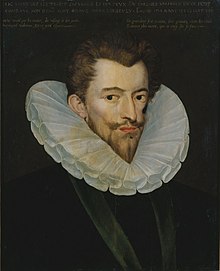

Charles de Lorraine, duc de Mayenne was a French noble, governor, military commander and rebel during the latter French Wars of Religion. Born in 1554, the second son of François de Lorraine, duke of Guise and Anne d'Este, Mayenne inherited his fathers' position of Grand Chambellan in 1563 upon his death. He fought at the siege of Poitiers for the crown in 1569, and crusaded against the Ottomans in 1572. He served under the command of the king's brother Anjou during the siege of La Rochelle in the fourth war of religion, during which he was wounded. While the siege progressed, his uncle was killed by a cannonball, and he inherited his position as governor of Bourgogne. That same year, his marquisate of Mayenne was elevated to a duché pairie. He travelled with Anjou when he was elected as king of the Commonwealth and was a member of his court there until early 1574 when he departed on crusade again. Returning to France, he served in the fifth war of religion for Anjou, now king Henri III of France, but his badly underfunded army was unable to seriously impede the Protestant mercenary force under Casimir. He aligned himself with the Catholic Ligue that rose up in opposition to the generous Peace of Monsieur and fought in the sixth war of religion that resulted, serving at the sieges of La Charité-sur-Loire and Issoire. During 1576, he married Henriette de Savoie-Villars, securing a sizable inheritance in the south west, and the title of Admiral on the death of her father in 1578. Mayenne was granted full command of a royal army during the seventh war of religion in 1580, besieging the Protestant stronghold of La Mure successfully, and clearing several holdout towns after the peace. In 1582 he was obliged to surrender his title of Admiral to Joyeuse, a favourite of Henri. The following year he was involved in an abortive plan to invade England, though it came to nothing due to lack of funds.

Charles-Emmanuel de Savoie, prince de Genevois and duc de Nemours was a French prince étranger, governor, military commander and rebel during the latter French Wars of Religion. The eldest son of Jacques de Savoie and Anne d'Este, Nemours was a member of a prominent princely family. He entered French political at the age of 18 as a partisan of the second Catholic ligue, rallying cavalry to the rebel army, and assisting in forcing Henri III to capitulate to their demands. In the following years, the king was compelled by the terms of the peace to make war against Protestantism. The former rebel ligueurs hoped the 'cowed' king would afford them advantage, but Henri was keen to dilute the authority of the former rebels. As a result Nemours' position as colonel-general of the light cavalry was diluted with several appointments of royal favourites. During this period, Nemours coveted the governate of the Lyonnais, which had previously been held by his father before 1571. When François de Mandelot, who held the office, died in November 1588, Henri was compelled to recognise Nemours as the new governor due to his political weakness. Frustrated at his continued capitulations to the ligue, on 23 December 1588, Henri assassinated the leader of the ligue the duke of Guise. In the wake of the assassination, Nemours and other ligueur leaders were arrested by the king. Nemours was however quickly able to bribe his guards and secure freedom.

Charles de Lorraine, duc d'Aumale was a French noble, military commander and governor during the latter French Wars of Religion. The son of Claude, Duke of Aumale and Louise de Brézé, Aumale inherited his families position in north eastern France, and his fathers title of Grand Veneur. Educated as a fervent Catholic, his clients engineered the creation of the first national Catholic Ligue in 1576, and he continued to support the remnants of the organisation after the Treaty of Bergerac caused much of the ligue to dissolve. During the sixth civil war that the ligue had induced, he fought with the king's brother Alençon at the sieges of La Charité-sur-Loire and Issoire. During the seventh civil war in 1579, he brought his ligueur forces to support the royal army under Marshal Matignon during the siege of La Fère but left on bitter terms with the commander when the siege was brought to a close on generous terms.

