The Federation of Expellees is a non-profit organization formed in West Germany on 27 October 1957 to represent the interests of German nationals of all ethnicities and foreign ethnic Germans and their families who either fled their homes in parts of Central and Eastern Europe, or were forcibly expelled following World War II.

The Potsdam Agreement was the agreement among three of the Allies of World War II: the United Kingdom, the United States, and the Soviet Union after the war ended in Europe on 1 August 1945 and it was published the next day. A product of the Potsdam Conference, it concerned the military occupation and reconstruction of Germany, its border, and the entire European Theatre of War territory. It also addressed Germany's demilitarisation, reparations, the prosecution of war criminals and the mass expulsion of ethnic Germans from various parts of Europe. France was not invited to the conference but formally remained one of the powers occupying Germany.

During the later stages of World War II and the post-war period, Germans and Volksdeutsche fled and were expelled from various Eastern and Central European countries, including Czechoslovakia, and from the former German provinces of Lower and Upper Silesia, East Prussia, and the eastern parts of Brandenburg (Neumark) and Pomerania (Hinterpommern), which were annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union.

In Nazi German terminology, Volksdeutsche were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of volksdeutsch, with Volksdeutsche denoting a singular female, and Volksdeutscher, a singular male. The words Volk and völkisch conveyed the meanings of "folk".

The right of return is a principle in international law which guarantees everyone's right of voluntary return to, or re-entry to, their country of origin or of citizenship. The right of return is part of the broader human rights concept freedom of movement and is also related to the legal concept of nationality. While many states afford their citizens the right of abode, the right of return is not restricted to citizenship or nationality in the formal sense. It allows stateless persons and for those born outside their country to return for the first time, so long as they have maintained a "genuine and effective link".

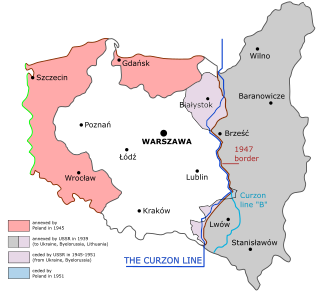

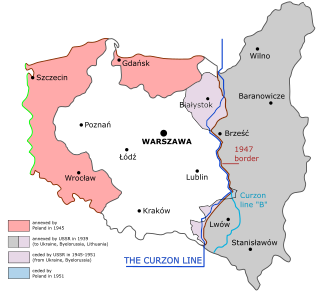

Seventeen days after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, which marked the beginning of the Second World War, the Soviet Union entered the eastern regions of Poland and annexed territories totalling 201,015 square kilometres (77,612 sq mi) with a population of 13,299,000. Inhabitants besides ethnic Poles included Belarusian and Ukrainian major population groups, and also Czechs, Lithuanians, Jews, and other minority groups.

The German Expellees or Heimatvertriebene are 12-16 million German citizens and ethnic Germans who fled or were expelled after World War II from parts of Germany annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union and from other countries, who found refuge in both West and East Germany, and Austria.

The former eastern territories of Germany refer in present-day Germany to those territories east of the current eastern border of Germany, i.e., the Oder–Neisse line, which historically had been considered German and which were annexed by Poland and the Soviet Union after World War II in Europe. In most of these territories, Germans used to be the dominant or sole ethnicity. In contrast to the lands awarded to the restored Polish state by the Treaty of Versailles after World War I, the German territories lost with the Potsdam Agreement after World War II in Europe on 2 August 1945 were either almost exclusively inhabited by Germans before 1945, mixed German-Polish with a German majority, or mixed German-Czech with a German majority (Glatz). Virtually the entire German population of the territories that did not flee voluntarily in the face of the Red Army advance of 1945, was expelled to Germany, with their possessions being expropriated.

The registered German minority in Poland at the Polish census of 2021 were 144,177.

The Federal Law on Refugees and Exiles is a federal law passed by the Federal Republic of Germany on 19 May 1953 to regulate the legal situation of ethnic German refugees and expellees who fled or were expelled after World War II from the former eastern territories of the German Reich and other areas of Central and Eastern Europe. The law was amended on 3 September 1971.

