Emotions are mental states brought on by neurophysiological changes, variously associated with thoughts, feelings, behavioral responses, and a degree of pleasure or displeasure. There is no scientific consensus on a definition. Emotions are often intertwined with mood, temperament, personality, disposition, or creativity.

Empathy is the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing from within their frame of reference, that is, the capacity to place oneself in another's position. Definitions of empathy encompass a broad range of social, cognitive, and emotional processes primarily concerned with understanding others. Types of empathy include cognitive empathy, emotional empathy, somatic empathy, and spiritual empathy.

Psychological horror is a subgenre of horror and psychological fiction with a particular focus on mental, emotional, and psychological states to frighten, disturb, or unsettle its audience. The subgenre frequently overlaps with the related subgenre of psychological thriller, and often uses mystery elements and characters with unstable, unreliable, or disturbed psychological states to enhance the suspense, horror, drama, tension, and paranoia of the setting and plot and to provide an overall creepy, unpleasant, unsettling, or distressing atmosphere.

Emotional contagion is a form of social contagion that involves the spontaneous spread of emotions and related behaviors. Such emotional convergence can happen from one person to another, or in a larger group. Emotions can be shared across individuals in many ways, both implicitly or explicitly. For instance, conscious reasoning, analysis, and imagination have all been found to contribute to the phenomenon. The behaviour has been found in humans, other primates, dogs, and chickens.

Affect, in psychology, refers to the underlying experience of feeling, emotion, attachment, or mood.

Emotion is defined as any mental experience with high intensity and high hedonic content. The existence and nature of emotions in non-human animals are believed to be correlated with those of humans and to have evolved from the same mechanisms. Charles Darwin was one of the first scientists to write about the subject, and his observational approach has since developed into a more robust, hypothesis-driven, scientific approach. Cognitive bias tests and learned helplessness models have shown feelings of optimism and pessimism in a wide range of species, including rats, dogs, cats, rhesus macaques, sheep, chicks, starlings, pigs, and honeybees. Jaak Panksepp played a large role in the study of animal emotion, basing his research on the neurological aspect. Mentioning seven core emotional feelings reflected through a variety of neuro-dynamic limbic emotional action systems, including seeking, fear, rage, lust, care, panic and play. Through brain stimulation and pharmacological challenges, such emotional responses can be effectively monitored.

Appraisal theory is the theory in psychology that emotions are extracted from our evaluations of events that cause specific reactions in different people. Essentially, our appraisal of a situation causes an emotional, or affective, response that is going to be based on that appraisal. An example of this is going on a first date. If the date is perceived as positive, one might feel happiness, joy, giddiness, excitement, and/or anticipation, because they have appraised this event as one that could have positive long-term effects, i.e. starting a new relationship, engagement, or even marriage. On the other hand, if the date is perceived negatively, then our emotions, as a result, might include dejection, sadness, emptiness, or fear. Reasoning and understanding of one's emotional reaction becomes important for future appraisals as well. The important aspect of the appraisal theory is that it accounts for individual variability in emotional reactions to the same event.

Mood management theory posits that the consumption of messages, particularly entertaining messages, is capable of altering prevailing mood states, and that the selection of specific messages for consumption often serves the regulation of mood states.

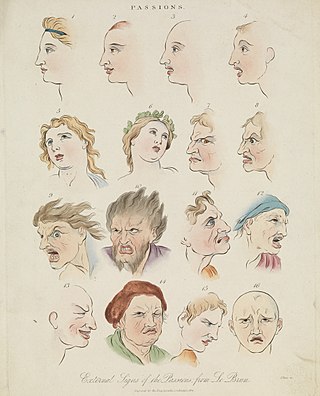

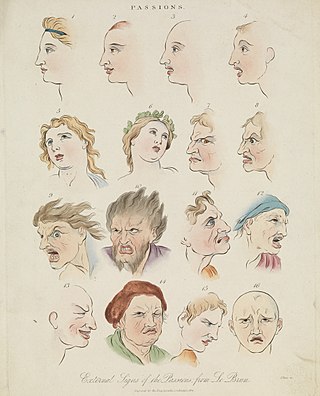

Affect displays are the verbal and non-verbal displays of affect (emotion). These displays can be through facial expressions, gestures and body language, volume and tone of voice, laughing, crying, etc. Affect displays can be altered or faked so one may appear one way, when they feel another. Affect can be conscious or non-conscious and can be discreet or obvious. The display of positive emotions, such as smiling, laughing, etc., is termed "positive affect", while the displays of more negative emotions, such as crying and tense gestures, is respectively termed "negative affect".

Aesthetic emotions are emotions that are felt during aesthetic activity or appreciation. These emotions may be of the everyday variety or may be specific to aesthetic contexts. Examples of the latter include the sublime, the beautiful, and the kitsch. In each of these respects, the emotion usually constitutes only a part of the overall aesthetic experience, but may play a more or less definitive function for that state.

