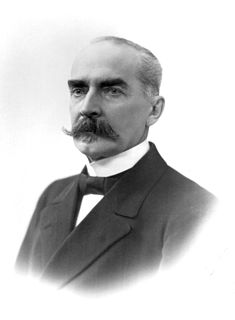

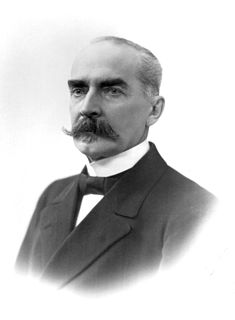

Juho Kusti Paasikivi was the seventh president of Finland (1946–1956). Representing the Finnish Party and the National Coalition Party, he also served as Prime Minister of Finland. In addition to the above, Paasikivi held several other positions of trust, and was an influential figure in Finnish economics and politics for over fifty years.

Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg was a Finnish jurist and academic, which was one of the most important pioneers of republicanism in the country. He was the first president of Finland (1919–1925) and a liberal nationalist.

The Swedish-speaking population of Finland is a linguistic minority in Finland. They maintain a strong identity and are seen either as a separate cultural or ethnic group, while still being Finns, or as a distinct nationality. They speak Finland Swedish, which encompasses both a standard language and distinct dialects that are mutually intelligible with the dialects spoken in Sweden and, to a lesser extent, other Scandinavian languages.

Johan Vilhelm Snellman was an influential Fennoman philosopher and Finnish statesman, ennobled in 1866. He was one of the most important 'awakeners' or promoters of Finnish nationalism, alongside Elias Lönnrot and J. L. Runeberg.

Finland's language strife was a major conflict in mid-19th century Finland. Both the Swedish and Finnish languages were commonly used in Finland at the time, associated with descendants of Swedish colonisation and leading to class tensions among the speakers of the different languages. It became acute in the mid-19th century. The competition was considered to have officially ended when Finnish gained official language status in 1923 and became equal to the Swedish language.

Patriotic People's Movement was a Finnish nationalist and anti-communist political party. IKL was the successor of the previously banned Lapua Movement. It existed from 1932 to 1944 and had an ideology similar to its predecessor, except that IKL participated in elections, although with limited success.

Finnicization is the changing of one's personal names from other languages into Finnish. During the era of National Romanticism in Finland, many people, especially Fennomans, finnicized their previously Swedish family names.

Karl-August Fagerholm was Speaker of Parliament and three times Prime Minister of Finland. Fagerholm became one of the leading politicians of the Social Democrats after the armistice in the Continuation War. As a Scandinavia-oriented Swedish-speaking Finn, he was believed to be more to the taste of the Soviet Union's leadership than his predecessor, Väinö Tanner. Fagerholm's postwar career was, however, marked by fierce opposition from both the Soviet Union and the Communist Party of Finland. He narrowly lost the presidential election to Urho Kekkonen in 1956.

The Finnish Party was a Fennoman conservative political party in the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland and independent Finland. Born out of Finland's language strife in the 1860s, the party sought to improve the position of the Finnish language in Finnish society. Johan Vilhelm Snellman, Yrjö Sakari Yrjö-Koskinen, and Johan Richard Danielson-Kalmari were its ideological leaders. The party's chief organ was the Suometar newspaper, later Uusi Suometar, and its members were sometimes called Suometarians (suomettarelaiset).

Finland declared its independence on 6 December 1917. The formal Declaration of Independence was only part of the long process leading to the independence of Finland.

Peace opposition was a Finnish cross-party movement uniting both bourgeois politicians like Paasikivi, Kekkonen, Sakari Tuomioja etc. and social democrats, aiming at stepping out of the Continuation war and finding a way to conclude peace with the Soviet Union. The number of MPs belonging to this group was rather small at first, but it gained influence as the military situation worsened. After the signing of armistice, Paasikivi established his cabinet, which included members of the previous opposition group.

Baron Yrjö Sakari Yrjö-Koskinen was a friherre, senator, professor, historian, politician and the chairman of the Finnish Party after Johan Vilhelm Snellman. He was a central figure in the fennoman movement. His original name was Georg Zakarias Forsman and his family from his father's side originated from Sweden. He later fennicized his name to Yrjö Sakari Yrjö-Koskinen. He was the husband of Finland's first female author, Theodolinda Hahnsson.

Adolf Ivar Arwidsson was a Finnish political journalist, writer and historian. His writing was critical of Finland's status at the time as a Grand Duchy under the Russian Tsars. Its sharpness cost him his job as a lecturer at The Royal Academy of Turku and he had to emigrate to Sweden, where he continued his political activity. The Finnish national movement considered Arwidsson the mastermind of an independent Finland.

Nationalism was a central force in the History of Finland for the last two centuries. The Finnish national awakening in the mid-19th century was the result of members of the Swedish-speaking upper classes deliberately choosing to promote Finnish culture and language as a means of nation building—i.e. to establish a feeling of unity between all people in Finland including between the ruling elite and the ruled peasantry. The publication in 1835 of the Finnish national epic, the Kalevala, a collection of traditional myths and legends which is the folklore common to the Finns and to the Karelian people, stirred the nationalism that later led to Finland's independence from Russia.

The history of Finnish philosophy ranges from the prehistoric period to contemporary philosophy.