The economy of Vietnam is a mixed socialist-oriented market economy, which is the 36th-largest in the world as measured by nominal gross domestic product (GDP) and 26th-largest in the world as measured by purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2022. Vietnam is a member of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the World Trade Organization.

Lê Duẩn was a Vietnamese communist politician. He rose in the party hierarchy in the late 1950s and became General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam (VCP) at the 3rd National Congress in 1960. He continued Hồ Chí Minh's policy of ruling through collective leadership. From the mid-1960s until his own death in 1986, he was the top decision-maker in Vietnam.

The Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), also known as the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP), is the founding and sole legal party of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Founded in 1930 by Hồ Chí Minh, the CPV became the ruling party of North Vietnam in 1954 and then all of Vietnam after the collapse of the South Vietnamese government following the Fall of Saigon in 1975. Although it nominally exists alongside the Vietnamese Fatherland Front, it maintains a unitary government and has centralized control over the state, military, and media. The supremacy of the CPV is guaranteed by Article 4 of the national constitution. The Vietnamese public generally refer to the CPV as simply "the Party" or "our Party".

Đỗ Mười was a Vietnamese communist politician. He rose in the party hierarchy in the late 1940s, became Chairman of the Council of Ministers in 1988 and was elected General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) at the 7th Congress in 1991. He continued his predecessor's policy of ruling through a collective leadership and Nguyễn Văn Linh's policy of economic reform. He was elected for two terms as General Secretary, but left office in 1997 at the 3rd plenum of the 8th Central Committee during his second term.

Đổi Mới is the name given to the economic reforms initiated in Vietnam in 1986 with the goal of creating a "socialist-oriented market economy". The term đổi mới itself is a general term with wide use in the Vietnamese language meaning "innovate" or "renovate". However, the Đổi Mới Policy refers specifically to these reforms that sought to transition Vietnam from a command economy to a socialist-oriented market economy.

The economic history of China describes the changes and developments in China's economy from the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 to the present day.

The 10th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam was held in Ba Đình Hall, Hanoi from 18 to 25 April 2006. The congress occurs every five years. 1,176 delegates represented the party's 3 million members. At the 13th plenum of the Central Committee, held before the congress, it was decided that eight members of the Communist Party's 9th Politburo had to retire. While certain segments within and outside the Politburo were skeptical, the decision was implemented. Because of party rules, the congress was not empowered to elect the general secretary, and it held a survey on whom the delegates wanted to be appointed General Secretary. The first plenum of the Central Committee, held in the immediate aftermath of the congress, re-elected Nông Đức Mạnh as general secretary.

On the eve of the 1921 revolution, Mongolia had an underdeveloped, stagnant economy based on nomadic animal husbandry. Farming and industry were almost nonexistent; transportation and communications were primitive; banking, services, and trade were almost exclusively in the hands of Chinese or other foreigners. Most of the people were illiterate nomadic herders, and a large part of the male labour force lived in the monasteries, contributing little to the economy. Property in the form of livestock was owned primarily by aristocrats and monasteries; ownership of the remaining sectors of the economy was dominated by Chinese or other foreigners. Mongolia's new rulers thus were faced with a daunting task in building a modern, socialist economy.

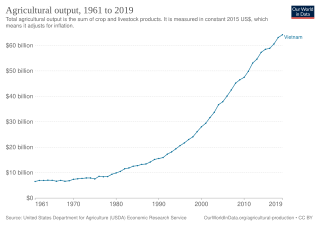

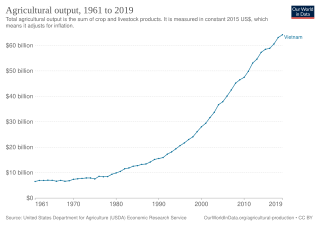

In 2004, agriculture and forestry accounted for 21.8 percent of Vietnam's gross domestic product (GDP), and between 1994 and 2004, the sector grew at an annual rate of 4.1 percent. Agriculture's share of economic output has declined in recent years, falling as a share of GDP from 42% in 1989 to 26% in 1999, as production in other sectors of the economy has risen. However, agricultural employment was much higher than agriculture's share of GDP; in 2005, approximately 60 percent of the employed labor force was engaged in agriculture, forestry, and fishing. Agricultural products accounted for 30 percent of exports in 2005. The relaxation of the state monopoly on rice exports transformed the country into the world's second or third largest rice exporter. Other cash crops are coffee, cotton, peanuts, rubber, sugarcane, and tea.

