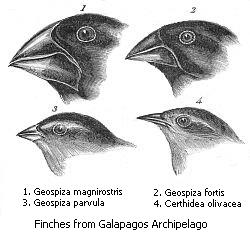

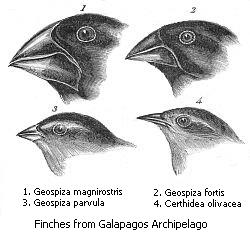

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic interactions or opens new environmental niches. Starting with a single ancestor, this process results in the speciation and phenotypic adaptation of an array of species exhibiting different morphological and physiological traits. The prototypical example of adaptive radiation is finch speciation on the Galapagos, but examples are known from around the world.

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, isolation and habitat area. Phytogeography is the branch of biogeography that studies the distribution of plants. Zoogeography is the branch that studies distribution of animals. Mycogeography is the branch that studies distribution of fungi, such as mushrooms.

Bergmann's rule is an ecogeographical rule that states that within a broadly distributed taxonomic clade, populations and species of larger size are found in colder environments, while populations and species of smaller size are found in warmer regions. Bergmann's rule only describes the overall size of the animals, but does not include body parts like Allen's rule does.

Stegodon is an extinct genus of proboscidean, related to elephants. It was originally assigned to the family Elephantidae along with modern elephants but is now placed in the extinct family Stegodontidae. Like elephants, Stegodon had teeth with plate-like lophs that are different from those of more primitive proboscideans like gomphotheres and mastodons. The oldest fossils of the genus are found in Late Miocene strata in Asia, likely originating from the more archaic Stegolophodon, shortly afterwards migrating into Africa. While the genus became extinct in Africa during the Pliocene, Stegodon remained widespread in Asia until the end of the Pleistocene.

Dwarf elephants are prehistoric members of the order Proboscidea which, through the process of allopatric speciation on islands, evolved much smaller body sizes in comparison with their immediate ancestors. Dwarf elephants are an example of insular dwarfism, the phenomenon whereby large terrestrial vertebrates that colonize islands evolve dwarf forms, a phenomenon attributed to adaptation to resource-poor environments and selection for early maturation and reproduction. Some modern populations of Asian elephants have also undergone size reduction on islands to a lesser degree, resulting in populations of pygmy elephants.

Insular biogeography or island biogeography is a field within biogeography that examines the factors that affect the species richness and diversification of isolated natural communities. The theory was originally developed to explain the pattern of the species–area relationship occurring in oceanic islands. Under either name it is now used in reference to any ecosystem that is isolated due to being surrounded by unlike ecosystems, and has been extended to mountain peaks, seamounts, oases, fragmented forests, and even natural habitats isolated by human land development. The field was started in the 1960s by the ecologists Robert H. MacArthur and E. O. Wilson, who coined the term island biogeography in their inaugural contribution to Princeton's Monograph in Population Biology series, which attempted to predict the number of species that would exist on a newly created island.

Leigh Van Valen was a U.S. evolutionary biologist. At the time of his death, he was professor emeritus in the Department of Ecology and Evolution at the University of Chicago.

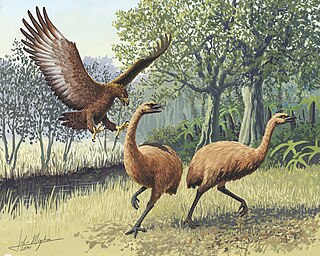

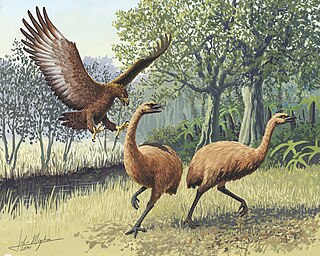

Island gigantism, or insular gigantism, is a biological phenomenon in which the size of an animal species isolated on an island increases dramatically in comparison to its mainland relatives. Island gigantism is one aspect of the more general "island effect" or "Foster's rule", which posits that when mainland animals colonize islands, small species tend to evolve larger bodies, and large species tend to evolve smaller bodies. This is itself one aspect of the more general phenomenon of island syndrome which describes the differences in morphology, ecology, physiology and behaviour of insular species compared to their continental counterparts. Following the arrival of humans and associated introduced predators, many giant as well as other island endemics have become extinct. A similar size increase, as well as increased woodiness, has been observed in some insular plants.

Insular dwarfism, a form of phyletic dwarfism, is the process and condition of large animals evolving or having a reduced body size when their population's range is limited to a small environment, primarily islands. This natural process is distinct from the intentional creation of dwarf breeds, called dwarfing. This process has occurred many times throughout evolutionary history, with examples including dinosaurs, like Europasaurus and Magyarosaurus dacus, and modern animals such as elephants and their relatives. This process, and other "island genetics" artifacts, can occur not only on islands, but also in other situations where an ecosystem is isolated from external resources and breeding. This can include caves, desert oases, isolated valleys and isolated mountains. Insular dwarfism is one aspect of the more general "island effect" or "Foster's rule", which posits that when mainland animals colonize islands, small species tend to evolve larger bodies, and large species tend to evolve smaller bodies. This is itself one aspect of island syndrome, which describes the differences in morphology, ecology, physiology and behaviour of insular species compared to their continental counterparts.

