Related Research Articles

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not due to any immediate external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that are associated with specific symptoms and signs. A disease may be caused by external factors such as pathogens or by internal dysfunctions. For example, internal dysfunctions of the immune system can produce a variety of different diseases, including various forms of immunodeficiency, hypersensitivity, allergies and autoimmune disorders.

Eugenics is a set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population, historically by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or promoting those judged to be superior.

Transhumanism is a philosophical movement that advocates for the transformation of the human condition by developing and making widely available sophisticated technologies able to greatly modify or enhance human intellect and physiology.

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher was a British eugenicist, statistician, geneticist, and professor. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who almost single-handedly created the foundations for modern statistical science" and "the single most important figure in 20th century statistics". In genetics, his work used mathematics to combine Mendelian genetics and natural selection; this contributed to the revival of Darwinism in the early 20th-century revision of the theory of evolution known as the modern synthesis. For his contributions to biology, Fisher has been called "the greatest of Darwin’s successors".

Hermann Joseph Muller was an American geneticist, educator, and Nobel laureate best known for his work on the physiological and genetic effects of radiation (mutagenesis), as well as his outspoken political beliefs. Muller frequently warned of long-term dangers of radioactive fallout from nuclear war and nuclear testing, which resulted in greater public scrutiny of these practices.

Genetic testing, also known as DNA testing, is used to identify changes in DNA sequence or chromosome structure. Genetic testing can also include measuring the results of genetic changes, such as RNA analysis as an output of gene expression, or through biochemical analysis to measure specific protein output. In a medical setting, genetic testing can be used to diagnose or rule out suspected genetic disorders, predict risks for specific conditions, or gain information that can be used to customize medical treatments based on an individual's genetic makeup. Genetic testing can also be used to determine biological relatives, such as a child's parentage through DNA paternity testing, or be used to broadly predict an individual's ancestry. Genetic testing of plants and animals can be used for similar reasons as in humans, to gain information used for selective breeding, or for efforts to boost genetic diversity in endangered populations.

Joshua Lederberg, ForMemRS was an American molecular biologist known for his work in microbial genetics, artificial intelligence, and the United States space program. He was 33 years old when he won the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering that bacteria can mate and exchange genes. He shared the prize with Edward Tatum and George Beadle, who won for their work with genetics.

Pathophysiology – a convergence of pathology with physiology – is the study of the disordered physiological processes that cause, result from, or are otherwise associated with a disease or injury. Pathology is the medical discipline that describes conditions typically observed during a disease state, whereas physiology is the biological discipline that describes processes or mechanisms operating within an organism. Pathology describes the abnormal or undesired condition, whereas pathophysiology seeks to explain the functional changes that are occurring within an individual due to a disease or pathologic state.

Lionel Sharples Penrose, FRS was an English psychiatrist, medical geneticist, paediatrician, mathematician and chess theorist, who carried out pioneering work on the genetics of intellectual disability. Penrose was the Galton professor of eugenics (1945-1965), then professor of human genetics (1963–1965) at University College London, and later emeritus professor.

The Society for Biodemography and Social Biology, formerly known as the Society for the Study of Social Biology and before then as the American Eugenics Society, is dedicated to "furthering the discussion, advancement, and dissemination of knowledge about biological and sociocultural forces which affect the structure and composition of human populations."

Dysgenics is the study of factors producing the accumulation and perpetuation of defective or disadvantageous genes and traits in offspring of a particular population or species.

Medical genetics is the branch of medicine that involves the diagnosis and management of hereditary disorders. Medical genetics differs from human genetics in that human genetics is a field of scientific research that may or may not apply to medicine, while medical genetics refers to the application of genetics to medical care. For example, research on the causes and inheritance of genetic disorders would be considered within both human genetics and medical genetics, while the diagnosis, management, and counselling people with genetic disorders would be considered part of medical genetics.

Biotechnology is the application of scientific and engineering principles to the processing of materials by biological agents to provide goods and services. From its inception, biotechnology has maintained a close relationship with society. Although now most often associated with the development of drugs, historically biotechnology has been principally associated with food, addressing such issues as malnutrition and famine. The history of biotechnology begins with zymotechnology, which commenced with a focus on brewing techniques for beer. By World War I, however, zymotechnology would expand to tackle larger industrial issues, and the potential of industrial fermentation gave rise to biotechnology. However, both the single-cell protein and gasohol projects failed to progress due to varying issues including public resistance, a changing economic scene, and shifts in political power.

