Big Pine Key is a census-designated place and unincorporated community in Monroe County, Florida, United States, on an island of the same name in the Florida Keys. As of the 2020 census, the town had a total population of 4,521.

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 is the primary law in the United States for protecting and conserving imperiled species. Designed to protect critically imperiled species from extinction as a "consequence of economic growth and development untempered by adequate concern and conservation", the ESA was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 28, 1973. The Supreme Court of the United States described it as "the most comprehensive legislation for the preservation of endangered species enacted by any nation". The purposes of the ESA are two-fold: to prevent extinction and to recover species to the point where the law's protections are not needed. It therefore "protect[s] species and the ecosystems upon which they depend" through different mechanisms. For example, section 4 requires the agencies overseeing the Act to designate imperiled species as threatened or endangered. Section 9 prohibits unlawful ‘take,’ of such species, which means to "harass, harm, hunt..." Section 7 directs federal agencies to use their authorities to help conserve listed species. The Act also serves as the enacting legislation to carry out the provisions outlined in The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). The Supreme Court found that "the plain intent of Congress in enacting" the ESA "was to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost." The Act is administered by two federal agencies, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). FWS and NMFS have been delegated by the Act with the authority to promulgate any rules and guidelines within the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) to implement its provisions.

The white-tailed deer, also known commonly as the whitetail and the Virginia deer, is a medium-sized species of deer native to North America, Central America, and South America as far south as Peru and Bolivia, where it predominately inhabits high mountain terrains of the Andes. It has also been introduced to New Zealand, all the Greater Antilles in the Caribbean, and some countries in Europe, such as the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, Romania and Serbia. In the Americas, it is the most widely distributed wild ungulate.

The mule deer is a deer indigenous to western North America; it is named for its ears, which are large like those of the mule. Two subspecies of mule deer are grouped into the black-tailed deer.

Wildlife conservation refers to the practice of protecting wild species and their habitats in order to maintain healthy wildlife species or populations and to restore, protect or enhance natural ecosystems. Major threats to wildlife include habitat destruction, degradation, fragmentation, overexploitation, poaching, pollution, climate change, and the illegal wildlife trade. The IUCN estimates that 42,100 species of the ones assessed are at risk for extinction. Expanding to all existing species, a 2019 UN report on biodiversity put this estimate even higher at a million species. It is also being acknowledged that an increasing number of ecosystems on Earth containing endangered species are disappearing. To address these issues, there have been both national and international governmental efforts to preserve Earth's wildlife. Prominent conservation agreements include the 1973 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). There are also numerous nongovernmental organizations (NGO's) dedicated to conservation such as the Nature Conservancy, World Wildlife Fund, the Wild Animal Health Fund and Conservation International.

Driftless Area National Wildlife Refuge is a United States National Wildlife Refuge in northeastern Iowa, southwestern Wisconsin and northwestern Illinois. It is a collection of non-contiguous parcels in the vicinity of the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge.

The Columbian white-tailed deer is one of the several subspecies of white-tailed deer in North America. It is a member of the Cervidae (deer) family, which includes mule deer, elk, moose, caribou, and the black-tailed deer that live nearby.

The National Key Deer Refuge is a 8,542-acre (34.57 km2) National Wildlife Refuge located on Big Pine Key and No Name Key in the Florida Keys in Monroe County, Florida.

The Key Largo woodrat, a subspecies of the eastern woodrat, is a medium-sized rat found on less than 2,000 acres of the northern area of Key Largo, Florida, in the United States. It is currently on the United States Fish and Wildlife Service list of endangered species. Only 6500 animals were thought to remain in North Key Largo in the late 1980s.

Fern Cave National Wildlife Refuge is a 199-acre (0.8 km2) National Wildlife Refuge located in northeastern Alabama, near Paint Rock, Alabama in Jackson County.

The Key West National Wildlife Refuge is a 189,497 acre (766.867 km2) National Wildlife Refuge located in Monroe County, Florida, between Key West, Florida and the Dry Tortugas. Only 2,019 acres (8.171 km2) of land are above sea level, on several keys within the refuge. These keys are unpopulated and are also designated as Wilderness within the Florida Keys Wilderness. The refuge was established to provide a preserve and breeding ground for native birds and other wildlife as well as to provide habitat and protection for endangered and threatened fish, wildlife, plants and migratory birds.

