Anna Howard Shaw was a leader of the women's suffrage movement in the United States. She was also a physician and one of the first ordained female Methodist ministers in the United States.

The Women's Tax Resistance League (WTRL) was from 1909 to 1918 a direct action group associated with the Women's Freedom League that used tax resistance to protest against the disenfranchisement of women during the British women's suffrage movement.

Helen Augusta Howard was an American suffragist and philanthropist. Howard was born in Columbus, Georgia, and was one of the founding members of the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA).

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

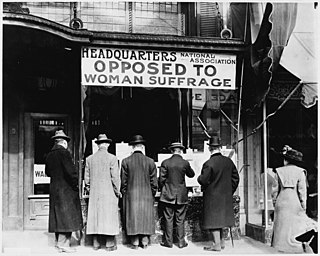

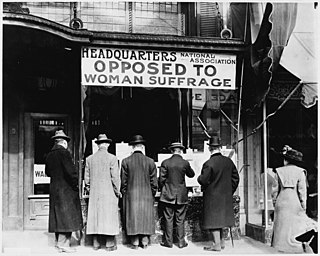

The National Association Opposed to Women Suffrage (NAOWS) was founded in the United States by women opposed to the suffrage movement in 1911. It was the most popular anti-suffrage organization in northeastern cities. NAOWS had influential local chapters in many states, including Texas and Virginia.

Lucy Elmina Anthony was an internationally known leader in the American woman's suffrage movement. She was the niece of American social reformer and women's rights activist, Susan B. Anthony, and longtime companion of women's suffrage leader, Anna Howard Shaw. She served as a secretary to both women, as well as on the committee on local arrangements for the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA)

Henrietta Haynie Maddox was a vocalist, lawyer and suffragist. Maddox became the first woman in Maryland licensed to practice law in 1902. She fought for the rights of women to take the bar exam and practice law in the state of Maryland. She was a successful vocalist who studied at the Peabody Conservatory of Music before starting a second career as an attorney. She was the co-founder of the Maryland Woman Suffrage Association in 1894 and campaigned for equal pay for equal work. Maddox wrote the first Maryland suffrage bill introduced to the General Assembly on February 23, 1910.

The Suffrage Special was an event created by the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage in 1916. The Suffrage Special toured the "free states" which had already allowed women's suffrage in the United States. The delegates were raising awareness of the national women's suffrage amendment. They were also looking to start a new political party, the National Women's Party (NWP). The Suffrage Special, also known as the "flying squadron" left Washington, D.C. and toured the Western states by train for 38 days starting on April 9, 1916. Famous and well-known suffragists made up the envoy of the Suffrage Special. They toured several states during their journey and were largely well-received. When the tour was over, the delegates of the Suffrage Special visited Congress where they presented petitions for women's suffrage they had collected on their journey.

Women's suffrage in Texas was a long term fight starting in 1868 at the first Texas Constitutional Convention. In both Constitutional Conventions and subsequent legislative sessions, efforts to provide women the right to vote were introduced, only to be defeated. Early Texas suffragists such as Martha Goodwin Tunstall and Mariana Thompson Folsom worked with national suffrage groups in the 1870s and 1880s. It wasn't until 1893 and the creation of the Texas Equal Rights Association (TERA) by Rebecca Henry Hayes of Galveston that Texas had a statewide women's suffrage organization. Members of TERA lobbied politicians and political party conventions on women's suffrage. Due to an eventual lack of interest and funding, TERA was inactive by 1898. In 1903, women's suffrage organizing was revived by Annette Finnigan and her sisters. These women created the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) in Houston in 1903. TESA sponsored women's suffrage speakers and testified on women's suffrage in front of the Texas Legislature. In 1908 and 1912, speaking tours by Anna Howard Shaw helped further renew interest in women's suffrage in Texas. TESA grew in size and suffragists organized more public events, including Suffrage Day at the Texas State Fair. By 1915, more and more women in Texas were supporting women's suffrage. The Texas Federation of Women's Clubs officially supported women's suffrage in 1915. Also that year, anti-suffrage opponents started to speak out against women's suffrage and in 1916, organized the Texas Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (TAOWS). TESA, under the political leadership of Minnie Fisher Cunningham and with the support of Governor William P. Hobby, suffragists began to make further gains in achieving their goals. In 1918, women achieved the right to vote in Texas primary elections. During the registration drive, 386,000 Texas women signed up during a 17-day period. An attempt to modify the Texas Constitution by voter referendum failed in May 1919, but in June 1919, the United States Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment. Texas became the ninth state and the first Southern state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment on June 28, 1919. This allowed white women to vote, but African American women still had trouble voting, with many turned away, depending on their communities. In 1923, Texas created white primaries, excluding all Black people from voting in the primary elections. The white primaries were overturned in 1944 and in 1964, Texas's poll tax was abolished. In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed, promising that all people in Texas had the right to vote, regardless of race or gender.

