Chinese classic texts or canonical texts or simply dianji (典籍) refers to the Chinese texts which originated before the imperial unification by the Qin dynasty in 221 BC, particularly the "Four Books and Five Classics" of the Neo-Confucian tradition, themselves a customary abridgment of the "Thirteen Classics". All of these pre-Qin texts were written in classical Chinese. All three canons are collectively known as the classics.

The Chinese Rites controversy was a dispute among Catholic missionaries over the religiosity of Confucianism and Chinese rituals during the 17th and 18th centuries. The debate discussed whether Chinese ritual practices of honoring family ancestors and other formal Confucian and Chinese imperial rites qualified as religious rites and were thus incompatible with Catholic belief. The Jesuits argued that these Chinese rites were secular rituals that were compatible with Christianity, within certain limits, and should thus be tolerated. The Dominicans and Franciscans, however, disagreed and reported the issue to Rome.

Joachim Bouvet was a French Jesuit who worked in China, and the leading member of the Figurist movement.

Zhang Juzheng, courtesy name Shuda, pseudonym Taiyue, was a Chinese politician who served as Senior Grand Secretary in the late Ming dynasty during the reigns of the Longqing and Wanli emperors. He represented what might be termed the "new Legalism", aiming to ensure that the gentry worked for the state. Alluding to performance evaluations, he said: "Everyone is talking about real responsibility, but without a clear reward and punishment system, who is going to risk life and hardship for the country?" One of his chief goals was to reform the gentry and rationalize the bureaucracy together with his political rival Gao Gong, who was concerned that offices were providing income with little responsibility. Taking the Hongwu Emperor as his standard and ruling as de facto Prime Minister, Zhang's true historical significance comes from his centralization of existing reforms, positioning the reformative agency of the state over that of the gentry—the "Legalist" idea of the sovereignty of the state.

The Four Books and Five Classics are the authoritative books of Confucianism, written in China before 300 BCE. The Four Books and the Five Classics are the most important classics of Chinese Confucianism.

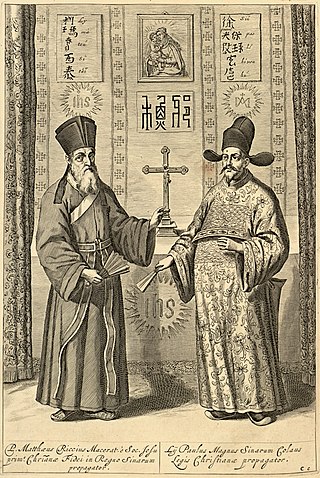

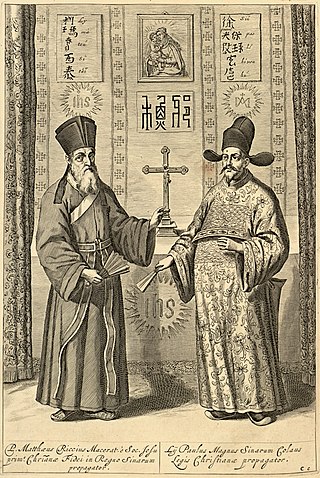

Matteo Ricci was an Italian Jesuit priest and one of the founding figures of the Jesuit China missions. He created the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu, a 1602 map of the world written in Chinese characters. On the 17 December 2022, the Apostolic See declared its recognition of Ricci's 'heroic virtues', thereby bestowing upon him the honorific of Venerable.

Joseph Henri Marie de Prémare was a Jesuit missionary to China. Born in Cherbourg, he departed for China in 1698, and worked as a missionary in Guangxi.

Missionary work of the Catholic Church has often been undertaken outside the geographically defined parishes and dioceses by religious orders who have people and material resources to spare, and some of which specialized in missions. Eventually, parishes and dioceses would be organized worldwide, often after an intermediate phase as an apostolic prefecture or apostolic vicariate. Catholic mission has predominantly been carried out by the Latin Church in practice.

This is a list of selected references for Christianity in China.

The Three Pillars of Chinese Catholicism refer to three Chinese converts to Christianity, during the 16th and 17th century Jesuit China missions:

Prospero Intorcetta (1625-1696), known to the Chinese as Yin Duoze, was an Italian Jesuit missionary to the Qing Empire. The first to translate the works of Confucius in Europe.

Jean-François Foucquet S.J., also Jean-François Fouquet, was a Burgundy French Jesuit, bishop and scientist who was active in the Jesuit China missions for 22 years. He also was Titular Bishop of Eleutheropolis in Macedonia (1725–1741).

Yang Guangxian was a Confucian writer and astronomer who was the head of the Bureau of Astronomy from 1665 to 1669.

Álvaro de Semedo, was a Portuguese Jesuit priest and missionary in China.

De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Societate Jesu ... is a book based on an Italian manuscript written by the most important founding figure of the Jesuit China mission, Matteo Ricci (1552–1610), expanded and translated into Latin by his colleague Nicolas Trigault (1577–1628). The book was first published in 1615 in Augsburg.

Li Yingshi was a Ming Chinese military officer, scientist, astrologer and feng shui practicer that was converted to Christianity. He was converted to Catholicism by Matteo Ricci and Diego de Pantoja, the first two Jesuits to establish themselves in Beijing. He then became a zealous Christian.

David Emil Mungello is an American historian on the cultural interaction between Europe and China since 1550. He has written on the introduction of Christianity into China and the reception of Confucianism into Europe. He is recognized as one of the leading modern authorities on the Jesuit missions in China. He has also written on the history of queer Western men in China.

The history of the missions of the Jesuits in China is part of the history of relations between China and the Western world. The missionary efforts and other work of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, between the 16th and 17th century played a significant role in continuing the transmission of knowledge, science, and culture between China and the West, and influenced Christian culture in Chinese society today.

Political theology in China includes responses from Chinese government leaders, scholars, and religious leaders who deal with the relationship between religion and politics. For two millennia, this was organized based on a Confucian understanding of religion and politics, often discussed in terms of Confucian political philosophy. At various points throughout its history, Chinese Buddhism presented an alternative to the political import of Confucianism. However, since the mid-twentieth century, communist understandings of religion have dominated the discourse.

François Noël was a Flemish Jesuit poet, dramatist, and missionary to the Qing Empire. Nöel unsuccessfully testified in support of Chinese converts to Catholicism retaining ancestral veneration during the Chinese Rites controversy but also opposed incorporating other elements of Confucianism into Catholic practice. He also achieved notability for translating several Chinese texts for European audiences.