Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psycho-social intervention that aims to reduce symptoms of various mental health conditions, primarily depression and anxiety disorders. Cognitive behavioral therapy is one of the most effective means of treatment for substance abuse and co-occurring mental health disorders. CBT focuses on challenging and changing cognitive distortions and their associated behaviors to improve emotional regulation and develop personal coping strategies that target solving current problems. Though it was originally designed to treat depression, its uses have been expanded to include many issues and the treatment of many mental health conditions, including anxiety, substance use disorders, marital problems, ADHD, and eating disorders. CBT includes a number of cognitive or behavioral psychotherapies that treat defined psychopathologies using evidence-based techniques and strategies.

Drug rehabilitation is the process of medical or psychotherapeutic treatment for dependency on psychoactive substances such as alcohol, prescription drugs, and street drugs such as cannabis, cocaine, heroin or amphetamines. The general intent is to enable the patient to confront substance dependence, if present, and stop substance misuse to avoid the psychological, legal, financial, social, and physical consequences that can be caused.

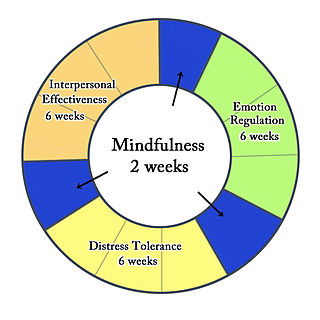

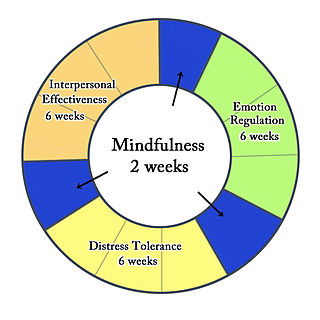

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based psychotherapy that began with efforts to treat personality disorders and interpersonal conflicts. Evidence suggests that DBT can be useful in treating mood disorders and suicidal ideation as well as for changing behavioral patterns such as self-harm and substance use. DBT evolved into a process in which the therapist and client work with acceptance and change-oriented strategies and ultimately balance and synthesize them—comparable to the philosophical dialectical process of thesis and antithesis, followed by synthesis.

In internal medicine, relapse or recidivism is a recurrence of a past condition. For example, multiple sclerosis and malaria often exhibit peaks of activity and sometimes very long periods of dormancy, followed by relapse or recrudescence.

Substance dependence, also known as drug dependence, is a biopsychological situation whereby an individual's functionality is dependent on the necessitated re-consumption of a psychoactive substance because of an adaptive state that has developed within the individual from psychoactive substance consumption that results in the experience of withdrawal and that necessitates the re-consumption of the drug. A drug addiction, a distinct concept from substance dependence, is defined as compulsive, out-of-control drug use, despite negative consequences. An addictive drug is a drug which is both rewarding and reinforcing. ΔFosB, a gene transcription factor, is now known to be a critical component and common factor in the development of virtually all forms of behavioral and drug addictions, but not dependence.

Motivational therapy is a combination of humanistic treatment and enhanced cognitive-behavioral strategies, designed to treat substance use disorders. It is similar to motivational interviewing and motivational enhancement therapy.

Attentional bias refers to how a person's perception is affected by selective factors in their attention. Attentional biases may explain an individual's failure to consider alternative possibilities when occupied with an existing train of thought. For example, cigarette smokers have been shown to possess an attentional bias for smoking-related cues around them, due to their brain's altered reward sensitivity. Attentional bias has also been associated with clinically relevant symptoms such as anxiety and depression.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is an approach to psychotherapy that uses cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) methods in conjunction with mindfulness meditative practices and similar psychological strategies. The origins to its conception and creation can be traced back to the traditional approaches from East Asian formative and functional medicine, philosophy and spirituality, birthed from the basic underlying tenets from classical Taoist, Buddhist and Traditional Chinese medical texts, doctrine and teachings.

Cue reactivity is a type of learned response which is observed in individuals with an addiction and involves significant physiological and psychological reactions to presentations of drug-related stimuli. The central tenet of cue reactivity is that cues previously predicting receipt of drug reward under certain conditions can evoke stimulus associated responses such as urges to use drugs. In other words, learned cues can signal drug reward, in that cues previously associated with drug use can elicit cue-reactivity such as arousal, anticipation, and changes in behavioral motivation. Responses to a drug cue can be physiological, behavioral, or symbolic expressive. The clinical utility of cue reactivity is based on the conceptualization that drug cues elicit craving which is a critical factor in the maintenance and relapse to drug use. Additionally, cue reactivity allows for the development of testable hypotheses grounded in established theories of human behavior. Therefore, researchers have leveraged the cue reactivity paradigm to study addiction, antecedents of relapse, craving, translate pre-clinical findings to clinical samples, and contribute to the development of new treatment methods. Testing cue reactivity in human samples involves exposing individuals with a substance use disorder to drug-related cues and drug neutral cues, and then measuring their reactions by assessing changes in self-reported drug craving and physiological responses.