Island tameness is the tendency of many populations and species of animals living on isolated islands to lose their wariness of potential predators, particularly of large animals. The term is partly synonymous with ecological naïveté, which also has a wider meaning referring to the loss of defensive behaviors and adaptations needed to deal with these "new" predators. Species retain such wariness of predators that exist in their environment; for example, a Hawaiian goose retains its wariness of hawks, but does not exhibit such behaviors with mammals or other predators not found on the Hawaiian Islands. The most famous example is that of the dodo, which owed its extinction in a large part to a lack of fear of humans, and many species of penguin.

Hațeg Island was a large offshore island in the Tethys Sea which existed during the Late Cretaceous period, probably from the Cenomanian to the Maastrichtian ages. It was situated in an area corresponding to the region around modern-day Hațeg, Hunedoara County, Romania. Maastrichtian fossils of small-sized dinosaurs have been found in the island's rocks. It was formed mainly by tectonic uplift during the early Alpine orogeny, caused by the collision of the African and Eurasian plates towards the end of the Cretaceous. There is no real present-day analog, but overall, the island of Hainan is perhaps closest as regards climate, geology and topography, though still not a particularly good match. The vegetation, for example, was of course entirely distinct from today, as was the fauna.

The pygmy three-toed sloth, also known as the monk sloth or dwarf sloth, is a species of sloth in the family Bradypodidae. The species is endemic to Isla Escudo de Veraguas, a small island off the Caribbean coast of Panama. The species was first described by Robert P. Anderson of the University of Kansas and Charles O. Handley Jr., of the Smithsonian Institution in 2001. The pygmy three-toed sloth is significantly smaller than the other three members of its genus, but otherwise resembles the brown-throated three-toed sloth. According to Anderson and Handley Jr., the head-and-body length is between 48 and 53 centimetres, and the body mass ranges from 2.5 to 3.5 kg.

Rhabdodontidae is a family of herbivorous iguanodontian ornithopod dinosaurs whose earliest stem members appeared in the middle of the Lower Cretaceous. The oldest dated fossils of these stem members were found in the Barremian Castrillo de la Reina Formation of Spain, dating to approximately 129.4 to 125.0 million years ago. With their deep skulls and jaws, Rhabdodontids were similar to large, robust iguanodonts. The family was first proposed by David B. Weishampel and colleagues in 2003. Rhabdodontid fossils have been mainly found in Europe in formations dating to the Late Cretaceous.

The Theory of Island Biogeography is a 1967 book by the ecologist Robert MacArthur and the biologist Edward O. Wilson. It is widely regarded as a seminal piece in island biogeography and ecology. The Princeton University Press reprinted the book in 2001 as a part of the "Princeton Landmarks in Biology" series. The book popularized the theory that insular biota maintain a dynamic equilibrium between immigration and extinction rates. The book also popularized the concepts and terminology of r/K selection theory.

Island ecology is the study of island organisms and their interactions with each other and the environment. Islands account for nearly 1/6 of earth’s total land area, yet the ecology of island ecosystems is vastly different from that of mainland communities. Their isolation and high availability of empty niches lead to increased speciation. As a result, island ecosystems comprise 30% of the world’s biodiversity hotspots, 50% of marine tropical diversity, and some of the most unusual and rare species. Many species still remain unknown.

Balaur is a genus of theropod dinosaur from the late Cretaceous period, in what is now Romania. It is the type species of the monotypic genus Balaur, after the balaur, a dragon of Romanian folklore. The specific name bondoc means "stocky", so Balaur bondoc means "stocky dragon" in Romanian. This name refers to the greater musculature that Balaur had compared to its relatives. The genus, which was first described by scientists in August 2010, is known from two partial skeletons.

A biological rule or biological law is a generalized law, principle, or rule of thumb formulated to describe patterns observed in living organisms. Biological rules and laws are often developed as succinct, broadly applicable ways to explain complex phenomena or salient observations about the ecology and biogeographical distributions of plant and animal species around the world, though they have been proposed for or extended to all types of organisms. Many of these regularities of ecology and biogeography are named after the biologists who first described them.

Taxon cycles refer to a biogeographical theory of how species evolve through range expansions and contractions over time associated with adaptive shifts in the ecology and morphology of species. The taxon cycle concept was explicitly formulated by biologist E. O. Wilson in 1961 after he surveyed the distributions, habitats, behavior and morphology of ant species in the Melanesian archipelago.

Island syndrome describes the differences in morphology, ecology, physiology and behaviour of insular species compared to their continental counterparts. These differences evolve due to the different ecological pressures affecting insular species, including a paucity of large predators and herbivores as well as a consistently mild climate.

Kritimys, also known as the Cretan giant rat is an extinct genus of murid rodent that was endemic to the island of Crete during the Early and Middle Pleistocene. There are two known species, K. kiridus from the Early-Mid Pleistocene, and its descendant K. catreus from the Middle Pleistocene. It is suggested to be closely related to and probably derived from Praomys. As with most island rodents, Kritimys was larger than its mainland relatives, with its size increasing over time, with K. catreus esimated to weigh 518 grams (1.142 lb), around 6.7 times the weight of its mainland ancestor, an example of island gigantism. The temporal range of the genus is considered to define the regional Kritimys biozone, during which time there were only two other species of mammal native to the island, a species of dwarf mammoth, Mammuthus creticus and the dwarf hippopotamus Hippopotamus creutzburgi. It became extinct during the late Middle Pleistocene, following the arrival of the Mus bateae-minotaurus lineage to the island, exhibiting a decrease in size shortly before its extinction.