Related Research Articles

Software testing is the act of checking whether software satisfies expectations.

An embedded system is a computer system—a combination of a computer processor, computer memory, and input/output peripheral devices—that has a dedicated function within a larger mechanical or electronic system. It is embedded as part of a complete device often including electrical or electronic hardware and mechanical parts. Because an embedded system typically controls physical operations of the machine that it is embedded within, it often has real-time computing constraints. Embedded systems control many devices in common use. In 2009, it was estimated that ninety-eight percent of all microprocessors manufactured were used in embedded systems.

In computer engineering, a hardware description language (HDL) is a specialized computer language used to describe the structure and behavior of electronic circuits, most commonly to design ASICs and program FPGAs.

In systems engineering, dependability is a measure of a system's availability, reliability, maintainability, and in some cases, other characteristics such as durability, safety and security. In real-time computing, dependability is the ability to provide services that can be trusted within a time-period. The service guarantees must hold even when the system is subject to attacks or natural failures.

System testing, a.k.a. end-to-end (E2E) testing, is testing conducted on a complete software system.

In programming and software development, fuzzing or fuzz testing is an automated software testing technique that involves providing invalid, unexpected, or random data as inputs to a computer program. The program is then monitored for exceptions such as crashes, failing built-in code assertions, or potential memory leaks. Typically, fuzzers are used to test programs that take structured inputs. This structure is specified, e.g., in a file format or protocol and distinguishes valid from invalid input. An effective fuzzer generates semi-valid inputs that are "valid enough" in that they are not directly rejected by the parser, but do create unexpected behaviors deeper in the program and are "invalid enough" to expose corner cases that have not been properly dealt with.

Fault tolerance is the ability of a system to maintain proper operation in the event of failures or faults in one or more of its components. Any decrease in operating quality is proportional to the severity of the failure, unlike a naively designed system in which even a small failure can lead to total breakdown. Fault tolerance is particularly sought after in high-availability, mission-critical, or even life-critical systems. The ability to maintain functionality when portions of a system break down is referred to as graceful degradation.

Mutation testing is used to design new software tests and evaluate the quality of existing software tests. Mutation testing involves modifying a program in small ways. Each mutated version is called a mutant and tests detect and reject mutants by causing the behaviour of the original version to differ from the mutant. This is called killing the mutant. Test suites are measured by the percentage of mutants that they kill. New tests can be designed to kill additional mutants. Mutants are based on well-defined mutation operators that either mimic typical programming errors or force the creation of valuable tests. The purpose is to help the tester develop effective tests or locate weaknesses in the test data used for the program or in sections of the code that are seldom or never accessed during execution. Mutation testing is a form of white-box testing.

Application security includes all tasks that introduce a secure software development life cycle to development teams. Its final goal is to improve security practices and, through that, to find, fix and preferably prevent security issues within applications. It encompasses the whole application life cycle from requirements analysis, design, implementation, verification as well as maintenance.

Stress testing is a software testing activity that determines the robustness of software by testing beyond the limits of normal operation. Stress testing is particularly important for "mission critical" software, but is used for all types of software. Stress tests commonly put a greater emphasis on robustness, availability, and error handling under a heavy load, than on what would be considered correct behavior under normal circumstances.

Fault Tolerant Messaging in the context of computer systems and networks, refers to a design approach and set of techniques aimed at ensuring reliable and continuous communication between components or nodes even in the presence of errors or failures. This concept is especially critical in distributed systems, where components may be geographically dispersed and interconnected through networks, making them susceptible to various potential points of failure.

Model-based design (MBD) is a mathematical and visual method of addressing problems associated with designing complex control, signal processing and communication systems. It is used in many motion control, industrial equipment, aerospace, and automotive applications. Model-based design is a methodology applied in designing embedded software.

In computing, an emulator is hardware or software that enables one computer system to behave like another computer system. An emulator typically enables the host system to run software or use peripheral devices designed for the guest system. Emulation refers to the ability of a computer program in an electronic device to emulate another program or device.

