Related Research Articles

Antipsychotics, also known as neuroleptics, are a class of psychotropic medication primarily used to manage psychosis, principally in schizophrenia but also in a range of other psychotic disorders. They are also the mainstay together with mood stabilizers in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

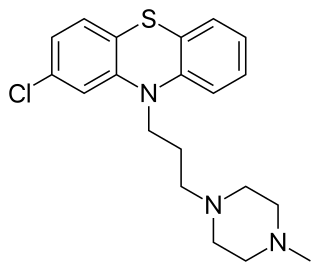

Trifluoperazine, marketed under the brand name Stelazine among others, is a typical antipsychotic primarily used to treat schizophrenia. It may also be used short term in those with generalized anxiety disorder but is less preferred to benzodiazepines. It is of the phenothiazine chemical class.

Haloperidol, sold under the brand name Haldol among others, is a typical antipsychotic medication. Haloperidol is used in the treatment of schizophrenia, tics in Tourette syndrome, mania in bipolar disorder, delirium, agitation, acute psychosis, and hallucinations from alcohol withdrawal. It may be used by mouth or injection into a muscle or a vein. Haloperidol typically works within 30 to 60 minutes. A long-acting formulation may be used as an injection every four weeks by people with schizophrenia or related illnesses, who either forget or refuse to take the medication by mouth.

Typical antipsychotics are a class of antipsychotic drugs first developed in the 1950s and used to treat psychosis. Typical antipsychotics may also be used for the treatment of acute mania, agitation, and other conditions. The first typical antipsychotics to come into medical use were the phenothiazines, namely chlorpromazine which was discovered serendipitously. Another prominent grouping of antipsychotics are the butyrophenones, an example of which is haloperidol. The newer, second-generation antipsychotics, also known as atypical antipsychotics, have largely supplanted the use of typical antipsychotics as first-line agents due to the higher risk of movement disorders in the latter.

The atypical antipsychotics (AAP), also known as second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and serotonin–dopamine antagonists (SDAs), are a group of antipsychotic drugs largely introduced after the 1970s and used to treat psychiatric conditions. Some atypical antipsychotics have received regulatory approval for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, irritability in autism, and as an adjunct in major depressive disorder.

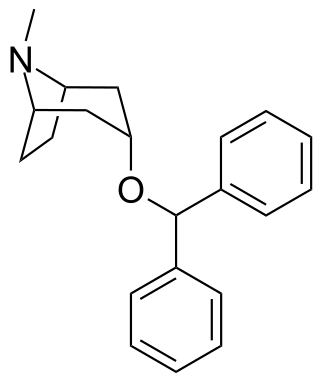

Benzatropine (INN), known as benztropine in the United States and Japan, is a medication used to treat movement disorders like parkinsonism and dystonia, as well as extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotics, including akathisia. It is not useful for tardive dyskinesia. It is taken by mouth or by injection into a vein or muscle. Benefits are seen within two hours and last for up to ten hours.

Akathisia is a movement disorder characterized by a subjective feeling of inner restlessness accompanied by mental distress and an inability to sit still. Usually, the legs are most prominently affected. Those affected may fidget, rock back and forth, or pace, while some may just have an uneasy feeling in their body. The most severe cases may result in aggression, violence, and/or suicidal thoughts. Akathisia is also associated with threatening behaviour and physical aggression that is greatest in patients with mild akathisia, and diminishing with increasing severity of akathisia.

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a disorder that results in involuntary repetitive body movements, which may include grimacing, sticking out the tongue or smacking the lips. Additionally, there may be rapid jerking movements or slow writhing movements. In about 20% of people with TD, the disorder interferes with daily functioning.

Dyskinesia refers to a category of movement disorders that are characterized by involuntary muscle movements, including movements similar to tics or chorea and diminished voluntary movements. Dyskinesia can be anything from a slight tremor of the hands to an uncontrollable movement of the upper body or lower extremities. Discoordination can also occur internally especially with the respiratory muscles and it often goes unrecognized. Dyskinesia is a symptom of several medical disorders that are distinguished by their underlying cause.

A dopamine antagonist, also known as an anti-dopaminergic and a dopamine receptor antagonist (DRA), is a type of drug which blocks dopamine receptors by receptor antagonism. Most antipsychotics are dopamine antagonists, and as such they have found use in treating schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and stimulant psychosis. Several other dopamine antagonists are antiemetics used in the treatment of nausea and vomiting.

Prochlorperazine, formerly sold under the brand name Compazine among others, is a medication used to treat nausea, migraines, schizophrenia, psychosis and anxiety. It is a less preferred medication for anxiety. It may be taken by mouth, rectally, injection into a vein, or injection into a muscle.

Progabide is an analogue and prodrug of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) used in the treatment of epilepsy. Via conversion into GABA, progabide behaves as an agonist of the GABAA, GABAB, and GABAA-ρ receptors.

Amisulpride is an antiemetic and antipsychotic medication used at lower doses intravenously to prevent and treat postoperative nausea and vomiting; and at higher doses by mouth to treat schizophrenia and acute psychotic episodes. It is sold under the brand names Barhemsys and Solian, Socian, Deniban and others. At very low doses it is also used to treat dysthymia.

Procyclidine is an anticholinergic drug principally used for the treatment of drug-induced parkinsonism, akathisia and acute dystonia, Parkinson's disease, and idiopathic or secondary dystonia.

Asenapine, sold under the brand name Saphris among others, is an atypical antipsychotic medication used to treat schizophrenia and acute mania associated with bipolar disorder as well as the medium to long-term management of bipolar disorder.