Louis II de Lorraine, cardinal de Guise was a French prelate, Cardinal and politician during the latter French Wars of Religion. The third son of François de Lorraine, duke of Guise and Anne d'Este Louis was destined for a career in the church. His uncle Cardinal Lorraine resigned his offices of Archbishop of Reims to him in 1574, and the death of his other uncle Louis I de Lorraine, Cardinal de Guise passed his ecclesiastical empire on to him upon his death in 1578. At which time the king made him Cardinal. Cardinal Guise actively involved himself in the first Catholic Ligue that rose up in opposition to the generous Peace of Monsieur which brought the fifth war of religion to a close in 1576. The ligue succeeded in resuming the civil war the next year and a harsher peace was concluded. Over the following years of peace, he would feud with Épernon, and receive Henri III's new honour when he was made a chevalier de l'Ordre du Saint-Esprit in 1578 among the first cohort. Finally reaching the ecclesiastical age at which he could assume his responsibilities as Archbishop of Reims in 1583 he entered the city in triumph and oversaw a council at which he pushed for the promulgation of the Tridentine Decrees.

Louis de Gonzague, Duke of Nevers was a soldier, governor and statesman during the French Wars of Religion. His father and brother were reigning dukes of Mantua. He came to France in 1549, and fought for Henri II of France during the latter Italian Wars, getting himself captured during the battle of Saint Quentin. Due to his Italian connections he was seen as a useful figure to have as governor of French Piedmont, a post he would hold until Henri III ceded the territory in 1574. In 1565 his patron, Catherine de' Medici secured for him a marriage with the key heiress Henriette de Clèves, elevating him to duke of Nevers and count of Rethel. He fought for the crown through the early wars of religion, receiving a bad injury in the third war. At this time he formed a close bond with the young Anjou, future king Henri III, a bond that would last until the king's death.

Charles de Bourbon, Cardinal de Bourbon, Archbishop of Rouen was a French noble, prelate and disputed King of France as the Catholic Ligue candidate from 2 August 1589 – 9 May 1590. Born the third son of Charles of Bourbon, Duke of Vendôme and Françoise d'Alençon he was destined for a career in the church. As a member of the House of Bourbon-Vendôme he was one of the premier Prince du sang. Already having secured several sees, he was made a Cardinal by Pope Paul III in January 1548. In 1550 he received the office of Archbishop of Rouen making him the Primate of Normandy. The following year the promotion of Bourbon to Patriarch of the French church was threatened by King Henry II to secure concessions from the Pope. During the Italian Wars which resumed that year, Bourbon played a role by supporting Catherine de Medici's regency governments in France and briefly holding a lieutenant-generalship in Picardy. In 1557 the Pope appointed the Cardinals Bourbon, Lorraine and Châtillon as the leaders of an inquisition in France to root out heresy. The effectiveness of their inquisition would be obstructed by both the king and the Parlements and by July 1558 their appointments were voided by the Parlement of Paris.

Henri de Bourbon, prince dauphin d'Auvergne, then prince de Dombes and duc de Montpensier was a French prince du sang, duke, military commander, governor and royal councillor during the final days of the French Wars of Religion. The son of François de Bourbon, Duke of Montpensier and Renée d'Anjou, Montpensier remained loyal to king Henri III after he entered war with the Catholic ligue (league) in December 1588. As a reward for his loyalty he was made first governor of Basse (lower) Auvergne, and then, upon the capture of the comte de Soissons he was established as governor of Bretagne.

Charles I de Lorraine, duc d'Elbeuf was a French noble, military commander and governor during the French Wars of Religion. The son of the most minor cadet house of the children of Claude, Duke of Guise, Elbeuf initially lacked the prominence of his cousins, however his succession to the Rieux inheritance made him important. Over the following decades he would gradually consolidate more of it under his authority, until by his death in 1605, all of the county of Harcourt belonged to the Elbeufs. A young man in 1573, he travelled with the king's brother to assume his kingship of the Commonwealth. Upon the prince's return as Henri III of France in 1574 Elbeuf would receive the honour of assuming the position of grand chamberlain during the coronation. After the establishment of the Ordre du Saint-Esprit in 1579, Elbeuf would be elevated as a knight of this chivalric body. The following year he supported the king's brother Alençon in his negotiations with the Dutch States General to assume the role of king. In the wake of these successful, if fraught, negotiations, he was nominated by Alençon as lieutenant-general of his army. Elbeuf and Alençon would travel to the Spanish Netherlands where they would relieve the besieged town of Cambrai, to much acclaim from the citizenry. Shortly after this, relations soured between Elbeuf and the prince, and Elbeuf retired back to his estates with the excuse of an illness, being refused when he offered to return the following year. In September 1581, his marquisate of Elbeuf was elevated to a peerage duchy, greatly elevating Elbeuf's social standing.