The St. Vincent National Wildlife Refuge is part of the United States National Wildlife Refuge System, located in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Apalachicola, on the barrier island of St. Vincent. The refuge includes Pig Island, located in the southwest corner of St. Joseph Bay, nearly 9 miles west of St. Vincent and 86 acres of mainland Florida along Franklin County Road 30A. The 12,490 acre (51 km2) refuge was established in 1968.

The Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge is part of the United States National Wildlife Refuge System, located in north Key Largo, less than 40 miles (64 km) south of Miami off SR 905. The 6,686 acre (27.1 km2) refuge opened during the year of 1980, under the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 and the Endangered Species Act of 1973. It was established in order to protect critical breeding and nesting habitat for the threatened American crocodile and other wildlife. This area also includes 650 acres (2.6 km2) of open water in and around the refuge. In addition to being one of only three breeding populations of the American crocodile, the refuge is home to tropical hardwood hammock, mangrove forest, and salt marsh. It is administered as part of the National Key Deer Refuge which is also located in the Florida Keys.

The Miami blue is a small butterfly that is native to coastal areas of southern Florida. It is a subspecies of Thomas's blue. Once common throughout its range, it has become critically endangered, and is considered to be near extinction. Its numbers have recently been increased by a captive breeding program at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Coccothrinax argentata, commonly called the Florida silver palm, is a species of palm tree. It is native to south Florida, southeast Mexico, Colombia and to the West Indies, where it is found in the Bahamas, the southwest Caribbean and the Turks and Caicos Islands. Its natural habitat is rocky, calcareous soil in coastal scrubland and hammock communities.

The Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge is a 9,125-acre (37 km2) National Wildlife Refuge made up of several parcels of land along 50 miles (80 km) of Maine's southern coast. Created in 1966, it is named for environmentalist and author Rachel Carson, whose book Silent Spring raised public awareness of the effects of DDT on migratory songbirds, and of other environmental issues.

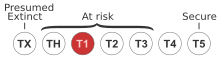

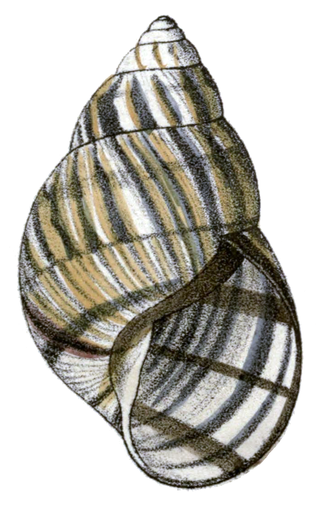

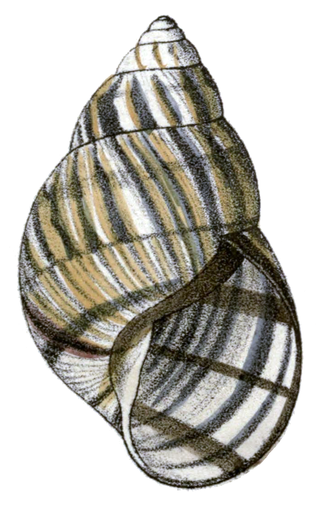

Orthalicus reses, the Stock Island tree snail, is a species of large tropical air-breathing tree snail, a terrestrial pulmonate gastropod mollusk in the family Orthalicidae. It was first described in 1830 by the American naturalist Thomas Say. The holotype, a specimen probably collected in Key West, was subsequently lost. Over a hundred years later, in 1946, the American biologist Henry Augustus Pilsbry redescribed the species using a specimen from Stock Island, Florida. Orthalicus reses has two subspecies, O. reses reses and O. reses nosodryas. The validity of these two taxa is still being discussed, but some experts argue that considering them as independent units may be important for management purposes.

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching, and invasive species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List lists the global conservation status of many species, and various other agencies assess the status of species within particular areas. Many nations have laws that protect conservation-reliant species which, for example, forbid hunting, restrict land development, or create protected areas. Some endangered species are the target of extensive conservation efforts such as captive breeding and habitat restoration.

Hilton Head white-tailed deer are a subspecies of white-tailed deer indigenous to Hilton Head Island in South Carolina. The deer live in a mainly suburban environment and have developed home range areas on the island.

The Key Largo cotton mouse is a subspecies of rodent in the family Cricetidae. The subspecies is endemic to Key Largo in the upper Florida Keys. It is a slightly larger mouse with a more reddish color than other mouse species from mainland Florida. The Key Largo cotton mouse can breed throughout the year and has an average life expectancy of five months.