The slave narrative is a type of literary genre involving the (written) autobiographical accounts of enslaved persons, particularly Africans enslaved in the Americas, though many other examples exist. Over six thousand such narratives are estimated to exist; about 150 narratives were published as separate books or pamphlets. In the United States during the Great Depression (1930s), more than 2,300 additional oral histories on life during slavery were collected by writers sponsored and published by the Works Progress Administration, a New Deal program. Most of the 26 audio-recorded interviews are held by the Library of Congress.

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States of America from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing.

The Pearl incident was the largest recorded nonviolent escape attempt by enslaved people in United States history. On April 15, 1848, seventy-seven slaves attempted to escape Washington D.C. by sailing away on a schooner called The Pearl. Their plan was to sail south on the Potomac River, then north up the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware River to the free state of New Jersey, a distance of nearly 225 miles (362 km). The attempt was organized by both abolitionist whites and free blacks, who expanded the plan to include many more enslaved people. Paul Jennings, a former slave who had served President James Madison, helped plan the escape.

African-American history started with the arrival of Africans to North America in the 16th and 17th centuries. Former Spanish slaves who had been freed by Francis Drake arrived aboard the Golden Hind at New Albion in California in 1579. The European colonization of the Americas, and the resulting Atlantic slave trade, led to a large-scale transportation of enslaved Africans across the Atlantic; of the roughly 10–12 million Africans who were sold by the Barbary slave trade, either to European slavery or to servitude in the Americas, approximately 388,000 landed in North America. After arriving in various European colonies in North America, the enslaved Africans were sold to white colonists, primarily to work on cash crop plantations. A group of enslaved Africans arrived in the English Virginia Colony in 1619, marking the beginning of slavery in the colonial history of the United States; by 1776, roughly 20% of the British North American population was of African descent, both free and enslaved.

The internal slave trade in the United States, also known as the domestic slave trade, the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the mercantile trade of enslaved people within the United States. It was most significant after 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was prohibited by federal law. Historians estimate that upwards of one million slaves were forcibly relocated from the Upper South, places like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri, to the territories and then-new states of the Deep South, especially Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

Compensated emancipation was a method of ending slavery, under which the enslaved person's owner received compensation from the government in exchange for manumitting the slave. This could be monetary, and it could allow the owner to retain the slave for a period of labor as an indentured servant. Cash compensation rarely was equal to the slave's market value.

The history of George Washington and slavery reflects Washington's changing attitude toward the ownership of human beings. The preeminent Founding Father of the United States and a hereditary slaveowner, Washington became increasingly uneasy with it. Slavery was then a longstanding institution dating back over a century in Virginia where he lived; it was also longstanding in other American colonies and in world history. Washington's will immediately freed one of his slaves, and required his remaining 123 slaves to serve his wife and be freed no later than her death, so they ultimately became free one year after his own death.

The institution of slavery in North America existed from the earliest years of the colonial history of the United States until 1865 when the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery throughout the United States except as punishment for a crime. It was also abolished among the sovereign Indian tribes in Indian Territory by new peace treaties which the US required after the Civil War.

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley was an American seamstress, activist, and writer who lived in Washington, D.C. She was the personal dressmaker and confidante of Mary Todd Lincoln. She wrote an autobiography.

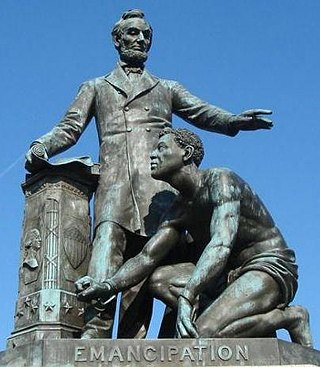

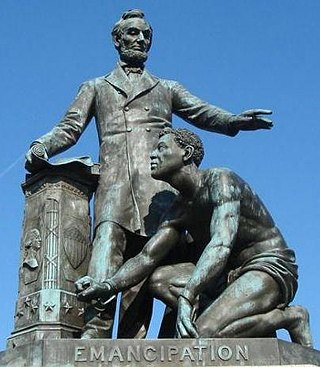

The Emancipation Memorial, also known as the Freedman's Memorial or the Emancipation Group is a monument in Lincoln Park in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, D.C. It was sometimes referred to as the "Lincoln Memorial" before the more prominent national memorial was dedicated in 1922.

The African-American upper class, sometimes referred to as the black upper class, the black upper middle class or black elite, is a social class that consists of African-American individuals who have high disposable incomes and high net worth. The group includes highly paid white-collar professionals such as academics, engineers, lawyers, accountants, doctors, politicians, business executives, venture capitalists, CEOs, celebrities, entertainers, entrepreneurs and heirs.

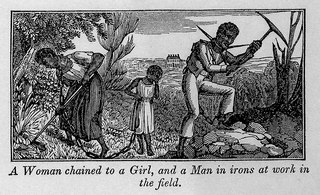

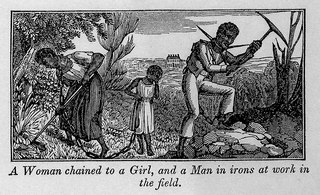

The treatment of slaves in the United States often included sexual abuse and rape, the denial of education, and punishments like whippings. Families were often split up by the sale of one or more members, usually never to see or hear of each other again.

The Association of Black Women Historians (ABWH) is a non-profit professional association based in Washington, D.C., in the United States. The organization was developed in 1977 and formally founded in 1979.

The Black Women Oral History Project consists of interviews with 72 African American women from 1976 to 1981, conducted under the auspices of the Schlesinger Library of Radcliffe College, now Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

Letitia Woods Brown was an American researcher and historian. Earning a master's degree in 1935 from Ohio State University, she served as a researcher and historian for over four decades and became one of the first black women to earn a PhD in history from Harvard University.

Michael G. Shiner was an African-American Navy Yard worker and diarist who chronicled events in Washington D.C. for more than 60 years, first as a slave and later as a free man. His diary is the earliest-known by an African American resident of the District of Columbia. The diary has numerous entries which have provided historians a firsthand account of the War of 1812, the British Invasion of Washington, the burning of the U.S. Capitol and Navy Yard, and the rescue of his family from slavery as well as shipyard working conditions,1835 Washington Navy Yard labor strike, Snow Riot, racial tensions and other issues and events of nineteenth century, military and civilian life.

Roland C. McConnell (1910-2007) was a Canadian-born American archivist, historian and author.

Sarah Johnson was an African American woman who was born into slavery at Mount Vernon, George Washington's estate in Fairfax, Virginia. She worked as a domestic, cleaning and caring for the residence. During the process, she became an informal historian of all of the mansion's furnishings. After the end of the Civil War, she was hired by the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, ultimately becoming a council member of the organization. She bought four acres of Mount Vernon land to establish a small farm. The book Sarah Johnson's Mount Vernon (2008) tells the story of her life within the complex community of people who inhabited Mount Vernon.

The Emancipation Memorial, also known as the Freedman's Memorial or the Emancipation Group was a monument in Park Square in Boston. Designed and sculpted by Thomas Ball and erected in 1879, its sister statue is located in Lincoln Park in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, D.C. The Boston statue was taken down by the City of Boston on December 29, 2020, following a unanimous vote from the Boston Art Commission on June 30 to remove the memorial.

The history of slavery in Colorado began centuries before Colorado achieved statehood when Spanish colonists of Santa Fe de Nuevo México (1598–1848) enslaved Native Americans, called Genízaros. Southern Colorado was part of the Spanish territory until 1848. Comanche and Utes raided villages of other indigenous people and enslaved them.