The history of Sudan refers to the territory that today makes up Republic of the Sudan and the state of South Sudan, which became independent in 2011. The territory of Sudan is geographically part of a larger African region, also known by the term "Sudan". The term is derived from Arabic: بلاد السودان bilād as-sūdān, or "land of the black people", and has sometimes been used more widely referring to the Sahel belt of West and Central Africa.

Gaafar Muhammad an-Nimeiry was a Sudanese military officer and politician who served as the fourth head of state of Sudan from 1969 to 1985, first as Chairman of the National Revolutionary Command Council and then as President.

The Second Sudanese Civil War was a conflict from 1983 to 2005 between the central Sudanese government and the Sudan People's Liberation Army. It was largely a continuation of the First Sudanese Civil War of 1955 to 1972. Although it originated in southern Sudan, the civil war spread to the Nuba mountains and the Blue Nile. It lasted for almost 22 years and is one of the longest civil wars on record. The war resulted in the independence of South Sudan 6 years after the war ended.

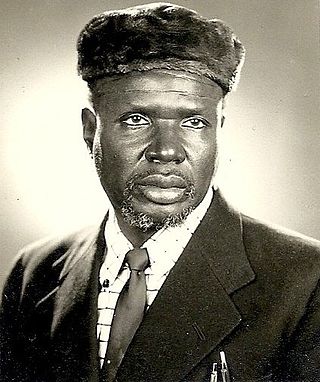

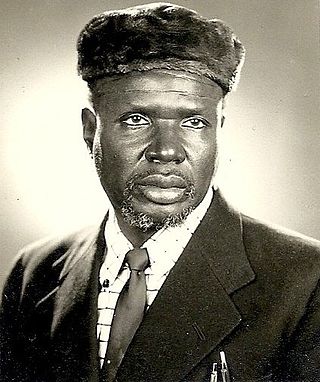

General Ibrahim Abboud was a Sudanese political figure who served as the head of state of Sudan between 1958 and 1964 and as President of Sudan in 1964; however, he soon resigned, ending Sudan's first period of military rule. A career soldier, Abboud served in World War II in Egypt and Iraq. In 1949, Abboud became the deputy Commander in Chief of the Sudanese military. Upon independence, Abboud became the Commander in Chief of the Military of Sudan.

Salva Kiir Mayardit, also known as Salva Kiir, is a South Sudanese politician who has been the President of South Sudan since its independence on 9 July 2011. Prior to independence, he was the President of the Government of Southern Sudan, as well as First Vice President of Sudan, from 2005 to 2011. He was named Commander-in-Chief of the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) in 2005, following the death of John Garang.

The Anyanya were a southern Sudanese separatist rebel army formed during the First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972). A separate movement that rose during the Second Sudanese Civil War were, in turn, called Anyanya II. Anyanya means "snake venom" in the Ma'di language.

Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon is a South Sudanese politician who served as the First Vice President of South Sudan.

The Sudan People's Liberation Movement is a political party in South Sudan. It was initially founded as the political wing of the Sudan People's Liberation Army in 1983. On January 9, 2005 the SPLA, the SPLM and the Government of Sudan signed the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, ending the civil war. SPLM then obtained representation in the Government of Sudan, and was the main constituent of the Government of the then semi-autonomous Southern Sudan. When South Sudan became a sovereign state on 9 July 2011, SPLM became the ruling party of the new republic. SPLM branches in Sudan separated themselves from SPLM, forming the Sudan People's Liberation Movement–North. Further factionalism appeared as a result of the 2013–2014 South Sudanese Civil War, with President Salva Kiir leading the SPLM-Juba and former Vice President Riek Machar leading the Sudan People's Liberation Movement-in-Opposition.

Joseph Lagu is a South Sudanese military figure and politician. He belongs to the Madi ethnic group of Eastern Equatoria, South Sudan.

On 25 May 1969, several young officers calling themselves the Free Officers Movement seized power in Sudan in a coup d'état and started the Nimeiry era, also called the May Regime, in the history of Sudan. At the conspiracy's core were nine officers led by Colonel Gaafar Nimeiry, who had been implicated in plots against the Abboud regime. Nimeiry's coup preempted plots by other groups, most of which involved army factions supported by the Sudanese Communist Party (SCP), Arab nationalists, or conservative religious groups. He justified the coup on the grounds that civilian politicians had paralyzed the decision-making process, had failed to deal with the country's economic and regional problems, and had left Sudan without a permanent constitution.

Anyanya II is the name taken in 1978 by a group of the 64 tribes of South Sudan dissidents who took up arms in All of Sudan. The name implies continuity with the Anyanya, or Anya-Nya, movement of the First Sudanese Civil War (1955-1972).