François de Bourbon, duc de Montpensier and prince dauphin d'Auvergne was a French noble, goveror, diplomat and military commander during the French Wars of Religion. The son of Louis de Bourbon, duke of Montpensier and Jacqueline de Longwy, Montpensier got his start in politics as he was made the successor to his father's control of the governorship of Dauphiné, taking over the post in 1567. He participated alongside his father in the siege of La Rochelle during the fourth civil war and with the defection of the Catholic Damville to the rebel cause during the fifth civil war, Montpensier was established as a parallel governor to Damville's charge over the territory of Languedoc, though Damville would never be formally dispossed. During this war he further held responsibility for one of the four royal armies, leading it into the Rhône valley. By 1582 Montpensier's father was nearing death, and he was chosen to replace his father as leader of a diplomatic mission to England to secure a marriage between the king's brother and Elizabeth I, however this would not be a success. Failing in his efforts to marry Elizabeth, Alençon turned his attentions to Nederland, accepting an invitation to become their king. Montpensier would lead one of the armies that reinforced him in the kingdom, though the prince would sabotage his position in the territory the following year.

Charles de Cossé, 1st Duke of Brissac was a French noble, military commander, governor, courtier and rebel during the latter French Wars of Religion. Son of the Charles I de Cossé and Charlotte d'Esquetot, Brissac was born into a family with a strong military reputation, both his father and uncle being French Marshals. As a second son Brissac was not initially intended to assume the titles of his father, but his brother Timoléon de Cossé was killed during a siege in 1569. Brissac was intimately involved in the French response to the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580, being selected by Catherine de Medici the queen's mother as one of the two military commanders for the expedition. In June 1582 he departed with a fleet under the overall authority of Strozzi, another Marshals' son. They were met with disaster at the Battle of Vila Franca do Campo, Strozzi was killed and Brissac took responsibility for extracting the ships that could be saved from the superior enemy. Catherine desired for him to lead another expedition but Henri overruled her, and Brissac looked to the duke of Guise for purpose, becoming involved in the abortive plans for an invasion of England. After these too fell through, Brissac involved himself in the revived Catholic ligue which rose in response to the death of the king's brother in June 1584 and the subsequent threat of a Protestant king. As a result of the dauphins death, Brissac received command of the Château d'Angers. The ligue resolved to make war on the king to get him to revise his policy, and Brissac campaigned in Normandie but was bested by Épernon at the siege of Gien. The war was brought to a close with a favourable settlement to the ligue in September.

On 23 December 1588, Henri I, Duke of Guise was assassinated by the Quarante Cinq serving King Henri III. The event was one of the most critical moments of the French Wars of Religion. The duke had achieved, since 1584, considerable power over the kingdom of France, through his alliance with the Ligue movement, which he had co-opted for the cause of resisting the king's chosen successor of Navarre, a Protestant. Despite some effort to resist Guise and the ligue, Henri III had been forced by his weak position to accede to their continued demands. After the Day of the Barricades in May 1588, the ligue expelled Henri from Paris, and Henri was forced to make Guise lieutenant general of the kingdom, call an Estates General and sign an Edict of Union in July which prohibited Navarre from succeeding to the throne and outlawed Protestantism in France. Increasingly unable to bear the humiliations Guise and the ligue forced upon him, he was further outraged by the Estates General. The body, largely ligueur dominated, rejected his attempt to chastise Guise for forming associations, diverted tax income to Guise's cousin Mayenne and rejected all compromise with the king.

Claude de Lorraine, chevalier d'Aumale was a French churchman, noble and military commander during the French Wars of Religion. The second son of Claude, Duke of Aumale and Louise de Brézé, Aumale was destined for a life in the church. His uncles Cardinal Lorraine and Cardinal Guise ensured that he was granted many abbeys, that brought him a sizable income. At the age of 19 in 1583, he travelled to Malta to perform his service as a Knight of the Order of Saint John, finding success in his campaign.