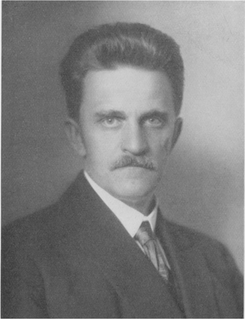

Yuri Filipchenko was a Russian entomologist who coined the terms microevolution and macroevolution, as well as the mentor of geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky. Though he himself was an orthogenetic, he was one of the first scientists to incorporate the laws of Mendel into evolutionary theory and thus had a great influence on The Modern Synthesis. He established a genetics laboratory in Leningrad undertaking experimental work with Drosophila melanogaster. Theodosius Dobzhansky worked with him from 1924. Filipchenko is also known for his work in Soviet eugenics, though his work in the subject would later result in his public denunciation due to the rise of Stalinism and increased criticisms that eugenics represented bourgeois science.

Esther Miriam Zimmer Lederberg was an American microbiologist and a pioneer of bacterial genetics. Notable contributions include the discovery of the bacterial virus λ, the transfer of genes between bacteria by specialized transduction, the development of replica plating, and the discovery of the bacterial fertility factor F.

The Avery–MacLeod–McCarty experiment was an experimental demonstration, reported in 1944 by Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty, that DNA is the substance that causes bacterial transformation, in an era when it had been widely believed that it was proteins that served the function of carrying genetic information. It was the culmination of research in the 1930s and early 20th century at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research to purify and characterize the "transforming principle" responsible for the transformation phenomenon first described in Griffith's experiment of 1928: killed Streptococcus pneumoniae of the virulent strain type III-S, when injected along with living but non-virulent type II-R pneumococci, resulted in a deadly infection of type III-S pneumococci. In their paper "Studies on the Chemical Nature of the Substance Inducing Transformation of Pneumococcal Types: Induction of Transformation by a Desoxyribonucleic Acid Fraction Isolated from Pneumococcus Type III", published in the February 1944 issue of the Journal of Experimental Medicine, Avery and his colleagues suggest that DNA, rather than protein as widely believed at the time, may be the hereditary material of bacteria, and could be analogous to genes and/or viruses in higher organisms.

The State Institute for Racial Biology was a Swedish governmental research institute founded in 1922 with the stated purpose of studying eugenics and human genetics. It was the most prominent institution for the study of "racial science" in Sweden. It was located in Uppsala. In 1958, it was renamed to the State Institute for Human Genetics and is today incorporated as a department of Uppsala University.

"Sickle Cell Anemia, a Molecular Disease" is a 1949 scientific paper by Linus Pauling, Harvey A. Itano, Seymour J. Singer and Ibert C. Wells that established sickle-cell anemia as a genetic disease in which affected individuals have a different form of the metalloprotein hemoglobin in their blood. The paper, published in the November 25, 1949 issue of Science, reports a difference in electrophoretic mobility between hemoglobin from healthy individuals and those with sickle-cell anemia, with those with sickle cell trait having a mixture of the two types. The paper suggests that the difference in electrophoretic mobility is probably due to a different number of ionizable amino acid residues in the protein portion of hemoglobin, and that this change in molecular structure is responsible for the sickling process. It also reports the genetic basis for the disease, consistent with the simultaneous genealogical study by James V. Neel: those with sickle-cell anemia are homozygous for the disease gene, while heterozygous individuals exhibit the usually asymptomatic condition of sickle cell trait.

Aspects of genetics including mutation, hybridisation, cloning, genetic engineering, and eugenics have appeared in fiction since the 19th century.

References

| Look up euphenics in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- ↑ Bud, Robert. The Uses of Life: A History of Biotechnology, Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 167

- ↑ Khanna, Pragya. Essentials of Genetics, I. K. International Pvt Ltd, 2010, p. 367

- ↑ Lederberg, Joshua. "Molecular Biology, Eugenics and Euphenics", Nature 63(198), p. 428

- ↑ Minkoff, Eli and Baker, Pamela. Biology Today: An Issues Approach, Taylor & Francis, 2000, p. 115

- ↑ Pai, Anna. Foundations of Genetics: A Science for Society, McGraw-Hill, 1974, p. 408

- ↑ Burdyuzha, Vladimir. The Future of the Universe and the Future of our Civilization, World Scientific, 2000, pp. 261−263

- ↑ Guttman, Burton. Genetics: The Code of Life, The Rosen Publishing Group, 2011, p. 101

- ↑ Maxson, Linda and Daugherty, Charles. Genetics: A Human Perspective, W.C.Brown, 1992, p. 391

| This genetics article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |