A centripetal force is a force that makes a body follow a curved path. The direction of the centripetal force is always orthogonal to the motion of the body and towards the fixed point of the instantaneous center of curvature of the path. Isaac Newton described it as "a force by which bodies are drawn or impelled, or in any way tend, towards a point as to a centre". In Newtonian mechanics, gravity provides the centripetal force causing astronomical orbits.

In physics, the Coriolis force is an inertial force that acts on objects in motion within a frame of reference that rotates with respect to an inertial frame. In a reference frame with clockwise rotation, the force acts to the left of the motion of the object. In one with anticlockwise rotation, the force acts to the right. Deflection of an object due to the Coriolis force is called the Coriolis effect. Though recognized previously by others, the mathematical expression for the Coriolis force appeared in an 1835 paper by French scientist Gaspard-Gustave de Coriolis, in connection with the theory of water wheels. Early in the 20th century, the term Coriolis force began to be used in connection with meteorology.

In classical physics and special relativity, an inertial frame of reference is a frame of reference in which the laws of nature take on a particularly simple form.

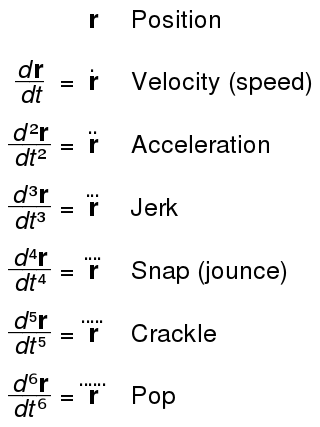

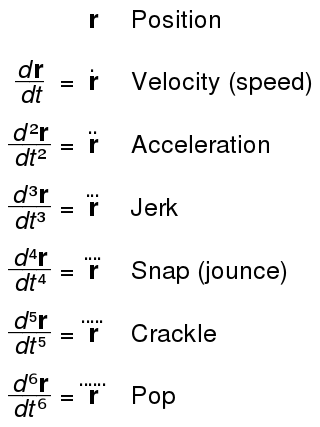

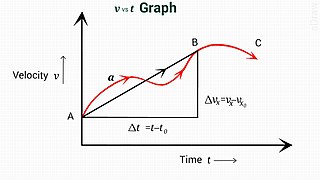

In physics, jerk (also known as jolt) is the rate of change of an object's acceleration over time. It is a vector quantity (having both magnitude and direction). Jerk is most commonly denoted by the symbol j and expressed in m/s3 (SI units) or standard gravities per second (g0/s).

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In other words, if the axis of rotation of a body is itself rotating about a second axis, that body is said to be precessing about the second axis. A motion in which the second Euler angle changes is called nutation. In physics, there are two types of precession: torque-free and torque-induced.

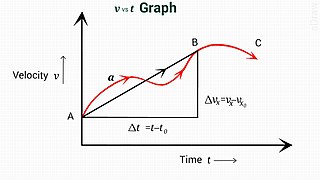

In physics, equations of motion are equations that describe the behavior of a physical system in terms of its motion as a function of time. More specifically, the equations of motion describe the behavior of a physical system as a set of mathematical functions in terms of dynamic variables. These variables are usually spatial coordinates and time, but may include momentum components. The most general choice are generalized coordinates which can be any convenient variables characteristic of the physical system. The functions are defined in a Euclidean space in classical mechanics, but are replaced by curved spaces in relativity. If the dynamics of a system is known, the equations are the solutions for the differential equations describing the motion of the dynamics.

In physics, angular velocity, also known as angular frequency vector, is a pseudovector representation of how the angular position or orientation of an object changes with time, i.e. how quickly an object rotates around an axis of rotation and how fast the axis itself changes direction.

In physics, a rigid body, also known as a rigid object, is a solid body in which deformation is zero or negligible. The distance between any two given points on a rigid body remains constant in time regardless of external forces or moments exerted on it. A rigid body is usually considered as a continuous distribution of mass.

In the physical science of dynamics, rigid-body dynamics studies the movement of systems of interconnected bodies under the action of external forces. The assumption that the bodies are rigid simplifies analysis, by reducing the parameters that describe the configuration of the system to the translation and rotation of reference frames attached to each body. This excludes bodies that display fluid, highly elastic, and plastic behavior.

