Zooarchaeology merges the disciplines of zoology and archaeology, focusing on the analysis of animal remains within archaeological sites. This field, managed by specialists known as zooarchaeologists or faunal analysts, examines remnants such as bones, shells, hair, chitin, scales, hides, and proteins, such as DNA, to derive insights into historical human-animal interactions and environmental conditions. While bones and shells tend to be relatively more preserved in archaeological contexts, the survival of faunal remains is generally infrequent. The degradation or fragmentation of faunal remains presents challenges in the accurate analysis and interpretation of data.

How and when horses became domesticated has been disputed. Although horses appeared in Paleolithic cave art as early as 30,000 BC, these were wild horses and were probably hunted for meat. The clearest evidence of early use of the horse as a means of transport is from chariot burials dated c. 2000 BC. However, an increasing amount of evidence began to support the hypothesis that horses were domesticated in the Eurasian Steppes in approximately 3500 BC. Discoveries in the context of the Botai culture had suggested that Botai settlements in the Akmola Province of Kazakhstan are the location of the earliest domestication of the horse. Warmouth et al. (2012) pointed to horses having been domesticated around 3000 BC in what is now Ukraine and Western Kazakhstan.

Archaeogenetics is the study of ancient DNA using various molecular genetic methods and DNA resources. This form of genetic analysis can be applied to human, animal, and plant specimens. Ancient DNA can be extracted from various fossilized specimens including bones, eggshells, and artificially preserved tissues in human and animal specimens. In plants, ancient DNA can be extracted from seeds and tissue. Archaeogenetics provides us with genetic evidence of ancient population group migrations, domestication events, and plant and animal evolution. The ancient DNA cross referenced with the DNA of relative modern genetic populations allows researchers to run comparison studies that provide a more complete analysis when ancient DNA is compromised.

The Seven Daughters of Eve is a 2001 semi-fictional book by Bryan Sykes that presents the science of human origin in Africa and their dispersion to a general audience. Sykes explains the principles of genetics and human evolution, the particularities of mitochondrial DNA, and analyses of ancient DNA to genetically link modern humans to prehistoric ancestors.

Bioarchaeology in Europe describes the study of biological remains from archaeological sites. In the United States it is the scientific study of human remains from archaeological sites.

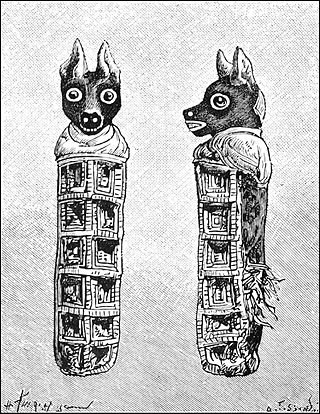

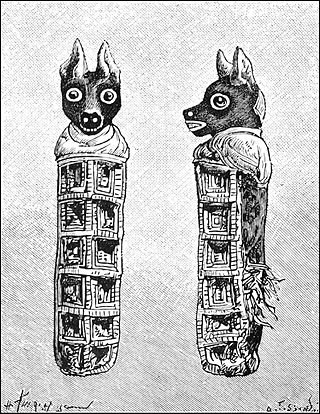

Paleopathology, also spelled palaeopathology, is the study of ancient diseases and injuries in organisms through the examination of fossils, mummified tissue, skeletal remains, and analysis of coprolites. Specific sources in the study of ancient human diseases may include early documents, illustrations from early books, painting and sculpture from the past. All these objects provide information on the evolution of diseases as well as how past civilizations treated conditions. Studies have historically focused on humans, although there is no evidence that humans are more prone to pathologies than any other animal.

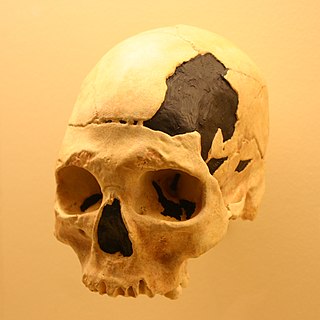

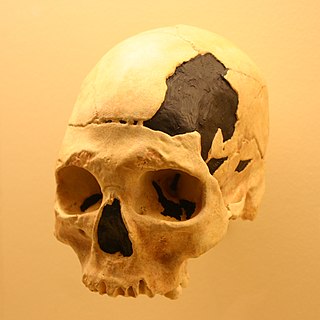

Ancient DNA (aDNA) is DNA isolated from ancient specimens. Due to degradation processes ancient DNA is more degraded in comparison with contemporary genetic material. Even under the best preservation conditions, there is an upper boundary of 0.4–1.5 million years for a sample to contain sufficient DNA for sequencing technologies. The oldest sample ever sequenced is estimated to be 1.65 million years old. Genetic material has been recovered from paleo/archaeological and historical skeletal material, mummified tissues, archival collections of non-frozen medical specimens, preserved plant remains, ice and from permafrost cores, marine and lake sediments and excavation dirt. In 2022, two-million year old genetic material was found in Greenland, and is currently considered the oldest DNA discovered so far.

