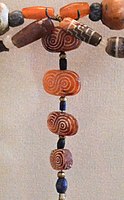

Carnelian is a brownish-red mineral commonly used as a semiprecious stone. Similar to carnelian is sard, which is generally harder and darker; the difference is not rigidly defined, and the two names are often used interchangeably. Both carnelian and sard are varieties of the silica mineral chalcedony colored by impurities of iron oxide. The color can vary greatly, ranging from pale orange to an intense almost-black coloration. Significant localities include Yanacodo (Peru); Ratnapura ; and Thailand. It has been found in Indonesia, Brazil, India, Russia (Siberia), and Germany. In the United States, the official State Gem of Maryland is also a variety of carnelian called Patuxent River stone.

Sumer is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia, emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. Like nearby Elam, it is one of the cradles of civilization, along with Egypt, the Indus Valley, the Erligang culture of the Yellow River valley, Caral-Supe, and Mesoamerica. Living along the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Sumerian farmers grew an abundance of grain and other crops, a surplus which enabled them to form urban settlements. The world's earliest known texts come from the Sumerian cities of Uruk and Jemdet Nasr, and date to between c. 3350 – c. 2500 BC, following a period of proto-writing c. 4000 – c. 2500 BC.

Susa was an ancient city in the lower Zagros Mountains about 250 km (160 mi) east of the Tigris, between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers in modern day Iran. One of the most important cities of the Ancient Near East, Susa served as the capital of Elam and the winter capital of Achaemenid Empire, and remained a strategic centre during the Parthian and Sasanian periods.

Elam was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretching from the lowlands of what is now Khuzestan and Ilam Province as well as a small part of southern Iraq. The modern name Elam stems from the Sumerian transliteration elam(a), along with the later Akkadian elamtu, and the Elamite haltamti. Elamite states were among the leading political forces of the Ancient Near East. In classical literature, Elam was also known as Susiana, a name derived from its capital Susa.

Dilmun, or Telmun, was an ancient East Semitic-speaking civilization in Eastern Arabia mentioned from the 3rd millennium BC onwards. Based on contextual evidence, it was located in the Persian Gulf, on a trade route between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley civilisation, close to the sea and to artesian springs. Dilmun encompassed Bahrain, Kuwait, and eastern Saudi Arabia. This area is certainly what is meant by references to "Dilmun" among the lands conquered by King Sargon II and his descendants.

Mesannepada, Mesh-Ane-pada or Mes-Anne-pada was the first king listed for the First Dynasty of Ur on the Sumerian king list. He is listed to have ruled for 80 years, having overthrown Lugal-kitun of Uruk: "Then Unug (Uruk) was defeated and the kingship was taken to Urim (Ur)". In one of his seals, found in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, he is also described as king of Kish.

Meluḫḫa or Melukhkha is the Sumerian name of a prominent trading partner of Sumer during the Middle Bronze Age. Its identification remains an open question, but most scholars associate it with the Indus Valley civilisation.

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider to have been a nascent empire.

The First Dynasty of Ur was a 26th-25th century BCE dynasty of rulers of the city of Ur in ancient Sumer. It is part of the Early Dynastic period III of the history of Mesopotamia. It was preceded by the earlier First Dynasty of Kish and the First Dynasty of Uruk.

Shulgi of Ur was the second king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. He reigned for 48 years, from c. 2094 – c. 2046 BC or possibly c. 2030 – 1982 BC. His accomplishments include the completion of construction of the Great Ziggurat of Ur, begun by his father Ur-Nammu. On his inscriptions, he took the titles "King of Ur", "King of Sumer and Akkad" and "King of the four corners of the universe". He used the symbol for divinity before his name, marking his apotheosis, from the 23rd year of his reign.