In classical mechanics, Euler's rotation equations are a vectorial quasilinear first-order ordinary differential equation describing the rotation of a rigid body, using a rotating reference frame with angular velocity ω whose axes are fixed to the body. Their general vector form is

A fictitious force is a force that appears to act on a mass whose motion is described using a non-inertial frame of reference, such as a linearly accelerating or rotating reference frame. Fictitious forces are invoked to maintain the validity and thus use of Newton's second law of motion, in frames of reference which are not inertial.

A rotating frame of reference is a special case of a non-inertial reference frame that is rotating relative to an inertial reference frame. An everyday example of a rotating reference frame is the surface of the Earth.

In theoretical physics a Coriolis field is one of the apparent gravitational fields felt by a rotating or forcibly-accelerated body, together with the centrifugal field and the Euler field.

Rotation around a fixed axis or axial rotation is a special case of rotational motion around an axis of rotation fixed, stationary, or static in three-dimensional space. This type of motion excludes the possibility of the instantaneous axis of rotation changing its orientation and cannot describe such phenomena as wobbling or precession. According to Euler's rotation theorem, simultaneous rotation along a number of stationary axes at the same time is impossible; if two rotations are forced at the same time, a new axis of rotation will result.

In classical mechanics, Appell's equation of motion is an alternative general formulation of classical mechanics described by Josiah Willard Gibbs in 1879 and Paul Émile Appell in 1900.

Centrifugal force is an inertial force in Newtonian mechanics that appears to act on all objects when viewed in a rotating frame of reference. It is directed radially away from the axis of rotation. The magnitude of centrifugal force F on an object of mass m at the distance r from the axis of rotation of a frame of reference rotating with angular velocity ω is:

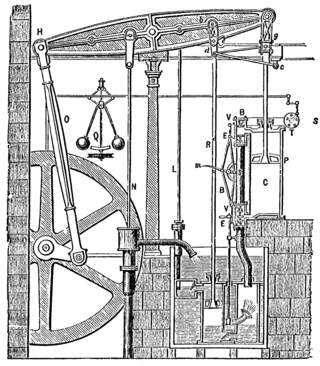

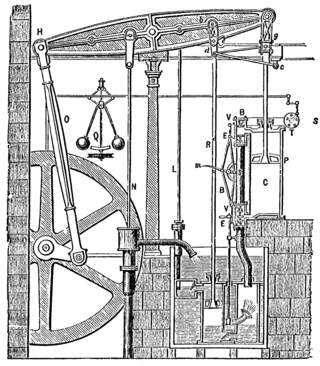

Classical mechanics is a physical theory describing the motion of objects such as projectiles, parts of machinery, spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. The development of classical mechanics involved substantial change in the methods and philosophy of physics. The qualifier classical distinguishes this type of mechanics from physics developed after the revolutions in physics of the early 20th century, all of which revealed limitations in classical mechanics.

Mechanics of planar particle motion is the analysis of the motion of particles gravitationally attracted to one another observed from non-inertial reference frames and the generalization of this problem to planetary motion. This type of analysis is closely related to centrifugal force, two-body problem, orbit and Kepler's laws of planetary motion. The mechanics of planar particle motion fall in the general field of analytical dynamics, and helps determine orbits from the given force laws. This article is focused more on the kinematic issues surrounding planar motion, which are the determination of the forces necessary to result in a certain trajectory given the particle trajectory.

Isaac Newton's rotating spheres argument attempts to demonstrate that true rotational motion can be defined by observing the tension in the string joining two identical spheres. The basis of the argument is that all observers make two observations: the tension in the string joining the bodies and the rate of rotation of the spheres. Only for the truly non-rotating observer will the tension in the string be explained using only the observed rate of rotation. For all other observers a "correction" is required that accounts for the tension calculated being different from the one expected using the observed rate of rotation. It is one of five arguments from the "properties, causes, and effects" of true motion and rest that support his contention that, in general, true motion and rest cannot be defined as special instances of motion or rest relative to other bodies, but instead can be defined only by reference to absolute space. Alternatively, these experiments provide an operational definition of what is meant by "absolute rotation", and do not pretend to address the question of "rotation relative to what?" General relativity dispenses with absolute space and with physics whose cause is external to the system, with the concept of geodesics of spacetime.