API testing is a type of software testing that involves testing application programming interfaces (APIs) directly and as part of integration testing to determine if they meet expectations for functionality, reliability, performance, and security. Since APIs lack a GUI, API testing is performed at the message layer. API testing is now considered critical for automating testing because APIs serve as the primary interface to application logic and because GUI tests are difficult to maintain with the short release cycles and frequent changes commonly used with Agile software development and DevOps.

In computer science, robustness is the ability of a computer system to cope with errors during execution and cope with erroneous input. Robustness can encompass many areas of computer science, such as robust programming, robust machine learning, and Robust Security Network. Formal techniques, such as fuzz testing, are essential to showing robustness since this type of testing involves invalid or unexpected inputs. Alternatively, fault injection can be used to test robustness. Various commercial products perform robustness testing of software analysis.

Robustness testing is any quality assurance methodology focused on testing the robustness of software. Robustness testing has also been used to describe the process of verifying the robustness of test cases in a test process. ANSI and IEEE have defined robustness as the degree to which a system or component can function correctly in the presence of invalid inputs or stressful environmental conditions.

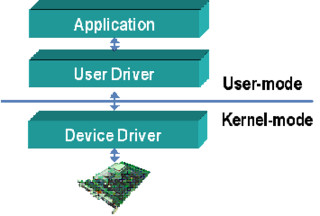

Device drivers are programs which allow software or higher-level computer programs to interact with a hardware device. These software components act as a link between the devices and the operating systems, communicating with each of these systems and executing commands. They provide an abstraction layer for the software above and also mediate the communication between the operating system kernel and the devices below.

Real-time testing is the process of testing real-time computer systems.

Unified Diagnostic Services (UDS) is a diagnostic communication protocol used in electronic control units (ECUs) within automotive electronics, which is specified in the ISO 14229-1. It is derived from ISO 14230-3 (KWP2000) and the now obsolete ISO 15765-3. 'Unified' in this context means that it is an international and not a company-specific standard. By now this communication protocol is used in all new ECUs made by Tier 1 suppliers of Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM), and is incorporated into other standards, such as AUTOSAR. The ECUs in modern vehicles control nearly all functions, including electronic fuel injection (EFI), engine control, the transmission, anti-lock braking system, door locks, braking, window operation, and more.

This article discusses a set of tactics useful in software testing. It is intended as a comprehensive list of tactical approaches to Software Quality Assurance (more widely colloquially known as Quality Assurance and general application of the test method.

References

- ↑ Moradi, Mehrdad; Van Acker, Bert; Vanherpen, Ken; Denil, Joachim (2019). "Model-Implemented Hybrid Fault Injection for Simulink (Tool Demonstrations)". In Chamberlain, Roger; Taha, Walid; Törngren, Martin (eds.). Cyber Physical Systems. Model-Based Design. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 11615. Springer International Publishing. pp. 71–90. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-23703-5_4. ISBN 9783030237035. S2CID 195769468.

- ↑ Shepherd, Carlton; Markantonakis, Konstantinos; Van Heijningen, Nico; Aboulkassimi, Driss; Gaine, Clement; Heckmann, Thibaut; Naccache, David (2021). "Physical fault injection and side-channel attacks on mobile devices: A comprehensive analysis". Computers & Security. 111 (102471). Elsevier: 102471. arXiv: 2105.04454 . doi:10.1016/j.cose.2021.102471. S2CID 236957400.

- ↑ Bar-El, Hagai; Choukri, Hamid; Naccache, David; Tunstall, Michael; Whelan, Claire (2004). "The sorcerer's apprentice guide to fault attacks". Proceedings of the IEEE. 94 (2). IEEE: 370–382. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2005.862424. S2CID 2397174.

- ↑ J. Voas, "Fault Injection for the Masses," Computer, vol. 30, pp. 129–130, 1997.

- 1 2 Kaksonen, Rauli. A Functional Method for Assessing Protocol Implementation Security. 2001.