Joachim de Dinteville ( –1607) was a French noble, lieutenant-general and favourite of Henri III and Henri IV. Born into a prominent Champenois family of the noblesse seconde, Dinteville became close with Anjou, brother to Charles IX. In 1572 he was elevated to the position of Premier Gentilhomme de la Chambre by the duke, a key role in his household. He travelled with Anjou for the conduct of the siege of La Rochelle in 1573, and fought with him there. Upon Anjou's election as king of the Commonwealth, he travelled east with his lord, and served in his household for his brief tenure as king there. On Anjou's return to take the crown of France, Dinteville departed from his household, assuming responsibilities in Champagne, where he led the Second Estate of Troyes in opposing the attempt of Guise to affiliate the city with the national Catholic ligue. As Henri's brother Alençon moved closer to his plans of assuming the kingship of the rebellious Spanish Netherlands, Dinteville assisted the king in attempting to draw him, and thus France away from a potential confrontation with Spain. He assisted Henri's mother Catherine de Medici in her negotiations with Henri's cousin Navarre in 1579. In December of that year, Henri appointed Dinteville to replace the aged sieur de Barbizieulx as lieutenant-general of Champagne, making him second only to the governor Guise. Henri recognised Dinteville's valuable connections across the noblesse seconde of the province.

Louis d'Angennes, seigneur de Maintenon was a French noble, diplomat, governor and soldier during the French Wars of Religion. The son of Jacques d'Angennes and Isabelle Cottereau, he first achieved prominence in 1568, when he was established as governor of Le Mans. He reinvigorated the cities Catholic ligue for a fight against Protestantism. At that time he became grand maréchal de logis de la maison du roi, a post he would hold until 1579. He fought for the crown during the brief seventh civil war at the Siege of La Fère. In 1580 he was established as one of the king's Chambellan. The following year he would be elevated to the most senior order of French chivalry, being among the 1581 intake as a Ordre du Saint-Esprit. He and his brother Rambouillet participated in the Assembly of Notables that sought to consider a financial reform package from 1583-1584. His selection to participate in the Estates General of 1588 was forced through by the king over the objection of the governor of Chartres who had hoped to select a less royalist delegate. At the Estates, when word arrived that the duke of Savoie had invaded French held Saluzzo he whipped the Second Estate into a patriotic fervour with a speech advocating first the recapture of Saluzzo, and then the declaration of war against Spain. However the ligueur members of the other States got the nobility back into line, and his plan went nowhere.

Gaspard de Schomberg, comte de Nanteuil was a French soldier, courtier, diplomat, statesman and governor during the French Wars of Religion. Of Sachsen descent, Gaspard naturalised as French. He began his career during the first French War of Religion, when he fought with the Protestants against the crown, raising mercenaries in the Holy Roman Empire for the prince of Condé. The crown was impressed with his abilities, and co-opted his services, during the third civil war he would fight against the Protestants. In 1570 he was made a gentilhomme de la chambre du roi, and then a Chambellan and in these years he would conduct a series of diplomatic missions to further French foreign policy with the princes of the empire. In 1573 he helped prepare the way for Anjou, travel to his new kingdom, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. When Anjou returned to France as Henri III Schomberg supported him in the civil war he inherited, reporting on the mercenary situation in the empire, and fighting at the Battle of Dormans. His wealth during this period allowed him to take advantage of the Duke of Guise's financial woes, securing for himself the county of Nanteuil-le-Haudoin in 1578 for several hundred thousand livres.

François de Balsac, seigneur d’Entragues was a French noble, governor, military commander and courtier during the French Wars of Religion. Born into a prominent noble family from the Massif-Central, Entragues began his career serving as an officer in the company of the duke of Longueville. He caught the attention of the court, and was made lieutenant-general of the duchy of Orléans in 1568. This was shortly followed with specific authorities over the important city of Orléans in 1571. Unlike his two brothers Clermont and Dunes he was not a favourite of Henri III. He thus aligned with the duke of Guise and the Catholic ligue in the succession crisis that began in 1584 upon the death of the king's brother Alençon. When the ligue went to war with the king in 1585 in opposition to his chosen heir, his Protestant cousin Navarre, Entragues entered rebellion with them. Bringing the city of Orléans with him, he was at first driven back by royalist forces under the duke of Montpensier, holding off the duke with cannonades from the citadel, before returning to the offensive with an effort against Gien. This effort too was pushed aside by the royal favourite the duke of Épernon, however the war still concluded with a capitulation to the ligue.

