The First Amendment to the United States Constitution prevents the government from making laws respecting an establishment of religion; prohibiting the free exercise of religion; or abridging the freedom of speech, the freedom of the press, the freedom of assembly, or the right to petition the government for redress of grievances. It was adopted on December 15, 1791, as one of the ten amendments that constitute the Bill of Rights.

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may include the freedom of conscience, freedom of press, freedom of religion, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, the right to security and liberty, freedom of speech, the right to privacy, the right to equal treatment under the law and due process, the right to a fair trial, and the right to life. Other civil liberties include the right to own property, the right to defend oneself, and the right to bodily integrity. Within the distinctions between civil liberties and other types of liberty, distinctions exist between positive liberty/positive rights and negative liberty/negative rights.

The Constitution of South Africa is the supreme law of the Republic of South Africa. It provides the legal foundation for the existence of the republic, it sets out the rights and duties of its citizens, and defines the structure of the Government. The current constitution, the country's fifth, was drawn up by the Parliament elected in 1994 in the South African general election, 1994. It was promulgated by President Nelson Mandela on 18 December 1996 and came into effect on 4 February 1997, replacing the Interim Constitution of 1993. The first constitution was enacted by the South Africa Act 1909, the longest-lasting to date. Since 1961, the constitutions have promulgated a republican form of government.

A secular state is an idea pertaining to secularity, whereby a state is or purports to be officially neutral in matters of religion, supporting neither religion nor irreligion. A secular state claims to treat all its citizens equally regardless of religion, and claims to avoid preferential treatment for a citizen based on their religious beliefs, affiliation or lack of either over those with other profiles.

Freedom of religion in Canada is a constitutionally protected right, allowing believers the freedom to assemble and worship without limitation or interference.

Freedom of education is the right for parents to have their children educated in accordance with their religious and other views, allowing groups to be able to educate children without being impeded by the nation state.

Chapter Two of the Constitution of South Africa contains the Bill of Rights, a human rights charter that protects the civil, political and socio-economic rights of all people in South Africa. The rights in the Bill apply to all law, including the common law, and bind all branches of the government, including the national executive, Parliament, the judiciary, provincial governments, and municipal councils. Some provisions, such as those prohibiting unfair discrimination, also apply to the actions of private persons.

The Fundamental Rights in India enshrined in part III of the Constitution of India guarantee civil liberties such that all Indians can lead their lives in peace and harmony as citizens of India. These rights are known as "fundamental" as they are the most essential for all-round development i.e., material, intellectual, moral and spiritual and protected by fundamental law of the land i.e. constitution. If the rights provided by Constitution especially the Fundamental rights are violated the Supreme Court and the High Courts can issue writs under Articles 32 and 226 of the Constitution, respectively, directing the State Machinery for enforcement of the fundamental rights.

Religion in South Africa is dominated by various branches of Christianity, which collectively represent around 78% of the country's total population.

The Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act, 2000 is a comprehensive South African anti-discrimination law. It prohibits unfair discrimination by the government and by private organisations and individuals and forbids hate speech and harassment. The act specifically lists race, gender, sex, pregnancy, family responsibility or status, marital status, ethnic or social origin, HIV/AIDS status, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth as "prohibited grounds" for discrimination, but also contains criteria that courts may apply to determine which other characteristics are prohibited grounds. Employment discrimination is excluded from the ambit of the act because it is addressed by the Employment Equity Act, 1998. The act establishes the divisions of the High Court and designated Magistrates' Courts as "Equality Courts" to hear complaints of discrimination, hate speech and harassment.

The Constitution provides for freedom of religion, although it prohibits what the Government considers to be religious fundamentalism.

Article 15 of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore guarantees freedom of religion in Singapore. Specifically, Article 15(1) states: "Every person has the right to profess and practise his religion and to propagate it."

Iain Tyrrell Benson is a legal philosopher and practising legal consultant. The main focus of his work in relation to law and society has been to examine some of the various meanings that underlie terms of common but confused usage. His work towards an understanding of secular and secularism has been cited by the Supreme Court of Canada and the Constitutional Court of South Africa. He has also given critical study to the terms pluralism, faith, believer, unbeliever, liberalism and accommodation and examined the implications for various legal and non-legal usages.

The South African Charter of Religious Rights and Freedoms (SACRRF) is a charter of rights drawn up by South African religious and civil organisations which is intended to define the religious freedoms, rights and responsibilities of South African citizens. The aim of the drafters of the charter is for it to be approved by Parliament in terms of section 234 of the Constitution of South Africa.

Christian Education South Africa v Minister of Education is an important case in South African law. It was heard in the Constitutional Court, by Chaskalson P, Langa DP, Goldstone J, Madala J, Mokgoro J, Ngcobo J, O'Regan J, Sachs J, Yacoob J and Cameron AJ, on 4 May 2000, with judgment handed down on 18 August. FG Richings SC appeared for the appellant, and MNS Sithole SC for the respondent.

Neopaganism in South Africa is primarily represented by the traditions of Wicca, Neopagan witchcraft, Germanic neopaganism and Neo-Druidism. The movement is related to comparable trends in the United States and Western Europe and is mostly practiced by White South Africans of urban background; it is to be distinguished from folk healing and mythology in local Bantu culture.

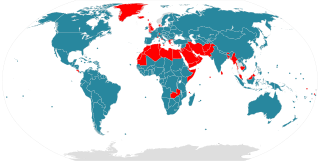

The status of religious freedom in Africa varies from country to country. States can differ based on whether or not they guarantee equal treatment under law for followers of different religions, whether they establish a state religion, the extent to which religious organizations operating within the country are policed, and the extent to which religious law is used as a basis for the country's legal code.

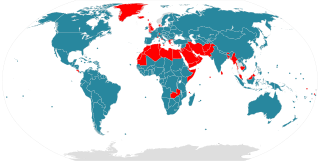

The status of religious freedom in South America varies from country to country. States can differ based on whether or not they guarantee equal treatment under law for followers of different religions, whether they establish a state religion, the extent to which religious organizations operating within the country are policed, and the extent to which religious law is used as a basis for the country's legal code.

Freedom of Religion South Africa is a South African nonprofit fundamentalist Christian advocacy group. It was founded in 2014 by Andrew Selley, the lead pastor and founder of the Joshua Generation Church, after parents filed a complaint to the South African Human Rights Commission that alleged that Joshua Generation Church advocated for corporal punishment in the home. In Freedom of Religion South Africa v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development, FOR SA unsuccessfully opposed a ruling by the Johannesburg High Court that deemed corporal punishment to be assault.

Qwelane v South African Human Rights Commission and Another is a 2021 decision of the Constitutional Court of South Africa on the constitutionality of a statutory prohibition on hate speech. The court found that section 10(1) of the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act 4 of 2000 was unconstitutional insofar as it included the vague term "hurtful" as part of the definition of prohibited hate speech.