The South Sudan People's Defence Forces (SSPDF), formerly the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), is the army of the Republic of South Sudan. The SPLA was founded as a guerrilla movement against the government of Sudan in 1983 and was a key participant of the Second Sudanese Civil War, led by John Garang. After Garang's death in 2005, Salva Kiir was named the SPLA's new Commander-in-Chief. As of 2010, the SPLA was divided into divisions of 10,000–14,000 soldiers.

The Simba rebellion, also known as the Orientale revolt, was a regional uprising which took place in the Democratic Republic of the Congo between 1963 and 1965 in the wider context of the Congo Crisis and the Cold War. The rebellion, located in the east of the country, was led by the followers of Patrice Lumumba, who had been ousted from power in 1960 by Joseph Kasa-Vubu and Joseph-Désiré Mobutu and subsequently killed in January 1961 in Katanga. The rebellion was contemporaneous with the Kwilu rebellion led by fellow Lumumbist Pierre Mulele in central Congo.

Rolf Steiner is a German retired mercenary. He began his military career as a French Foreign Legion paratrooper and saw combat in Vietnam, Egypt, and Algeria. Steiner rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel commanding the 4th Commando Brigade in the Biafran Army during the Nigerian Civil War, and later fought with the Anyanya rebels in southern Sudan.

William Deng Nhial was the political leader of the Sudan African National Union (SANU), from 1962 to 1968. He was elected unopposed. He was one of founders of the military wing of the Anyanya fighting for the independence of southern Sudan. He was ambushed and killed by Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) on 9 May 1968 at Cueibet, on his way from Rumbek to Tonj. The Sudanese government denied having authorised his assassination. Although no investigation was conducted, eyewitnesses at Cueibet village and an SANU investigation committee confirmed the SAF's part in his death.

Kawac Makuei Mayar Kawac is a politician from South Sudan who was a leader in the Anyanya I independence movement during the First Sudanese Civil War (1955-1972) and in the Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) during the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005).

Gordon Muortat Mayen Maborjok (1922–2008) was a South Sudanese veteran politician and an advocate for the rights and freedom of the South Sudanese people. He was the President of the Nile Provisional Government (NPG) which led the Anyanya; Southern Sudan's first armed resistance to Khartoum which started in 1955. Muortat also served as Vice-President of the Southern Front (SF) and Foreign Minister in the Southern Sudan Provisional Government (SSPG).

Operation Thunderbolt was the codename for a military offensive by the South Sudanese SPLA rebel group and its allies during the Second Sudanese Civil War. The operation aimed at conquering several towns in Western and Central Equatoria, most importantly Yei, which served as strongholds for the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and helped the Sudanese government to supply its allies, the Ugandan insurgents of the WNBF and UNRF (II) based in Zaire. These pro-Sudanese forces were defeated and driven from Zaire by the SPLA and its allies, namely Uganda and the AFDL, in course of the First Congo War, thus allowing the SPLA launch Operation Thunderbolt from the Zairian side of the border. Covertly supported by expeditionary forces from Uganda, Ethiopia, and Eritrea, the SPLA's offensive was a major success, with several SAF garrison towns falling to the South Sudanese rebels in a matter of days. Yei was encircled and put under siege on 11 March 1997. At the same time, a large group of WNBF fighters as well as SAF, FAZ, and ex-Rwandan Armed Forces soldiers was trying to escape from Zaire to Yei. The column was ambushed and destroyed by the SPLA, allowing it to capture Yei shortly afterward. Following this victory, the South Sudanese rebels continued their offensive until late April, capturing several other towns in Equatoria and preparing further anti-government campaigns.

The War of the Peters was a conflict primarily fought between the forces of Peter Par Jiek and Peter Gadet from June 2000 to August 2001 in Unity State, Sudan. Though both were leaders of local branches of larger rebel groups that were involved in the Second Sudanese Civil War, the confrontation between the two commanders was essentially a private war. As Par and Gadet battled each other, the Sudanese government exploited the inter-rebel conflict as part of a divide and rule strategy, aimed at weakening the rebellion at large and allowing for the extraction of valuable oil in Unity State. In the end, Gadet and Par reconciled when their respective superiors agreed to merge the SPDF and SPLA.

The Torit mutiny was an insurrection that took place in August 1955 in and around Torit, Equatoria, but quickly spread to other southern cities such as Juba, Yei, and Maridi. The rebellion began when a group of officers from No. 2 Company, Equatoria Corps, led by Daniel Jumi Tongun and Marko Rume, both of the Karo ethnic group, mutinied against the British administration on August 18. The immediate causes of the mutiny were a trial of a southern member of the national assembly and an allegedly false telegram urging northern administrators in the South to oppress southerners. Although the insurrection was suppressed, it ushered in a period of instability characterized by guerrilla activity, banditry, and political tensions between north and south that eventually escalated to full-scale civil war with the Anyanya rebellion in 1963.