Frances Borgia Jolliffe was an American actress, journalist, and suffragist, and arts editor at the San Francisco Evening Bulletin.

Attempts to achieve women's suffrage in Montana started while Montana was still a territory. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was an early organizer that supported suffrage in the state, arriving in 1883. Women were given the right to vote in school board elections and on tax issues in 1887. When the state constitutional convention was held in 1889, Clara McAdow and Perry McAdow invited suffragist, Henry Blackwell, to speak to the delegates about equal women's suffrage. While that proposition did not pass, women retained their right to vote in school and tax elections as Montana became a state. In 1895, National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) came to Montana to organize local groups. Montana suffragists held a convention and created the Montana Woman's Suffrage Association (MWSA). Suffragists continued to organize, hold conventions and lobby the Montana Legislature for women's suffrage through the end of the nineteenth century. In the early twentieth century, Jeannette Rankin became a driving force around the women's suffrage movement in Montana. By January 1913, a women's suffrage bill had passed the Montana Legislature and went out as a referendum. Suffragists launched an all-out campaign leading up to the vote. They traveled throughout Montana giving speeches and holding rallies. They sent out thousands of letters and printed thousands of pamphlets and journals to hand out. Suffragists set up booths at the Montana State Fair and they held parades. Finally, after a somewhat contested election on November 3, 1914, the suffragists won the vote. Montana became one of eleven states with equal suffrage for most women. When the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, Montana ratified it on August 2, 1919. It wasn't until 1924 with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act that Native American women gained the right to vote.

Women's suffrage in Georgia received a slow start, with the first women's suffrage group, the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA) formed in 1892 by Helen Augusta Howard. Over time, the group, which focused on "taxation without representation" grew and earned the support of both men and women. Howard convinced the National American Women's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) to hold their first convention outside of Washington, D. C. in 1895. The convention, held in Atlanta, was the first large women's rights gathering in the Southern United States. GWSA continued to hold conventions and raise awareness over the next years. Suffragists in Georgia agitated for suffrage amendments, for political parties to support white women's suffrage and for municipal suffrage. In the 1910s, more organizations were formed in Georgia and the number of suffragists grew. In addition, the Georgia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage also formed an organized anti-suffrage campaign. Suffragists participated in parades, supported bills in the legislature and helped in the war effort during World War I. In 1917 and 1919, women earned the right to vote in primary elections in Waycross, Georgia and in Atlanta respectively. In 1919, after the Nineteenth Amendment went out to the states for ratification, Georgia became the first state to reject the amendment. When the Nineteenth Amendment became the law of the land, women still had to wait to vote because of rules regarding voter registration. White Georgia women would vote statewide in 1922. Native American women and African-American women had to wait longer to vote. Black women were actively excluded from the women's suffrage movement in the state and had their own organizations. Despite their work to vote, Black women faced discrimination at the polls in many different forms. Georgia finally ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on February 20, 1970.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Georgia. Women's suffrage in Georgia started in earnest with the formation of the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA) in 1892. GWSA helped bring the first large women's rights convention to the South in 1895 when the National American Woman's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) held their convention in Atlanta. GWSA was the main source of activism behind women's suffrage until 1913. In that year, several other groups formed including the Georgia Young People's Suffrage Association (GYPSA) and the Georgia Men's League for Woman Suffrage. In 1914, the Georgia Association Opposed to Women's Suffrage (GAOWS) was formed by anti-suffragists. Despite the hard work by suffragists in Georgia, the state continued to reject most efforts to pass equal suffrage. In 1917, Waycross, Georgia allowed women to vote in primary elections and in 1919 Atlanta granted the same. Georgia was the first state to reject the Nineteenth Amendment. Women in Georgia still had to wait to vote statewide after the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified on August 26, 1920. Native American and African American women had to wait even longer to vote. Georgia ratified the Nineteenth Amendment in 1970.