- ↑ A. Avizienis, J.-C. Laprie, Brian Randell, and C. Landwehr, "Basic Concepts and Taxonomy of Dependable and Secure Computing," Dependable and Secure Computing, vol. 1, pp. 11–33, 2004.

- 1 2 J. V. Carreira, D. Costa, and S. J. G, "Fault Injection Spot-Checks Computer System Dependability," IEEE Spectrum, pp. 50–55, 1999.

- ↑ Benso, Alfredo; Prinetto, Paolo, eds. (2003). Fault Injection Techniques and Tools for Embedded Systems Reliability Evaluation. Frontiers in Electronic Testing. Springer US. ISBN 978-1-4020-7589-6.

- ↑ "Optimizing fault injection in FMI co-simulation through sensitivity partitioning | Proceedings of the 2019 Summer Simulation Conference". dl.acm.org. Retrieved 2020-06-14.

- ↑ Moradi, M., Oakes, B.J., Saraoglu, M., Morozov, A., Janschek, K. and Denil, J., 2020. EXPLORING FAULT PARAMETER SPACE USING REINFORCEMENT LEARNING-BASED FAULT INJECTION.

- ↑ Rickard Svenningsson, Jonny Vinter, Henrik Eriksson and Martin Torngren, "MODIFI: A MODel-Implemented Fault Injection Tool,", Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2010, Volume 6351/2010, 210-222.

- ↑ G. A. Kanawati, N. A. Kanawati, and J. A. Abraham, "FERRARI: A Flexible Software-Based Fault and Error Injection System," IEEE Transactions on Computers, vol. 44, pp. 248, 1995.

- ↑ T. Tsai and R. Iyer, "FTAPE: A Fault Injection Tool to Measure Fault Tolerance," presented at Computing in aerospace, San Antonio; TX, 1995.

- ↑ S. Han, K. G. Shin, and H. A. Rosenberg, "DOCTOR: An IntegrateD SOftware Fault InjeCTiOn EnviRonment for Distributed Real-time Systems," presented at International Computer Performance and Dependability Symposium, Erlangen; Germany, 1995.

- ↑ S. Dawson, F. Jahanian, and T. Mitton, "ORCHESTRA: A Probing and Fault Injection Environment for Testing Protocol Implementations," presented at International Computer Performance and Dependability Symposium, Urbana-Champaign, USA, 1996.

- ↑ Grid-FIT Web-site Archived 2 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ N. Looker, B. Gwynne, J. Xu, and M. Munro, "An Ontology-Based Approach for Determining the Dependability of Service-Oriented Architectures," in the proceedings of the 10th IEEE International Workshop on Object-oriented Real-time Dependable Systems, USA, 2005.

- ↑ N. Looker, M. Munro, and J. Xu, "A Comparison of Network Level Fault Injection with Code Insertion," in the proceedings of the 29th IEEE International Computer Software and Applications Conference, Scotland, 2005.

- ↑ LFI Website

- ↑ Flatag (2020-05-16), Flatag/FIBlock , retrieved 2020-05-16

- ↑ beSTORM product information

- ↑ ExhaustiF SWIFI Tool Site

- ↑ Holodeck product overview Archived 13 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Codenomicon Defensics product overview

- ↑ Mu Service Analyzer

- ↑ Mu Dynamics, Inc.

- ↑ Xception Web Site

- ↑ Critical Software SA

- ↑ Abbasinasab, Ali; Mohammadi, Mehdi; Mohammadi, Siamak; Yanushkevich, Svetlana; Smith, Michael (2011). "Mutant Fault Injection in Functional Properties of a Model to Improve Coverage Metrics". 2011 14th Euromicro Conference on Digital System Design. pp. 422–425. doi:10.1109/DSD.2011.57. ISBN 978-1-4577-1048-3. S2CID 15992130.

- ↑ N. Looker, M. Munro, and J. Xu, "Simulating Errors in Web Services," International Journal of Simulation Systems, Science & Technology, vol. 5, 2004.