Jane Ellen Buikstra is an American anthropologist and bioarchaeologist. Her 1977 article on the biological dimensions of archaeology coined and defined the field of bioarchaeology in the US as the application of biological anthropological methods to the study of archaeological problems. Throughout her career, she has authored over 20 books and 150 articles. Buikstra's current research focuses on an analysis of the Phaleron cemetery near Athens, Greece.

Peștera cu Oase is a system of 12 karstic galleries and chambers located near the city Anina, in the Caraș-Severin county, southwestern Romania, where some of the oldest European early modern human (EEMH) remains, between 42,000 and 37,000 years old, have been found.

Haplogroup N1a is a human mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup.

The Denisovans or Denisova hominins(di-NEE-sə-və) are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic, and lived, based on current evidence, from 285 to 25 thousand years ago. Denisovans are known from few physical remains; consequently, most of what is known about them comes from DNA evidence. No formal species name has been established pending more complete fossil material.

Denisova Cave is a cave in the Bashelaksky Range of the Altai mountains, Siberian Federal District, Russia. The cave has provided items of great paleoarchaeological and paleontological interest. Bone fragments of the Denisova hominin originate from the cave, including artifacts dated to around 40,000 BP. Remains of a 32,000-year-old prehistoric species of horse have also been found in the cave.

On Your Knees Cave (49-PET-408) is an archaeological site located in southeastern Alaska. Human remains were found at the site in 1996 that dated between 9,730 ±60 and 9,880±50 radiocarbon YBP or a calendrical date of 10,300 YBP. In addition to human skeletal remains, stone tools and animal bones were discovered. DNA analyses performed on the human skeletal remains document the presence of mitochondrial haplogroup D which occurs widely in the Americas. Isotopic analysis indicated that the individual had a primarily marine based diet.

Ata is the common name given to the 6-inch (15 cm) long skeletal remains of a human fetus found in 2003 in the Chilean ghost town of La Noria, in the Atacama Desert. DNA analysis done in 2018 on the premature human fetus identified unusual mutations associated with dwarfism and scoliosis, though these findings were later disputed. The remains were found by Oscar Muñoz, who later sold them; the current owner is Ramón Navia-Osorio, a Spanish businessman.

Anzick-1 is a Paleo-Indian male infant whose remains were found in south central Montana, United States, in 1968, and date to 13,000–12,850 years BP. The child was found with more than 115 tools made of stone and antlers and dusted with red ocher, suggesting an honorary burial. Anzick-1 is the only human who has been discovered from the Clovis Complex, and is the first ancient Native American genome to be fully sequenced.

Medieval Bioarchaeology is the study of human remains recovered from medieval archaeological sites. Bioarchaeology aims to understand populations through the analysis of human skeletal remains and this application of bioarchaeology specifically aims to understand medieval populations. There is an interest in the Medieval Period when it comes to bioarchaeology, because of how differently people lived back then as opposed to now, in regards to not only their everyday life, but during times of war and famine as well. The biology and behavior of those that lived in the Medieval Period can be analyzed by understanding their health and lifestyle choices.

As with all modern European nations, a large degree of 'biological continuity' exists between Bosnians and Bosniaks and their ancient predecessors with Y chromosomal lineages testifying to predominantly Paleolithic European ancestry. Studies based on bi-allelic markers of the NRY have shown the three main ethnic groups of Bosnia and Herzegovina to share, in spite of some quantitative differences, a large fraction of the same ancient gene pool distinct for the region. Analysis of autosomal STRs have moreover revealed no significant difference between the population of Bosnia and Herzegovina and neighbouring populations.

Michelle Alexander is a bioarchaeologist with an interest in multi-faith societies and is Senior Lecturer in Bioarchaeology at the University of York.

Hubert Walter was a German anthropologist and human biologist.

Near Eastern bioarchaeology covers the study of human skeletal remains from archaeological sites in Cyprus, Egypt, Levantine coast, Jordan, Turkey, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Yemen.