Christopher Wolfgang John Alexander was an Austrian-born British-American architect and design theorist. He was an emeritus professor at the University of California, Berkeley. His theories about the nature of human-centered design have affected fields beyond architecture, including urban design, software, and sociology. Alexander designed and personally built over 100 buildings, both as an architect and a general contractor.

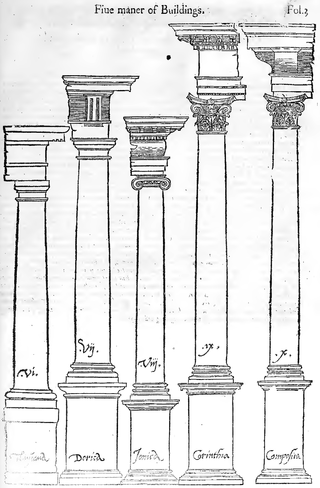

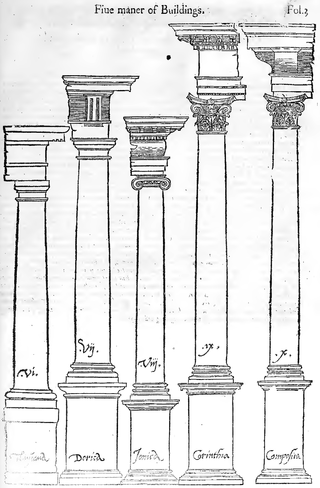

Classical architecture usually denotes architecture which is more or less consciously derived from the principles of Greek and Roman architecture of classical antiquity, or sometimes more specifically, from the works of the Roman architect Vitruvius. Different styles of classical architecture have arguably existed since the Carolingian Renaissance, and prominently since the Italian Renaissance. Although classical styles of architecture can vary greatly, they can in general all be said to draw on a common "vocabulary" of decorative and constructive elements. In much of the Western world, different classical architectural styles have dominated the history of architecture from the Renaissance until World War II. Classical architecture continues to inform many architects.

Classicism, in the arts, refers generally to a high regard for a classical period, classical antiquity in the Western tradition, as setting standards for taste which the classicists seek to emulate. In its purest form, classicism is an aesthetic attitude dependent on principles based in the culture, art and literature of ancient Greece and Rome, with the emphasis on form, simplicity, proportion, clarity of structure, perfection, restrained emotion, as well as explicit appeal to the intellect. The art of classicism typically seeks to be formal and restrained: of the Discobolus Sir Kenneth Clark observed, "if we object to his restraint and compression we are simply objecting to the classicism of classic art. A violent emphasis or a sudden acceleration of rhythmic movement would have destroyed those qualities of balance and completeness through which it retained until the present century its position of authority in the restricted repertoire of visual images." Classicism, as Clark noted, implies a canon of widely accepted ideal forms, whether in the Western canon that he was examining in The Nude (1956).

German idealism is a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s, and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary politics of the Enlightenment. The period of German idealism after Kant is also known as post-Kantian idealism or simply post-Kantianism. One scheme divides German idealists into transcendental idealists, associated with Kant and Fichte, and absolute idealists, associated with Schelling and Hegel.

Mathematics and architecture are related, since, as with other arts, architects use mathematics for several reasons. Apart from the mathematics needed when engineering buildings, architects use geometry: to define the spatial form of a building; from the Pythagoreans of the sixth century BC onwards, to create forms considered harmonious, and thus to lay out buildings and their surroundings according to mathematical, aesthetic and sometimes religious principles; to decorate buildings with mathematical objects such as tessellations; and to meet environmental goals, such as to minimise wind speeds around the bases of tall buildings.

Originating in ancient India, Vastu Shastra is a traditional Hindu system of architecture based on ancient texts that describe principles of design, layout, measurements, ground preparation, space arrangement, and spatial geometry. The designs aim to integrate architecture with nature, the relative functions of various parts of the structure, and ancient beliefs utilising geometric patterns (yantra), symmetry, and directional alignments.

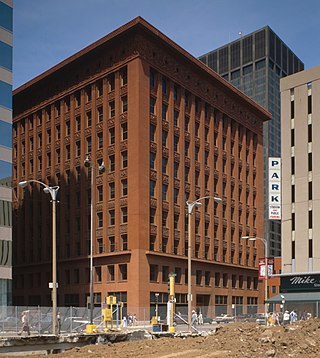

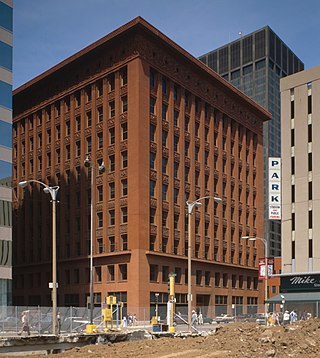

Form follows function is a principle of design associated with late 19th- and early 20th-century architecture and industrial design in general, which states that the shape of a building or object should primarily relate to its intended function or purpose.

Picturesque is an aesthetic ideal introduced into English cultural debate in 1782 by William Gilpin in Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the Summer of the Year 1770, a practical book which instructed England's leisured travellers to examine "the face of a country by the rules of picturesque beauty". Picturesque, along with the aesthetic and cultural strands of Gothic and Celticism, was a part of the emerging Romantic sensibility of the 18th century.

Perfection is a state, variously, of completeness, flawlessness, or supreme excellence.