François du Plessis, sieur de Richelieu was a French noble, military officer, and royal official during the French Wars of Religion. Born into an obscure noble family from Poitou, Richelieu began his career in the service of the Montpensier. He fought in the third war of religion under the command of the son of the duke of Montpensier at Jarnac and Moncontour. He again fought under the Montpensier, this time prince de Dombes during the fifth war of religion. It was on the recommendation of the Montpensier that Richelieu was elevated to the post of Grand Prévôt de l'Hôtel in February 1578, which the king combined with the new office of Grand Prévôt de France, giving him police authority both over the king's household and France at large. He would take to this role with enthusiasm, becoming a consistent advocate of the royal will. By the 1580s he had become a major creditor of the monarchy, serving as the intermediary between Italian banking families and the crown, this eventually brought him into financial ruin.

Antoine de Brichanteau, Marquis de Beauvais-Nangis was a French noble, military commander, and royal favourite during the French Wars of Religion and early-17th century. Born into a noble Briard family, Beauvais-Nangis began his military career at a young age, serving during the third French War of Religion at Jarnac and Moncontour, among other engagements. At the former, his valour was recognised by the brother of the king, Anjou, who took him into his household. He fought at the famous Siege of La Rochelle in 1573 and joined Anjou in the Commonwealth when he was elected as king. Upon Anjou's return to France as King Henri III, Beauvais-Nangis was elevated as commander of the Picard regiments during the fifth War of Religion. In November of that year, he was granted the prestigious role of Maître de camp of the French Guard. In the sixth civil war, he fought at the siege of Hiers-Brouage. In 1579, he was dispatched on a diplomatic mission to Portugal. By his return, however, his relations were becoming increasingly frayed with the king. He had repeatedly found himself in dispute with other favourites of the king, and resented his lack of financial compensation for the diplomatic mission. In 1581, he embarrassed the king in a confrontation he undertook with Henri's brother Alençon, in which he killed several of the duke's men. Henri felt obliged to disgrace him, and in March of that year, he was relieved of the post of Maître de camp. He spent the next several years aggrieved on his estates in Brie.

The Estates General of 1593 was a national meeting of the three orders of France that met from January to August 1593. Unlike any other Estates General of France, it was convoked without the authority of a king, at the behest of duke of Mayenne, lieutenant-general of the kingdom for the rebel Catholic ligue (league) movement, which controlled Paris and many other cities. The Catholic ligue had reformed in 1584 to oppose the succession to the throne of the Protestant king of Navarre. They proposed the candidacy of Cardinal Bourbon, Navarre's Catholic uncle. In 1589, the king died, and while royalists recognised Navarre as Henri IV, ligueur (leaguer) controlled areas instead recognised Bourbon as Charles X. In 1590, Bourbon died, leaving the ligue without a king. Many ligueur nobles were happy without a king, but pressure was brought to bear on Mayenne, and by late 1592 he agreed to convoke an Estates General to elect a new one. This Estates would not be recognised by Henri.

The Estates General of 1576 was a national meeting of the three orders of France; the clergy, nobility and common people. It was called as one of the many concessions made by the crown to the Protestant/moderate Catholic rebels to bring the Fifth War of Religion to a close. The generous terms of the peace made with the rebels provoked a strong backlash from militant Catholics who established the first Catholic Ligue (League) in opposition to the terms. Henri at first sought to suppress the ligue before attempting to co-opt it. Both king Henri III and the ligue looked to the upcoming Estates General to secure advantage. For the first time in the history of the Estates General, a fierce election campaign would follow between Protestant, royalist and ligueur candidates, in the end very few Protestants would be represented in the Estates.

![The new gardes des sceaux Francois II de Montholon [fr] Francois II de montholon 1505383.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ce/Fran%C3%A7ois_II_de_montholon_1505383.jpg/220px-Fran%C3%A7ois_II_de_montholon_1505383.jpg)