Attempts to secure women's suffrage in Wisconsin began before the Civil War. In 1846, the first state constitutional convention delegates for Wisconsin discussed women's suffrage and the final document eventually included a number of progressive measures. This constitution was rejected and a more conservative document was eventually adopted. Wisconsin newspapers supported women's suffrage and Mathilde Franziska Anneke published the German language women's rights newspaper, Die Deutsche Frauen-Zeitung, in Milwaukee in 1852. Before the war, many women's rights petitions were circulated and there was tentative work in forming suffrage organizations. After the Civil War, the first women's suffrage conference held in Wisconsin took place in October 1867 in Janesville. That year, a women's suffrage amendment passed in the state legislature and waited to pass the second year. However, in 1868 the bill did not pass again. The Wisconsin Woman Suffrage Association (WWSA) was reformed in 1869 and by the next year, there were several chapters arranged throughout Wisconsin. In 1884, suffragists won a brief victory when the state legislature passed a law to allow women to vote in elections on school-related issues. On the first voting day for women in 1887, the state Attorney General made it more difficult for women to vote and confusion about the law led to court challenges. Eventually, it was decided that without separate ballots, women could not be allowed to vote. Women would not vote again in Wisconsin until 1902 after separate school-related ballots were created. In the 1900s, state suffragists organized and continued to petition the Wisconsin legislature on women's suffrage. By 1911, two women's suffrage groups operated in the state: WWSA and the Political Equality League (PEL). A voter referendum went to the public in 1912. Both WWSA and PEL campaigned hard for women's equal suffrage rights. Despite the work put in by the suffragists, the measure failed to pass. PEL and WWSA merged again in 1913 and women continued their education work and lobbying. By 1915, the National Woman's Party also had chapters in Wisconsin and several prominent suffragists joined their ranks. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was also very present in Wisconsin suffrage efforts. Carrie Chapman Catt worked hard to keep Wisconsin suffragists on the path of supporting a federal woman's suffrage amendment. When the Nineteenth Amendment went out to the states for ratification, Wisconsin an hour behind Illinois on June 10, 1919. However, Wisconsin was the first to turn in the ratification paperwork to the State Department.

Women's suffrage in Pennsylvania was an outgrowth of the abolitionist movement in the state. Early women's suffrage advocates in Pennsylvania not only wanted equal suffrage for white women, but for all African Americans. The first women's rights convention in the state was organized by Quakers and held in Chester County in 1852. Philadelphia would host the fifth National Women's Rights Convention in 1854. Later years saw suffragists forming a statewide group, the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association (PWSA), and other smaller groups throughout the state. Early efforts moved slowly, but steadily, with suffragists raising awareness and winning endorsements from labor unions.

Mary Clare Laurence Brassington was an American suffragist, president of the Delaware Equal Suffrage Association (DESA) from 1915 to 1917.

Suffrage in New Jersey was available to most women and African Americans immediately upon the formation of the state. The first New Jersey state constitution allowed any person who owned a certain value of property to become a voter. In 1790, the state constitution was changed to specify that voters were "he or she." Politicians seeking office deliberately courted women voters who often decided narrow elections. Due to women's influence as swing voters, they were used as scapegoats to blame for election losses.

The Suffrage Torch was a wooden and bronze-finished sculpture of a torch that was used in the New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania women's suffrage campaigns starting in the summer of 1915. The torch was the idea of Harriot Stanton Blatch who wanted a visual publicity stunt to draw attention to the suffrage campaigns. The torch traveled throughout New York state and was handed over to Mina Van Winkle, head of the New Jersey suffragists. The torch was stolen in New Jersey and later recovered in Philadelphia. The suffrage torch drew a good deal of publicity during its use in the campaigns taking place in those three states.

Josephine Day Bennett was an American activist and suffragist from Connecticut. She was a member of the National Women's Party (NWP) and campaigned for women's suffrage outside of the White House, leading to her arrest. Bennett was also involved in other social issues and was supportive of striking workers.

Emily Pierson was an American suffragist and physician. Early in her career, Pierson worked as a teacher, and then later, as an organizer for the Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA). After women earned the right to vote, she went back to school to become a physician in her hometown of Cromwell, Connecticut. During much of her life, she was interested in socialism, studying and observing in both Russia and China.