An addictive behavior is a behavior, or a stimulus related to a behavior, that is both rewarding and reinforcing, and is associated with the development of an addiction. There are two main forms of addiction: substance use disorders and behavioral addiction. The parallels and distinctions between behavioral addictions and other compulsive behavior disorders like bulimia nervosa and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) are still being researched by behavioral scientists.

Polysubstance dependence refers to a type of substance use disorder in which an individual uses at least three different classes of substances indiscriminately and does not have a favorite substance that qualifies for dependence on its own. Although any combination of three substances can be used, studies have shown that alcohol is commonly used with another substance. This is supported by one study on polysubstance use that separated participants who used multiple substances into groups based on their preferred substance. The results of a longitudinal study on substance use led the researchers to observe that excessively using or relying on one substance increased the probability of excessively using or relying on another substance.

Addiction is a neuropsychological disorder characterized by a persistent and intense urge to use a drug or engage in a behaviour that produces natural reward, despite substantial harm and other negative consequences. Repetitive drug use often alters brain function in ways that perpetuate craving, and weakens self-control. This phenomenon – drugs reshaping brain function – has led to an understanding of addiction as a brain disorder with a complex variety of psychosocial as well as neurobiological factors that are implicated in addiction's development. Classic signs of addiction include compulsive engagement in rewarding stimuli, preoccupation with substances or behavior, and continued use despite negative consequences. Habits and patterns associated with addiction are typically characterized by immediate gratification, coupled with delayed deleterious effects.

PTSD or post-traumatic stress disorder, is a psychiatric disorder characterised by intrusive thoughts and memories, dreams or flashbacks of the event; avoidance of people, places and activities that remind the individual of the event; ongoing negative beliefs about oneself or the world, mood changes and persistent feelings of anger, guilt or fear; alterations in arousal such as increased irritability, angry outbursts, being hypervigilant, or having difficulty with concentration and sleep.

About 1 in 7 Americans suffer from active addiction to a particular substance. Addiction can cause physical, psychological, and emotional harm to those who are affected by it. The American Society of Addiction Medicine defines addiction as "a treatable, chronic medical disease involving complex interactions among brain circuits, genetics, the environment, and an individual's life experiences. People with addiction use substances or engage in behaviors that become compulsive and often continue despite harmful consequences." In the world of psychology and medicine, there are two models that are commonly used in understanding the psychology behind addiction itself. One model is referred to as the disease model of addiction. The disease model suggests that addiction is a diagnosable disease similar to cancer or diabetes. This model attributes addiction to a chemical imbalance in an individual's brain that could be caused by genetics or environmental factors. The second model is the choice model of addiction, which holds that addiction is a result of voluntary actions rather than some dysfunction of the brain. Through this model, addiction is viewed as a choice and is studied through components of the brain such as reward, stress, and memory. Substance addictions relate to drugs, alcohol, and smoking. Process addictions relate to non-substance-related behaviors such as gambling, spending money, sexual activity, gaming, spending time on the internet, and eating.

Cognitive emotional behavioral therapy (CEBT) is an extended version of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) aimed at helping individuals to evaluate the basis of their emotional distress and thus reduce the need for associated dysfunctional coping behaviors. This psychotherapeutic intervention draws on a range of models and techniques including dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), mindfulness meditation, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and experiential exercises.

Relapse prevention (RP) is a cognitive-behavioral approach to relapse with the goal of identifying and preventing high-risk situations such as unhealthy substance use, obsessive-compulsive behavior, sexual offending, obesity, and depression. It is an important component in the treatment process for alcohol use disorder, or alcohol dependence. This model founding is attributed to Terence Gorski's 1986 book Staying Sober.

Guided self-change (GSC) treatment has been accepted by American Psychological Association Division 12, Society of Clinical Psychology, as an empirically supported treatment.

Personality theories of addiction are psychological models that associate personality traits or modes of thinking with an individual's proclivity for developing an addiction. Models of addiction risk that have been proposed in psychology literature include an affect dysregulation model of positive and negative psychological affects, the reinforcement sensitivity theory model of impulsiveness and behavioral inhibition, and an impulsivity model of reward sensitization and impulsiveness.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can affect about 3.6% of the U.S. population each year, and 6.8% of the U.S. population over a lifetime. 8.4% of people in the U.S. are diagnosed with substance use disorders (SUD). Of those with a diagnosis of PTSD, a co-occurring, or comorbid diagnosis of a SUD is present in 20–35% of that clinical population.

Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) is an evidence-based mind-body therapy program developed by Eric Garland. It is a therapeutic approach grounded in affective neuroscience that combines mindfulness training with reappraisal and savoring skills. Garland developed this approach by combining the key features of mindfulness training, "Third Wave" cognitive-behavioral therapy, and principles from positive psychology.