Related Research Articles

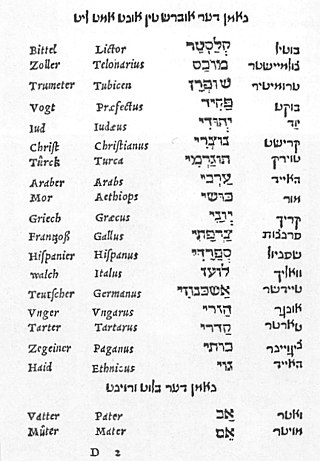

Antisemitism is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. This sentiment is a form of racism, and a person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Primarily, antisemitic tendencies may be motivated by negative sentiment towards Jews as a people or by negative sentiment towards Jews with regard to Judaism. In the former case, usually presented as racial antisemitism, a person's hostility is driven by the belief that Jews constitute a distinct race with inherent traits or characteristics that are repulsive or inferior to the preferred traits or characteristics within that person's society. In the latter case, known as religious antisemitism, a person's hostility is driven by their religion's perception of Jews and Judaism, typically encompassing doctrines of supersession that expect or demand Jews to turn away from Judaism and submit to the religion presenting itself as Judaism's successor faith—this is a common theme within the other Abrahamic religions. The development of racial and religious antisemitism has historically been encouraged by the concept of anti-Judaism, which is distinct from antisemitism itself.

Ad hominem, short for argumentum ad hominem, refers to several types of arguments which are fallacious. Typically this term refers to a rhetorical strategy where the speaker attacks the character, motive, or some other attribute of the person making an argument rather than attacking the substance of the argument itself. This avoids genuine debate by creating a personal attack as a diversion often using a totally irrelevant, but often highly charged attribute of the opponent's character or background. The most common form of this fallacy is "A" makes a claim of "fact," to which "B" asserts that "A" has a personal trait, quality or physical attribute that is repugnant thereby going entirely off-topic, and hence "B" concludes that "A" has their "fact" wrong - without ever addressing the point of the debate. Many contemporary politicians routinely use ad hominem attacks, which can be encapsulated to a derogatory nickname for a political opponent.

Fallacies of definition are the various ways in which definitions can fail to explain terms. The phrase is used to suggest an analogy with an informal fallacy. Definitions may fail to have merit, because they: are overly broad, use obscure or ambiguous language, or contain circular reasoning; those are called fallacies of definition. Three major fallacies are: overly broad, overly narrow, and mutually exclusive definitions, a fourth is: incomprehensible definitions, and one of the most common is circular definitions.

A false etymology is a false theory about the origin or derivation of a specific word or phrase. When a false etymology becomes a popular belief in a cultural/linguistic community, it is a folk etymology. Nevertheless, folk/popular etymology may also refer to the process by which a word or phrase is changed because of a popular false etymology. To disambiguate the usage of the term "folk/popular etymology", Ghil'ad Zuckermann proposes a clear-cut distinction between the derivational-only popular etymology (DOPE) and the generative popular etymology (GPE): the DOPE refers to a popular false etymology involving no neologization, and the GPE refers to neologization generated by a popular false etymology.

In logic, equivocation is an informal fallacy resulting from the use of a particular word/expression in multiple senses within an argument.

The Aryan race is an obsolete historical race concept that emerged in the late-19th century to describe people who descend from the Proto-Indo-Europeans as a racial grouping. The terminology derives from the historical usage of Aryan, used by modern Indo-Iranians as an epithet of "noble". Anthropological, historical, and archaeological evidence does not support the validity of this concept.

In classical rhetoric and logic, begging the question or assuming the conclusion is an informal fallacy that occurs when an argument's premises assume the truth of the conclusion. Historically, begging the question refers to a fault in a dialectical argument in which the speaker assumes some premise that has not been demonstrated to be true. In modern usage, it has come to refer to an argument in which the premises assume the conclusion without supporting it. This makes it more or less synonymous with circular reasoning.

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. Its definition is contested, in part due to conflicting theoretical understandings of social and kinship structures, and also reflecting the problematic application of this concept to extremely diverse human societies. The concept is often contrasted by anthropologists with other social and kinship groups, being hierarchically larger than a lineage or clan, but smaller than a chiefdom, ethnicity, nation or state. These terms are similarly disputed. In some cases tribes have legal recognition and some degree of political autonomy from national or federal government, but this legalistic usage of the term may conflict with anthropological definitions.

Linguistics is the scientific study of language, involving analysis of language form, language meaning, and language in context.

