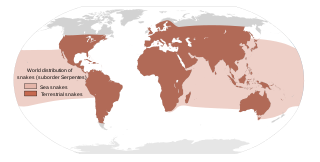

Most snakebites are caused by non-venomous snakes. Of the roughly 3,700 known species of snake found worldwide, only 15% are considered dangerous to humans. Snakes are found on every continent except Antarctica. There are two major families of venomous snakes, Elapidae and Viperidae. 325 species in 61 genera are recognized in the family Elapidae and 224 species in 22 genera are recognized in the family Viperidae, In addition, the most diverse and widely distributed snake family, the colubrids, has approximately 700 venomous species, but only five genera—boomslangs, twig snakes, keelback snakes, green snakes, and slender snakes—have caused human fatalities.

The pathophysiology of a spider bite is due to the effect of its venom. A spider envenomation occurs whenever a spider injects venom into the skin. Not all spider bites inject venom – a dry bite, and the amount of venom injected can vary based on the type of spider and the circumstances of the encounter. The mechanical injury from a spider bite is not a serious concern for humans. Some spider bites do leave a large enough wound that infection may be a concern. However, it is generally the toxicity of spider venom that poses the most risk to human beings; several spiders are known to have venom that can cause injury to humans in the amounts that a spider will typically inject when biting.

References

- ↑ Silveira, PV; Nishioka Sde A (1995). "Venomous snake bite without clinical envenoming ('dry-bite'). A neglected problem in Brazil". Trop Geogr Med. 47 (2): 82–85. PMID 8592769.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Pucca, Manuela B.; Knudsen, Cecilie; S Oliveira, Isadora; Rimbault, Charlotte; A Cerni, Felipe; Wen, Fan Hui; Sachett, Jacqueline; Sartim, Marco A.; Laustsen, Andreas H.; Monteiro, Wuelton M. (2020-10-22). "Current Knowledge on Snake Dry Bites". Toxins. 12 (11): 668. doi: 10.3390/toxins12110668 . ISSN 2072-6651. PMC 7690386 . PMID 33105644.

- ↑ Dart, Richard C. (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1551. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ↑ Thygerson, Alton L.; American College of Emergency Physicians, Emergency Care and Safety Institute (2006). First Aid, CPR, and AED (5th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 120. ISBN 978-0-7637-4225-6.

- ↑ Schultz, Stanley A.; Marguerite J. Schultz (1998). The Tarantula Keeper's Guide. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 978-0-7641-0076-5.