Emotional responsivity is the ability to acknowledge an affective stimuli by exhibiting emotion. It is a sharp change of emotion according to a person's emotional state. Increased emotional responsivity refers to demonstrating more response to a stimulus. Reduced emotional responsivity refers to demonstrating less response to a stimulus. Any response exhibited after exposure to the stimulus, whether it is appropriate or not, would be considered as an emotional response. Although emotional responsivity applies to nonclinical populations, it is more typically associated with individuals with schizophrenia and autism.

Empathic concern refers to other-oriented emotions elicited by, and congruent with the perceived welfare of, someone in need. These other-oriented emotions include feelings of tenderness, sympathy, compassion and soft-heartedness.

Excitation-transfer theory purports that residual excitation from one stimulus will amplify the excitatory response to another stimulus, though the hedonic valences of the stimuli may differ. The excitation-transfer process is not limited to a single emotion. For example, when watching a movie, a viewer may be angered by seeing the hero wronged by the villain, but this initial excitation may intensify the viewer's pleasure in witnessing the villain's punishment later. Thus, although the excitation from the original stimulus of seeing the hero wronged was cognitively accessed as anger, the excitation after the second stimulus of seeing the villain punished is cognitively assessed as pleasure, though part of the excitation from the second stimulus is residual from the first.

However, the excitation-transfer process requires the presence of three conditions. One: the second stimulus occurs before the complete decay of residual excitation from the first stimulus. Two: there is the misattribution of excitation, that is, after exposure to the second stimulus, the individual experiencing the excitation attributes full excitation to the second stimulus. Three: the individual has not reached an excitatory threshold before exposure to the second stimulus.

Affective disposition theory (ADT), in its simplest form, states that media and entertainment users make moral judgments about characters in a narrative which in turn affects their enjoyment of the narrative. This theory was first posited by Zillmann and Cantor (1977), and many offshoots have followed in various areas of entertainment. Entertainment users make constant judgments of a character's actions, and these judgments enable the user to determine which character they believe is the "good guy" or the "villain". However, in an article written in 2004, Raney examined the fundamental ADT assumption that viewers of drama always form their dispositions toward characters through moral judgment of motives and conduct. Raney argued that viewers/consumers of entertainment media could form positive dispositions toward characters before any moral scrutinizing occurs. He proposed that viewers sometimes develop story schemas that provide them "with the cognitive pegs upon which to hang their initial interpretations and expectations of characters". The basic idea of the affective disposition theory is used as a way to explain how emotions become part of the entertainment experience.

In psychology of art, the relationship between art and emotion has newly been the subject of extensive study thanks to the intervention of esteemed art historian Alexander Nemerov. Emotional or aesthetic responses to art have previously been viewed as basic stimulus response, but new theories and research have suggested that these experiences are more complex and able to be studied experimentally. Emotional responses are often regarded as the keystone to experiencing art, and the creation of an emotional experience has been argued as the purpose of artistic expression. Research has shown that the neurological underpinnings of perceiving art differ from those used in standard object recognition. Instead, brain regions involved in the experience of emotion and goal setting show activation when viewing art.

Pain empathy is a specific variety of empathy that involves recognizing and understanding another person's pain.

Empathy quotient (EQ) is a psychological self-report measure of empathy developed by Simon Baron-Cohen and Sally Wheelwright at the Autism Research Centre at the University of Cambridge. EQ is based on a definition of empathy that includes cognition and affect.

Vicarious embarrassment is the feeling of embarrassment from observing the embarrassing actions of another person. Unlike general embarrassment, vicarious embarrassment is not the feelings of embarrassment for yourself or for your own actions, but instead by feeling embarrassment for somebody else after witnessing that other person experiences an embarrassing event. These emotions can be perceived as pro-social, and some say they can be seen as motives for following socially and culturally acceptable behavior.

Dolf Zillmann is dean emeritus, and professor of information sciences, communication and psychology at the University of Alabama (UA). Zillmann predominantly conducted research in media psychology, a branch of psychology focused on the effects of media consumption on human affect, developing and expanding a range of theories within media psychology and communication. His work centred on the relation between aggression, emotion, and arousal through media consumption, predominantly in pornography and violent genres of movie and television. His research also includes the effects of music consumption, video games, and sports.

Alexandra "Alex" Chen is a character from the Life Is Strange video game series published by Square Enix. Created by American developer Deck Nine, she first appears in the 2021 video game Life Is Strange: True Colors as its main protagonist. Alex has the supernatural power to see, experience, and manipulate the emotions of people around her. At the outset of the game, she moves from Portland, Oregon to the fictional Colorado town of Haven Springs to live with her brother Gabe Chen, who dies in an accident soon after her arrival. She is forced to utilize her power of empathy, the volatility of which has made her life difficult up to this point, in order to discover the truth behind her brother's tragic death and find closure for herself.