The Master of Animals, Lord of Animals, or Mistress of the Animals is a motif in ancient art showing a human between and grasping two confronted animals. The motif is very widespread in the art of the Ancient Near East and Egypt. The figure may be female or male, it may be a column or a symbol, the animals may be realistic or fantastical, and the human figure may have animal elements such as horns, an animal upper body, an animal lower body, legs, or cloven feet. Although what the motif represented to the cultures that created the works probably varies greatly, unless shown with specific divine attributes, when male the figure is typically described as a hero by interpreters.

The Early Dynastic period is an archaeological culture in Mesopotamia that is generally dated to c. 2900 – c. 2350 BC and was preceded by the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. It saw the development of writing and the formation of the first cities and states. The ED itself was characterized by the existence of multiple city-states: small states with a relatively simple structure that developed and solidified over time. This development ultimately led to the unification of much of Mesopotamia under the rule of Sargon, the first monarch of the Akkadian Empire. Despite this political fragmentation, the ED city-states shared a relatively homogeneous material culture. Sumerian cities such as Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Umma, and Nippur located in Lower Mesopotamia were very powerful and influential. To the north and west stretched states centered on cities such as Kish, Mari, Nagar, and Ebla.

Marhaši was a 3rd millennium BC polity situated east of Elam, on the Iranian plateau, in Makran. It is known from Mesopotamian sources, but its precise location has not been identified, though some scholars link it with the Jiroft culture. Henri-Paul Francfort and Xavier Tremblay proposed identifying the kingdom of Marhashi with Ancient Margiana on the basis of the Akkadian textual and archaeological evidence.

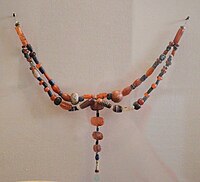

Imports to Ur reflect the cultural and trade connections of the Sumerian city of Ur. During the period of the Early Dynastic III royal cemetery, Ur was importing elite goods from geographically distant places. These objects include precious metals such as gold and silver, and semi-precious stones, namely lapis lazuli and carnelian. These objects are all the more impressive considering the distance from which they traveled to reach Mesopotamia and Ur specifically.

The art of Mesopotamia has survived in the record from early hunter-gatherer societies on to the Bronze Age cultures of the Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian empires. These empires were later replaced in the Iron Age by the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian empires. Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Mesopotamia brought significant cultural developments, including the oldest examples of writing.

The Royal Cemetery at Ur is an archaeological site in modern-day Dhi Qar Governorate in southern Iraq. The initial excavations at Ur took place between 1922 and 1934 under the direction of Leonard Woolley in association with the British Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States.

Indus–Mesopotamia relations are thought to have developed during the second half of 3rd millennium BCE, until they came to a halt with the extinction of the Indus valley civilization after around 1900 BCE. Mesopotamia had already been an intermediary in the trade of lapis lazuli between the Indian subcontinent and Egypt since at least about 3200 BCE, in the context of Egypt-Mesopotamia relations.

The Sukkalmah Dynasty, also Epartid Dynasty after the founder Eparti/Ebarat, was an early dynasty of West Asia in the ancient region of Elam, to the southeast of Babylonia. It corresponds to the latest part of the Old Elamite period.

Egypt–Mesopotamia relations were the relations between the civilisations of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, in the Middle East. They seem to have developed from the 4th millennium BCE, starting in the Uruk period for Mesopotamia and the half a millennium younger Gerzean culture of Prehistoric Egypt, and constituted a largely one way body of influences from Mesopotamia into Egypt.

The Sumerian economy refers to the systems of trade in ancient Mesopotamia. Sumerian city-states relied on trade due to a lack of certain materials, which had to be brought in from other regions. Their trade networks extended to places such as Oman, Arabia, Anatolia, the Indus River Valley, and the Iranian Plateau. Sumerians also bought and sold property, but land tied to the temples could not be traded. There were three types of land—Nigenna, Kurra, and Urulal—and only Urulal land could be traded; Nigenna land belonged to the temple, while Kurra land belonged to the people working in the temple. Within Sumer, the Sumerians could use silver, barley, or cattle as currency