Zuclopenthixol, also known as zuclopentixol, is a medication used to treat schizophrenia and other psychoses. It is classed, pharmacologically, as a typical antipsychotic. Chemically it is a thioxanthene. It is the cis-isomer of clopenthixol. Clopenthixol was introduced in 1961, while zuclopenthixol was introduced in 1978.

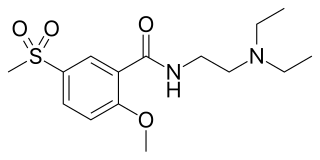

Tiapride is a drug that selectively blocks D2 and D3 dopamine receptors in the brain. It is used to treat a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders including dyskinesia, alcohol withdrawal syndrome, negative symptoms of psychosis, and agitation and aggression in the elderly. A derivative of benzamide, tiapride is chemically and functionally similar to other benzamide antipsychotics such as sulpiride and amisulpride known for their dopamine antagonist effects.

Pleurothotonus, commonly known as Pisa syndrome, is a rare neurological disorder which occurs due to prolonged exposure to antipsychotic drugs. It is characterized by dystonia, and abnormal and sustained involuntary muscle contraction. This may cause twisting or jerking movements of the body or a body part. Although Pisa syndrome develops most commonly in those undergoing long-term treatment with antipsychotics, it has been reported less frequently in patients receiving other medications, such as an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. However, it has also been seen in those with other diseases causing neurodegeneration and in those who are not receiving any medication. The characteristic development of Pisa syndrome consists of two types of dystonia: acute dystonia and tardive dystonia. The underlying pathology of drug-induced Pisa syndrome is very complex, and development may be due to an underlying dopaminergic-cholinergic imbalance, or serotonergic/noradrenergic dysfunction.

Aripiprazole lauroxil, sold under the brand name Aristada, is a long-acting injectable atypical antipsychotic that was developed by Alkermes. It is an N-acyloxymethyl prodrug of aripiprazole that is administered via intramuscular injection once every four to eight weeks for the treatment of schizophrenia. Aripiprazole lauroxil was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 5 October 2015.

References

- ↑ Akagi, Hiroko; Kumar, T Manoj (2002-06-22). "Akathisia: overlooked at a cost". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 324 (7352): 1506–1507. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7352.1506. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1123446 . PMID 12077042.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pierre, JM (2005). "Extrapyramidal symptoms with atypical antipsychotics: incidence, prevention and management". Drug Safety. 28 (3): 191–208. doi:10.2165/00002018-200528030-00002. PMID 15733025. S2CID 41268164.

- ↑ Jeffrey A. Lieberman; T. Scott Stroup; Joseph P. McEvoy; Marvin S. Swartz; Robert A. Rosenheck; Diana O. Perkins; Richard S.E. Keefe; Sonia M. Davis; Clarence E. Davis; Barry D. Lebowitz; Joanne Severe; John K. Hsiao & for the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators (September 22, 2005). "Effectiveness of Antipsychotic Drugs in Patients with Chronic Schizophrenia". N Engl J Med. 353 (12): 1209–1223. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa051688. PMID 16172203.

- ↑ Nevena Divac; Milica Prostran; Igor Jakovcevski & Natasa Cerovac (2014). "Second-Generation Antipsychotics and Extrapyramidal Adverse Effects". BioMed Research International. 2014: 6 pages. doi: 10.1155/2014/656370 . PMC 4065707 . PMID 24995318.

- ↑ Correll C (2014). "Mechanism of Action of Antipsychotic Medications". J Clin Psychiatry. 75 (9): e23. doi:10.4088/jcp.13078tx4c.

- ↑ Moos, DD.; Hansen, DJ. (October 2008). "Metoclopramide and Extrapyramidal Symptoms: A Case Report". Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing. 23 (5): 292–299. doi:10.1016/j.jopan.2008.07.006. PMID 18926476.

- 1 2 Madhusoodanan S, Alexeenko L, Sanders R, Brenner R (2010). "Extrapyramidal symptoms associated with antidepressants—A review of the literature and an analysis of spontaneous reports" (PDF). Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 22 (3): 148–156. PMID 20680187.

- ↑ Ori Scott; Simona Hasal & Helly R. Goez (November 2013) [September 10, 2012]. "Basal Ganglia Injury With Extrapyramidal Presentation: A Complication of Meningococcal Meningitis". J Child Neurol. 28 (11): 1489–1492. doi:10.1177/0883073812457463. PMID 22965562. S2CID 30536341.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Involuntary Movement Disorders (Ch. 18)". Kaufman's Clinical Neurology for Psychiatrists (8th ed.). Elsevier Inc.

- 1 2 "Be Drug Wise: Psychotherapeutic Meds". Educational Global Technologies, Inc. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ↑ Michael J. Peluso; Shôn W. Lewis; Thomas R. E. Barnes; Peter B. Jones (2012). "Extrapyramidal motor side-effects of first- and second-generation antipsychotic drugs". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 200 (5): 387–92. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101485 . PMID 22442101.

- ↑ E. Thomas, Jennifer; Caballero, Joshua; A. Harrington, Catherine (13 October 2015). "The Incidence of Akathisia in the Treatment of Schizophrenia with Aripiprazole, Asenapine and Lurasidone: A Meta-Analysis". Current Neuropharmacology. 13 (5): 681–691. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666150115220221. PMC 4761637 . PMID 26467415.

- ↑ Salem, Haitham; Nagpal, Caesa; Pigott, Teresa; Teixeira, Antonio Lucio (15 June 2017). "Revisiting Antipsychotic-induced Akathisia: Current Issues and Prospective Challenges". Current Neuropharmacology. 15 (5): 789–798. doi:10.2174/1570159X14666161208153644. PMC 5771055 . PMID 27928948.