Semitic people or Semites is an obsolete term for an ethnic, cultural or racial group associated with people of the Middle East, including Arabs, Jews, Akkadians, and Phoenicians. The terminology is now largely unused outside the grouping "Semitic languages" in linguistics. First used in the 1770s by members of the Göttingen school of history, this biblical terminology for race was derived from Shem, one of the three sons of Noah in the Book of Genesis, together with the parallel terms Hamites and Japhetites.

In modern Hebrew and Yiddish goy is a term for a gentile, a non-Jew. Through Yiddish, the word has been adopted into English also to mean "gentile", sometimes in a pejorative sense. As a word principally used by Jews to describe non-Jews, it is a term for the ethnic out-group.

The phrase pathetic fallacy is a literary term for the attribution of human emotion and conduct to things found in nature that are not human. It is a kind of personification that occurs in poetic descriptions, when, for example, clouds seem sullen, when leaves dance, or when rocks seem indifferent. The English cultural critic John Ruskin coined the term in the third volume of his work Modern Painters (1856).

A root is the core of a word that is irreducible into more meaningful elements. In morphology, a root is a morphologically simple unit which can be left bare or to which a prefix or a suffix can attach. The root word is the primary lexical unit of a word, and of a word family, which carries aspects of semantic content and cannot be reduced into smaller constituents. Content words in nearly all languages contain, and may consist only of, root morphemes. However, sometimes the term "root" is also used to describe the word without its inflectional endings, but with its lexical endings in place. For example, chatters has the inflectional root or lemma chatter, but the lexical root chat. Inflectional roots are often called stems. A root, or a root morpheme, in the stricter sense, may be thought of as a monomorphemic stem.

The Caucasian race is an obsolete racial classification of humans based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. The Caucasian race was historically regarded as a biological taxon which, depending on which of the historical race classifications was being used, usually included ancient and modern populations from all or parts of Europe, Western Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, North Africa, and the Horn of Africa.

Folk etymology – also known as (generative) popular etymology, analogical reformation, (morphological)reanalysis and etymological reinterpretation – is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more familiar one through popular usage. The form or the meaning of an archaic, foreign, or otherwise unfamiliar word is reinterpreted as resembling more familiar words or morphemes.

Informal fallacies are a type of incorrect argument in natural language. The source of the error is not just due to the form of the argument, as is the case for formal fallacies, but can also be due to their content and context. Fallacies, despite being incorrect, usually appear to be correct and thereby can seduce people into accepting and using them. These misleading appearances are often connected to various aspects of natural language, such as ambiguous or vague expressions, or the assumption of implicit premises instead of making them explicit.

The indigenous population of the Maghreb region of North Africa encompass a diverse grouping of several heterogenous ethnic groups who predate the arrival of Arabs in the Arab migration to the Maghreb. They are collectively known as Berbers or Amazigh in English. The native plural form Imazighen is sometimes also used in English. While "Berber" is more widely known among English-speakers, its usage is a subject of debate, due to its historical background as an exonym and present equivalence with the Arabic word for "barbarian." When speaking English, indigenous North Africans typically refer to themselves as "Amazigh."

The plant name Cannabis is derived originally from a Scythian or Thracian word, which loaned into Persian as kanab, then into Greek as κάνναβις and subsequently into Latin as cannabis. The Germanic word that gives rise to English hemp may be an early Germanic loan from the same source.

References

- 1 2 3 Sihler, Andrew (2000). Language History. Amsterdam studies in the theory and history of linguistic science. Series IV, Current issues in linguistic theory. Vol. 191. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 131–133. ISBN 90-272-3698-4.

- ↑ Wilson, Kenneth G. (1993). "Etymological Fallacy". The Columbia Guide to Standard American English.

- ↑ Templeton, A. (2016). EVOLUTION AND NOTIONS OF HUMAN RACE. In Losos J. & Lenski R. (Eds.), How Evolution Shapes Our Lives: Essays on Biology and Society (pp. 346–361). Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv7h0s6j.26.

- ↑ Wagner, Jennifer K.; Yu, Joon-Ho; Ifekwunigwe, Jayne O.; Harrell, Tanya M.; Bamshad, Michael J.; Royal, Charmaine D. (February 2017). "Anthropologists' views on race, ancestry, and genetics". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 162 (2): 318–327. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23120. PMC 5299519. PMID 27874171.

- ↑ Lipstadt, Deborah (2019). Antisemitism: Here and Now. Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0-80524337-6.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia Britannica: Semitic people can't be called antisemitic". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 2022-02-04. Retrieved 2023-11-15.

- ↑ "Origins and concept of anti-Semitism | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-11-29.