The Edictum Rothari (lit. Edict of Rothari; also Edictus Rothari or Edictum Rotharis) was the first written compilation of Lombard law, codified and promulgated on 22 November 643 by King Rothari in Pavia by a gairethinx, an assembly of the army. [1] According to Paul the Deacon, the 8th century Lombard historian, the custom law of the Lombards (Lombardic: cawarfidae) had been held in memory before this. The Edict, recorded in Vulgar Latin, comprised primarily the Germanic custom law of the Lombards, with some modifications to limit the power of feudal rulers and strengthen the authority of the king. Although the edict has been drafted in Latin, a few Lombard words were left untranslated, such as "grabworfin, arga, sculdhais, morgingab, metfio, federfio, mahrworfin, launegild, thinx, waregang, gastald, mundius, angargathung, fara, walupaus, gairethinx, aldius, actugild or, wegworin".

Contents

The Edict, divided into 388 chapters, was primitive in comparison to other Germanic legislation of the time. It was also comparatively late, for the Franks, Visigoths, and Anglo-Saxons had all compiled codices of law long before. Unlike the 6th century Breviarium Alaricianum of Visigoth king Alaric II, the Edict was mostly Germanic tribal law dealing with weregilds, inheritance, and duels, not a code of Roman law. In spite of its Latin language, it was not a Roman product, and unlike the near-contemporary Forum Iudicum of the Visigoths, it was not influenced by Canon law. Its only dealing with ecclesial matters was a prohibition on violence in churches. The Edict gives military authority to the dukes and gives civil authority to a schulthais (or reeve) in the countryside and a castaldus (or gastald) in cities.

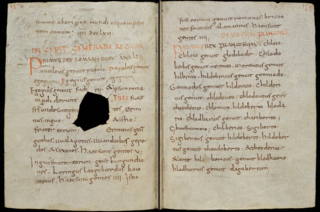

Rothari could name his lineage back to eleven generations, and wrote it down in the preamble, as shown in the full text of the edict hereby cited. [2]

It was written down by one Ansoald, a scribe of Lombard origin, and was affirmed by a gairethinx convened by Rothari in 643. The gairethinx was a gathering of the army that passed the law by clashing their spears on their shields in old Germanic fashion, a fitting passing for a Latin code that was so Germanic.

The Edict makes no references to public life, the governance of trade or the duties of a citizen; instead, it is minutely concerned with compensations for wrongs, a feature familiar from the weregild system of Anglo-Saxons and the defence of property rights. Though Lombard women were always in some status of wardship to the males of the family—and a freeborn Lombard woman who married an aldius (semi-free man) or a slave might be slain or sold by her male kin—the respect, amounting to a taboo, that was owed to a freeborn Lombard woman was notable. Anyone who would "place himself in the way" (injure) of a free woman or girl must pay 900 solidi, an immense sum. For comparison, anyone who would "place himself in the way" of a free man had to pay him 20 solidi if there was no bodily injury, and in similar cases involving another man's slave, handmaid or aldius, 20 solidi to the lord had to be paid as the price for copulation with another man's slave. Roman slaves were of lower value in these matters compared to Germanic slaves.

Physical injuries were all minutely catalogued, with a price set for damage done to each tooth, finger or toe. Property was a concern: many laws in the Edict dealt specifically with injuries to an aldius or to a household slave. A still lower class, according to their assigned values, were the agricultural slaves.

In the laws pertaining to inheritance, illegitimate offspring had rights as well as legitimate ones. No father could disinherit his son except for certain grievous crimes. Donations of property were made in the presence of an assembly called the thinc, which gave rise to the barbarous Latin verb thingare, to grant or donate before witnesses. If a man wishes to thingare his property, he must make the gairethinx ("spear donation") in the presence of free men.

Slaves might be emancipated in various ways, but there were severe laws for the pursuit and restoration of fugitives. In judicial procedure, a system of compurgation prevailed, as well as the wager of battle. The general assembly of free men continued to add ritual solemnity to important acts such as the enactment of new laws or the selection of a king.

Lombard law applied to Lombards solely. The Roman population ruled by the Lombard aristocracy expected to live under long-codified Roman law. The Edict stipulated that foreigners who came to settle in Lombard territories were expected to live according to the laws of the Lombards unless they obtained from the king the right to live according to some other law.

Later, by the reign of King Liutprand (712–743), most inhabitants of Lombard Italy were considered Lombards regardless of their ancestry and followed Lombard Law.