The Kalevala is a 19th-century work of epic poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot from Karelian and Finnish oral folklore and mythology, telling an epic story about the Creation of the Earth, describing the controversies and retaliatory voyages between the peoples of the land of Kalevala called Väinölä and the land of Pohjola and their various protagonists and antagonists, as well as the construction and robbery of the epic mythical wealth-making machine Sampo.

Ukko, Äijä[ˈæi̯jæ] or Äijö[ˈæi̯jø], parallel to Uku in Estonian mythology, is the god of the sky, weather, harvest and thunder in Finnish mythology.

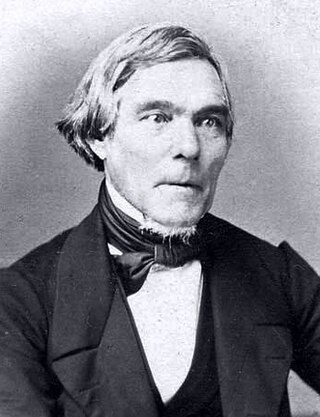

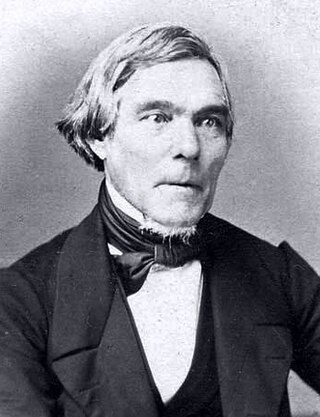

Elias Lönnrot was a Finnish physician, philologist and collector of traditional Finnish oral poetry. He is best known for creating the Finnish national epic, Kalevala, (1835, enlarged 1849), from short ballads and lyric poems gathered from the Finnish oral tradition during several expeditions in Finland, Russian Karelia, the Kola Peninsula and Baltic countries.

Hiisi is a term in Finnic mythologies, originally denoting sacred localities and later on various types of mythological entities.

Karelia is a historical province of Finland which Finland partly ceded to the Soviet Union after the Winter War of 1939–40. The Finnish Karelians include the present-day inhabitants of North and South Karelia and the still-surviving evacuees from the ceded territories. Present-day Finnish Karelia has 315,000 inhabitants. The more than 400,000 evacuees from the ceded territories re-settled in various parts of Finland.

East Karelia, also rendered as Eastern Karelia or Russian Karelia, is a name for the part of Karelia that since the Treaty of Stolbova in 1617 has remained Eastern Orthodox under Russian supremacy. It is separate from the western part of Karelia, called Finnish Karelia or historically Swedish Karelia. Most of East Karelia has become part of the Republic of Karelia within the Russian Federation. It consists mainly of the old historical regions of Viena and Aunus.

Finnish paganism is the indigenous pagan religion in Finland and Karelia prior to Christianisation. It was a polytheistic religion, worshipping a number of different deities. The principal god was the god of thunder and the sky, Ukko; other important gods included Jumo (Jumala), Ahti, and Tapio. Jumala was a sky god; today, the word "Jumala" refers to all gods in general. Ahti was a god of the sea, waters and fish. Tapio was the god of forests and hunting.

Greater Finland, an irredentist and nationalist idea, emphasized territorial expansion of Finland. The most common concept of Greater Finland saw the country as defined by natural borders encompassing the territories inhabited by Finns and Karelians, ranging from the White Sea to Lake Onega and along the Svir River and Neva River—or, more modestly, the Sestra River—to the Gulf of Finland. Some proponents also included the Torne Valley, Ingria, and Estonia.

Finnish literature refers to literature written in Finland. During the European early Middle Ages, the earliest text in a Finnic language is the unique thirteenth-century Birch bark letter no. 292 from Novgorod. The text was written in Cyrillic and represented a dialect of Finnic language spoken in Russian Olonets region. The earliest texts in Finland were written in Swedish or Latin during the Finnish Middle Age. Finnish-language literature was slowly developing from the 16th century onwards, after written Finnish was established by the Bishop and Finnish Lutheran reformer Mikael Agricola (1510–1557). He translated the New Testament into Finnish in 1548.

Loviatar is a blind daughter of Tuoni, the god of death in Finnish mythology and his spouse Tuonetar, the queen of the underworld. Loviatar is regarded as a goddess of death and disease. In Runo 45 of the Kalevala, Loviatar is impregnated by a great wind and gives birth to nine sons, the Nine diseases. In other folk songs, she gives birth to a tenth child, who is a girl.

Elements of a Proto-Uralic religion can be recovered from reconstructions of the Proto-Uralic language.

Kanteletar is a collection of Finnish folk poetry compiled by Elias Lönnrot. It is considered to be a sister collection to the Finnish national epic Kalevala. The poems of Kanteletar are based on the trochaic tetrameter, generally referred to as "Kalevala metre".

Tietäjä is a magically powerful figure in traditional Finno-Karelian culture, whose supernatural powers arise from his great knowledge.

Kalevala Day, known as Finnish Culture Day by its other official name, is celebrated each 28 February in honor of the Finnish national epic, Kalevala. The day is one of the official flag flying days in Finland.

Folklore of Finland refers to traditional and folk practices, technologies, beliefs, knowledge, attitudes and habits in Finland. Finnish folk tradition includes in a broad sense all Finnish traditional folk culture. Folklore is not new, commercial or foreign contemporary culture, or the so-called "high culture". In particular, rural traditions have been considered in Finland as folklore.

Suomen kansan vanhat runot, or SKVR, is an edition of traditional Finnic-language verse containing around 100,000 different songs, and including the majority of the songs that were the sources of the Kalevala and related poetry. The collection is available, free, online.

Synty is an important concept in Finnish mythology. Syntysanat ('origin-words') or syntyloitsut ('origin-charms') provide an explanatory, mythical account of the origin of a phenomenon, material, or species, and were an important part of traditional Finno-Karelian culture, particularly in healing rituals. Although much in the Finnish traditional charms is paralleled elsewhere, 'the role of aetiological and cosmogonic myths' in Finnic tradition 'appears exceptional in Eurasia'. The major study remains that by Kaarle Krohn, published in 1917.

The corpus of traditional riddles from the Finnic-speaking world is fairly unitary, though eastern Finnish-speaking regions show particular influence of Russian Orthodox Christianity and Slavonic riddle culture. The Finnish for 'riddle' is arvoitus, related to the verb arvata and arpa.

Voknavolok is a rural locality under the administrative jurisdiction of the Town of Kostomuksha of the Republic of Karelia, Russia. Population: 427 (2010 Census).

Frog coffins are burials of frogs in miniature coffins in Finland for the purposes of folk magic. These coffins are known from finds secreted in churches, as well as from references to their use in folk magic at other locations.