Radio astronomy is a subfield of astronomy that studies celestial objects at radio frequencies. The first detection of radio waves from an astronomical object was in 1933, when Karl Jansky at Bell Telephone Laboratories reported radiation coming from the Milky Way. Subsequent observations have identified a number of different sources of radio emission. These include stars and galaxies, as well as entirely new classes of objects, such as radio galaxies, quasars, pulsars, and masers. The discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation, regarded as evidence for the Big Bang theory, was made through radio astronomy.

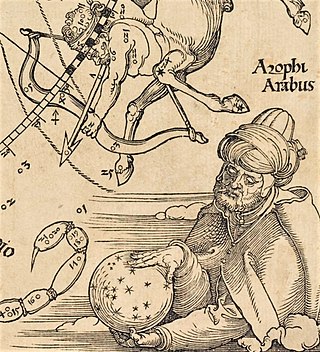

ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Ṣūfī was an Iranian astronomer. His work Kitāb ṣuwar al-kawākib, written in 964, included both textual descriptions and illustrations. The Persian polymath Al-Biruni wrote that al-Ṣūfī's work on the ecliptic was carried out in Shiraz. Al-Ṣūfī lived at the Buyid court in Isfahan.

Colleen Margaretta McCullough was an Australian author known for her novels, her most well-known being The Thorn Birds and The Ladies of Missalonghi.

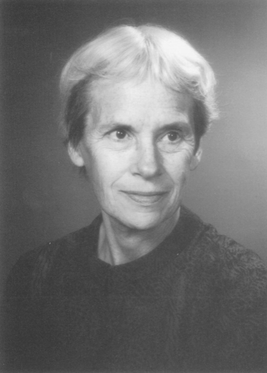

Dame Susan Jocelyn Bell Burnell is an astrophysicist from Northern Ireland who, as a postgraduate student, discovered the first radio pulsars in 1967. The discovery eventually earned the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1974; however, she was not one of the prize's recipients.

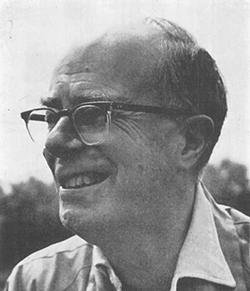

David Lambert Lack FRS was a British evolutionary biologist who made contributions to ornithology, ecology, and ethology. His 1947 book, Darwin's Finches, on the finches of the Galapagos Islands was a landmark work as were his other popular science books on Life of the Robin and Swifts in a Tower. He developed what is now known as Lack's Principle which explained the evolution of avian clutch sizes in terms of individual selection as opposed to the competing contemporary idea that they had evolved for the benefit of species. His pioneering life-history studies of the living bird helped in changing the nature of ornithology from what was then a collection-oriented field. He was a longtime director of the Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology at the University of Oxford.

Ruby Violet Payne-Scott was an Australian pioneer in radiophysics and radio astronomy, and was one of two Antipodean women pioneers in radio astronomy and radio physics at the end of the second world war, Ruby Payne-Scott the Australian and Elizabeth Alexander the New Zealander.

Dorothy Hill, was an Australian geologist and palaeontologist, the first female professor at an Australian university, and the first female president of the Australian Academy of Science.

Nancy Grace Roman was an American astronomer who made important contributions to stellar classification and motions. The first female executive at NASA, Roman served as NASA's first Chief of Astronomy throughout the 1960s and 1970s, establishing her as one of the "visionary founders of the US civilian space program".

Sir Alexander Oppenheim, OBE, PMN, FRSE was a British mathematician and university administrator. In Diophantine approximation and the theory of quadratic forms, he proposed the Oppenheim conjecture.

Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill was an English medical doctor, naturalist, ornithologist and curator of Singapore’s Raffles Museum.

Janet Vida Watson FRS FGS (1923–1985) was a British geologist. She was a professor of Geology at Imperial College, a rapporteur for the International Geological Correlation Program (IGCP) (1977–1982) and a vice president of the Royal Society (1983–1984). In 1982 she was elected president of the Geological Society of London, the first woman to occupy that position. She is well known for her contribution to the understanding of the Lewisian complex and as an author and co-author of several books including Beginning Geology and Introduction to Geology.

Sir Norman Stanley Alexander was a New Zealand physicist instrumental in the establishment of many Commonwealth universities, including Ahmadu Bello University in Nigeria, and the Universities of the West Indies, the South Pacific and Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland. He was knighted in 1966.

Sarah Salmond was a notable New Zealand governess and astronomer.

Elsa Beatrice Kidson was a New Zealand soil scientist and sculptor.

Emily Stewart Lakdawalla is an American planetary geologist and former Senior Editor of The Planetary Society, contributing as both a science writer and a blogger. She has also worked as a teacher and as an environmental consultant. She has performed research work in geology, Mars topography, and science communication and education. Lakdawalla is a science advocate on various social media platforms, interacting with space professionals and enthusiasts on Facebook, Google+ and Twitter. She has appeared on such media outlets as NPR, BBC and BBC America.

Marjorie Chandler (1897–1983) was a British paleobotanist who made her own reputation as a scientist after a long partnership with Eleanor Mary Reid, as a research assistant.

This is a timeline of women in science, spanning from ancient history up to the 21st century. While the timeline primarily focuses on women involved with natural sciences such as astronomy, biology, chemistry and physics, it also includes women from the social sciences and the formal sciences, as well as notable science educators and medical scientists. The chronological events listed in the timeline relate to both scientific achievements and gender equality within the sciences.

Andrea Dutton, a 2019 MacArthur Fellow, is a Professor of Geology in the Department of Geoscience at the University of Wisconsin–Madison where she studies paleoclimate, sedimentology, carbonate geochemistry, and paleo-oceanography. Her research centers on sea level changes during interglacial periods to predict future sea level rise.

Elizabeth Alice Flint was a New Zealand botanist who specialised in freshwater algae. She co-authored the three-volume series Flora of New Zealand Desmids in the 1980s and 1990s.

Sir George Vance Allen was an Anglo-Irish British medical doctor, bacteriologist and academic administrator who served as the first Vice-Chancellor of the University of Malaya.