Demographic estimates of the flight and expulsion of Germans have been derived by either the compilation of registered dead and missing persons or by a comparison of pre-war and post-war population data. Estimates of the number of displaced Germans vary in the range of 12.0–16.5 million. The death toll attributable to the flight and expulsions was estimated at 2.2 million by the West German government in 1958 using the population balance method. German records which became public in 1987 have caused some historians in Germany to put the actual total at about 500,000 based on the listing of confirmed deaths. The German Historical Museum puts the figure at 600,000 victims and says that the official figure of 2 million did not stand up to later review. However, the German Red Cross still maintains that the total death toll of the expulsions is 2,251,500 persons.

The presence of German-speaking populations in Central and Eastern Europe is rooted in centuries of history, with the settling in northeastern Europe of Germanic peoples predating even the founding of the Roman Empire. The presence of independent German states in the region, and later the German Empire as well as other multi-ethnic countries with German-speaking minorities, such as Hungary, Poland, Imperial Russia, etc., demonstrates the extent and duration of German-speaking settlements.

The flight and expulsion of Germans from Poland was the largest of a series of flights and expulsions of Germans in Europe during and after World War II. The German population fled or was expelled from all regions which are currently within the territorial boundaries of Poland: including the former eastern territories of Germany annexed by Poland after the war and parts of pre-war Poland; despite acquiring territories from Germany, the Poles themselves were also expelled from the former eastern territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union. West German government figures of those evacuated, migrated, or expelled by 1950 totaled 8,030,000. Research by the West German government put the figure of Germans emigrating from Poland from 1951 to 1982 at 894,000; they are also considered expellees under German Federal Expellee Law.

The expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia after World War II was part of a series of evacuations and deportations of Germans from Central and Eastern Europe during and after World War II.

The Polish population transfers in 1944–1946 from the eastern half of prewar Poland, were the forced migrations of Poles toward the end and in the aftermath of World War II. These were the result of a Soviet Union policy that had been ratified by the main Allies of World War II. Similarly, the Soviet Union had enforced policies between 1939 and 1941 which targeted and expelled ethnic Poles residing in the Soviet zone of occupation following the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland. The second wave of expulsions resulted from the retaking of Poland from the Wehrmacht by the Red Army. The USSR took over territory for its western republics.

The Prussian deportations, also known as the Prussian expulsions of Poles, were the mass expulsions of Poles from German-controlled Prussia between 1885 and 1890. More than 30,000 Poles from the Austrian and Russian Partition of Poland who did not obtain German citizenship when the German Empire was formed in 1871 were deported from the Prussian part of divided Poland to the respective Austrian and Russian Partitions of the no-longer existing Commonwealth.

History of Pomerania (1945–present) covers the history of Pomerania during World War II aftermath, the Communist and since 1989 Democratic era.

The Recovered Territories or Regained Lands, also known as the Western Borderlands, and previously as the Western and Northern Territories, Postulated Territories and Returning Territories, are the former eastern territories of Germany and the Free City of Danzig that became part of Poland after World War II, at which time most of their German inhabitants were forcibly deported.

The Oder–Neisse line is an unofficial term for the modern border between Germany and Poland. The line generally follows the Oder and Lusatian Neisse rivers, meeting the Baltic Sea in the north. A small portion of Polish territory does fall west of the line, including the cities of Szczecin and Świnoujście.

Documents on the Expulsion of the Germans from Eastern-Central Europe is the abridged English translation of a multi-volume publication that was created by a commission of West German historians between 1951 and 1961 to document the population transfer of Germans from East-Central Europe that had occurred after World War II. Created by the Federal Ministry for Displaced Persons, Refugees and War Victims, the commission headed by Theodor Schieder consisted primarily of well-known historians, however with a Nazi past. Therefore, while in the immediate post war period the commission was regarded as composed of very accomplished historians, the later assessment of its members changed. The later historians are debating how reliable are the findings of the commission, and to what degree they were influenced by Nazi and nationalist point of view.