The Primitive Hut is a concept that explores the origins of architecture and its practice. The concept explores the anthropological relationship between human and the natural environment as the fundamental basis for the creation of architecture. The idea of The Primitive Hut contends that the ideal architectural form embodies what is natural and intrinsic.

This is a history of aesthetics.

Architectural theory is the act of thinking, discussing, and writing about architecture. Architectural theory is taught in all architecture schools and is practiced by the world's leading architects. Some forms that architecture theory takes are the lecture or dialogue, the treatise or book, and the paper project or competition entry. Architectural theory is often didactic, and theorists tend to stay close to or work from within schools. It has existed in some form since antiquity, and as publishing became more common, architectural theory gained an increased richness. Books, magazines, and journals published an unprecedented number of works by architects and critics in the 20th century. As a result, styles and movements formed and dissolved much more quickly than the relatively enduring modes in earlier history. It is to be expected that the use of the internet will further the discourse on architecture in the 21st century.

High-tech architecture, also known as structural expressionism, is a type of late modernist architecture that emerged in the 1970s, incorporating elements of high tech industry and technology into building design. High-tech architecture grew from the modernist style, utilizing new advances in technology and building materials. It emphasizes transparency in design and construction, seeking to communicate the underlying structure and function of a building throughout its interior and exterior. High-tech architecture makes extensive use of aluminium, steel, glass, and to a lesser extent concrete, as these materials were becoming more advanced and available in a wider variety of forms at the time the style was developing – generally, advancements in a trend towards lightness of weight.

Inspiration is an unconscious burst of creativity in a literary, musical, or visual art and other artistic endeavours. The concept has origins in both Hellenism and Hebraism. The Greeks believed that inspiration or "enthusiasm" came from the muses, as well as the gods Apollo and Dionysus. Similarly, in the Ancient Norse religions, inspiration derives from the gods, such as Odin. Inspiration is also a divine matter in Hebrew poetics. In the Book of Amos the prophet speaks of being overwhelmed by God's voice and compelled to speak. In Christianity, inspiration is a gift of the Holy Spirit.

Carlo Lodoli was an Italian architectural theorist, Franciscan priest, mathematician and teacher, whose work anticipated modernist notions of functionalism and truth to materials. He claimed that architectural forms and proportions should be derived from the abilities of the material being used. He is sometimes referred to as the Socrates of architecture since his own writings have been lost his theories are only known from the works of others. Together with architects and architectural theorists including Claude Perrault, Abbé Jean-Louis de Cordemoy, Abbé Marc-Antoine Laugier, Lodoli articulated a rational architecture which challenged the prevailing Baroque and Rococo styles.

The Abbé Jean-Louis de Cordemoy (1655–1714) was a French architectural historian, prior of St-Nicolas at La-Ferté-sous-Jouarre (Seine-et-Marne), and a canon at St-Jean-des-Vignes, Soissons (Aisne). His Nouveau Traité de toute l’architecture was amongst the first studies of ecclesiastical architecture, wherein he praised the Gothic style for its clear expression of structure. Influenced by Michel de Frémin and Claude Perrault his ideas of ordonnance, disposition and bienséance as expressions of integrity to nature and structure were early precursors of the modern concepts of functionalism and truth to materials. He had a considerable influence on 18th-century architectural theory, especially Antoine Desgodetz, Marc-Antoine Laugier, de la Hire and Boffrand. He also participated in an acrimonious debate with the engineer Amédée-François Frézier regarding sacred architecture in the Jesuit periodical Mémoires de Trévoux, a skirmish in the Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns.

Architectural design values make up an important part of what influences architects and designers when they make their design decisions. However, architects and designers are not always influenced by the same values and intentions. Value and intentions differ between different architectural movements. It also differs between different schools of architecture and schools of design as well as among individual architects and designers.

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and constructing buildings or other structures. The term comes from Latin architectura; from Ancient Greek ἀρχιτέκτων (arkhitéktōn) 'architect'; from ἀρχι- (arkhi-) 'chief', and τέκτων (téktōn) 'creator'. Architectural works, in the material form of buildings, are often perceived as cultural symbols and as works of art. Historical civilisations are often identified with their surviving architectural achievements.

'Negative Approach to Urban Planning', also known as "reversed planning" or simply "negative planning" is a landscape urbanism approach to urban planning. It is a new concept and terminology introduced by Chinese landscape architect, Professor of Peking University YU Kongjian. Yu argued that among other issues, the degrading environmental and ecological situations, low performance scrambled city form, and the loss of cultural identity in Beijing have proved that the conventional "population projection-urban infrastructure-land use" approach and the architectural urbanism approach to urban growth planning failed to meet the challenges of swift urbanisation and sustainability issues in China in general, and Beijing in particular. The negative approach defines an urban growth and urban form based on Ecological Infrastructure (EI). This approach has evolved from the pre-scientific model of Feng-shui as the sacred landscape setting for human settlement, the nineteenth century notion of greenways as urban recreational infrastructure, the early twentieth century idea of green belts as urban form makers, and the late twentieth century notion of ecological networks and EI as a biological preservation framework. EI is composed of critical landscape elements and structure that are strategically identified as Landscape Security Patterns to safeguard natural assets and ecosystems services, essential for sustaining human society. EI is strategically planned and developed using less land but more efficiently preserving the Ecosystem service. It distinguishes itself from other theories as it is practical way of solving urban and rural planning problems in quickly developing regions.

An architectural style is a classification of buildings based on a set of characteristics and features, including overall appearance, arrangement of the components, method of construction, building materials used, form, size, structural design, and regional character.