Industrialisation in the Soviet Union was a process of accelerated building-up of the industrial potential of the Soviet Union to reduce the economy's lag behind the developed capitalist states, which was carried out from May 1929 to June 1941.

Cambodia was a farming area in the first and second millennia BC. States in the area engaged in trade in the Indian Ocean and exported rice surpluses. Complex irrigation systems were built in the 9th century. The French colonial period left the large feudal landholdings intact. Roads and a railway were built, and rubber, rice and corn grown. After independence Sihanouk pursued a policy of economic independence, securing aid and investment from a number of countries.

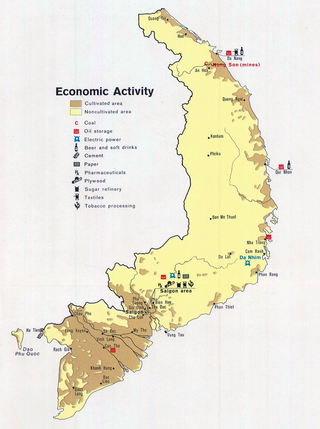

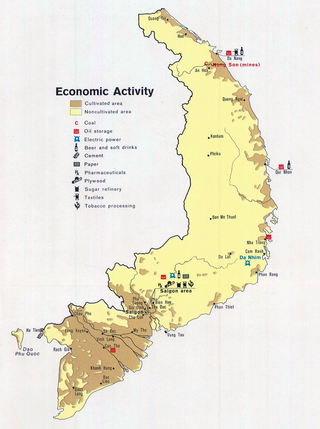

The Republic of Vietnam had an open market economy mostly based on services, agriculture, and aid from the United States. Though formally a free market economy, economic development was based largely on five-year economic plans or four-year economic plans. Its economy stayed stable in the 10 first years, then it faced difficulties due to the escalation of the Vietnam War, which led to unsteady economic growth, high state budget deficits, high inflation, and trade deficits. The South Vietnamese government conducted land reforms twice. The United States played an important role in this economy through economic and technical aid, and trade.

Until French colonization in the middle of the 19th century, the economy of Vietnam was mainly agrarian and village-oriented. However, French colonizers deliberately developed the regions differently, designating the South for agricultural production and the North for manufacturing. Though the plan exaggerated regional divisions, the development of exports--coal from the North, rice from the South—and the importation of French manufactured goods stimulated internal commerce.

Vietnam's foreign trade has been growing fast since state controls were relaxed in the 1990s. The country imports machinery, refined petroleum, and steel; it exports crude oil, textiles and garments, and footwear. The balance of trade has in the past been positive but recent statistics (2004) showed that it was negative.

Manufacturing in Vietnam after reunification followed a pattern that was initially the reverse of the record in agriculture; it showed recovery from a depressed base in the early postwar years. However, this recovery stopped in the late 1970s as the war in Cambodia and the threat from China caused the government to redirect food, finance, and other resources to the military. This move worsened shortages and intensified old bottlenecks. At the same time, the invasion of Cambodia cost Vietnam urgent foreign economic support. China's attack on Vietnam in 1979 compounded industrial problems by damaging important industrial facilities in the North, particularly a major steel plant and an apatite mine.

The Five-Year Plans are a series of social and economic development initiatives issued by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) since 1953 in the People's Republic of China. Since 1949, the CCP has shaped the Chinese economy through the plenums of its Central Committee and national congresses. The party plays a leading role in establishing the foundations and principles of Chinese communism, mapping strategies for economic development, setting growth targets, and launching reforms.

The 7th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam was held in Ba Đình Hall, Hanoi from 24–27 June 1991. The congress occurs once every five years. A total of 1,176 delegates represented the party's 2.1 million card-carrying members.

The 6th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) was held in Ba Đình Hall, Hanoi, between 15 and 18 December 1986. 1,129 delegates represented the party's estimated 1,900,000 members. The congress occurs once every five years. Preparations for the 6th National Congress began with 8th plenum of the 5th Central Committee and ended with the 10th plenum, which lasted 19 days. After the 10th plenum, local and provincial party organizations began electing delegates to the congress as well as updating party documents.

The New Economic Policy (NEP) was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, both subject to state control", while socialized state enterprises would operate on "a profit basis".

The economy of the Soviet Union was based on state ownership of the means of production, collective farming, and industrial manufacturing. An administrative-command system managed a distinctive form of central planning. The Soviet economy was characterized by state control of investment, a dependence on natural resources, shortages of many consumer goods, little foreign trade, public ownership of industrial assets, macroeconomic stability, negligible unemployment and high job security.