Psychoanalysis is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques that deal in part with the unconscious mind, and which together form a method of treatment for mental disorders. The discipline was established in the early 1890s by Sigmund Freud, whose work stemmed partly from the clinical work of Josef Breuer and others. Freud developed and refined the theory and practice of psychoanalysis until his death in 1939. In an encyclopedia article, he identified the cornerstones of psychoanalysis as "the assumption that there are unconscious mental processes, the recognition of the theory of repression and resistance, the appreciation of the importance of sexuality and of the Oedipus complex." Freud's colleagues Alfred Adler and Carl Gustav Jung developed offshoots of psychoanalysis which they called individual psychology (Adler) and Analytical Psychology (Jung), although Freud himself wrote a number of criticisms of them and emphatically denied that they were forms of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis was later developed in different directions by neo-Freudian thinkers, such as Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, and Harry Stack Sullivan.

Sigmund Freud was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies seen as originating from conflicts in the psyche, through dialogue between patient and psychoanalyst, and the distinctive theory of mind and human agency derived from it.

Emma Eckstein (1865–1924) was an Austrian author. She was "one of Sigmund Freud's most important patients and, for a short period of time around 1897, became a psychoanalyst herself". She has been described as "the first woman analyst", who became "both colleague and patient" for Freud. As analyst, while "working mainly in the area of sexual and social hygiene, she also explored how 'daydreams, those "parasitic plants", invaded the life of young girls'."

Wilhelm Fliess was a German otolaryngologist who practised in Berlin. He developed the pseudoscientific theory of human biorhythms and a possible nasogenital connection that have not been accepted by modern scientists. He is today best remembered for his close friendship and theoretical collaboration with Sigmund Freud, a controversial chapter in the history of psychoanalysis.

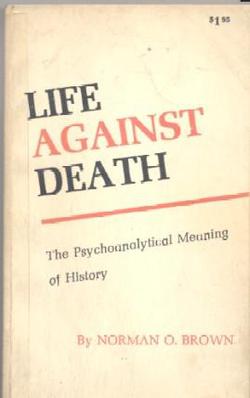

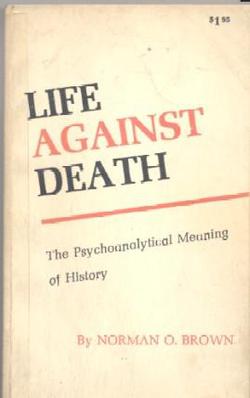

Life Against Death: The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History is a book by the American classicist Norman O. Brown, in which the author offers a radical analysis and critique of the work of Sigmund Freud, tries to provide a theoretical rationale for a nonrepressive civilization, explores parallels between psychoanalysis and Martin Luther's theology, and draws on revolutionary themes in western religious thought, especially the body mysticism of Jakob Böhme and William Blake. It was the result of an interest in psychoanalysis that began when the philosopher Herbert Marcuse suggested to Brown that he should read Freud.

Eros and Civilization: A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud is a book by the German philosopher and social critic Herbert Marcuse, in which the author proposes a non-repressive society, attempts a synthesis of the theories of Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud, and explores the potential of collective memory to be a source of disobedience and revolt and point the way to an alternative future. Its title alludes to Freud's Civilization and Its Discontents (1930). The 1966 edition has an added "political preface".

Frederick Campbell Crews is an American essayist and literary critic. Professor emeritus of English at the University of California, Berkeley, Crews is the author of numerous books, including The Tragedy of Manners: Moral Drama in the Later Novels of Henry James (1957), E. M. Forster: The Perils of Humanism (1962), and The Sins of the Fathers: Hawthorne's Psychological Themes (1966), a discussion of the work of Nathaniel Hawthorne. He received popular attention for The Pooh Perplex (1963), a book of satirical essays parodying contemporary casebooks. Initially a proponent of psychoanalytic literary criticism, Crews later rejected psychoanalysis, becoming a critic of Sigmund Freud and his scientific and ethical standards. Crews was a prominent participant in the "Freud wars" of the 1980s and 1990s, a debate over the reputation, scholarship, and impact on the 20th century of Freud, who founded psychoanalysis.

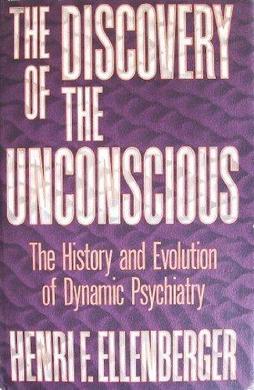

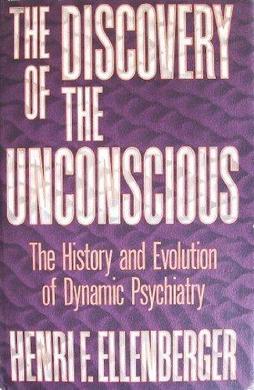

The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry is a 1970 book about the history of dynamic psychiatry by the Swiss medical historian Henri F. Ellenberger, in which the author discusses such figures as Franz Anton Mesmer, Sigmund Freud, Pierre Janet, Alfred Adler, and Carl Jung. The book was first published in the United States by Basic Books. The work has become a classic, and has been credited with correcting older estimates of Freud's level of originality and encouraging scholars to question the scientific validity of psychoanalysis.

Knowledge and Human Interests is a 1968 book by the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas, in which the author discusses the development of the modern natural and human sciences. He criticizes Sigmund Freud, arguing that psychoanalysis is a branch of the humanities rather than a science, and provides a critique of the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

Why Freud Was Wrong: Sin, Science and Psychoanalysis is a book by Richard Webster, in which the author provides a critique of Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis, and attempts to develop his own theory of human nature. Webster argues that Freud became a kind of Messiah and that psychoanalysis is a pseudoscience and a disguised continuation of the Judaeo-Christian tradition. Webster endorses Gilbert Ryle's arguments against mentalist philosophies in The Concept of Mind (1949), and criticizes many other authors for their treatment of Freud and psychoanalysis.

The Assault on Truth: Freud's Suppression of the Seduction Theory is a book by the former psychoanalyst Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, in which the author argues that Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, deliberately suppressed his early hypothesis, known as the seduction theory, that hysteria is caused by sexual abuse during infancy, because he refused to believe that children are the victims of sexual violence and abuse within their own families. Masson reached this conclusion while he had access to several of Freud's unpublished letters as projects director of the Sigmund Freud Archives. The Assault on Truth was first published in 1984 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux; several revised editions have since been published.

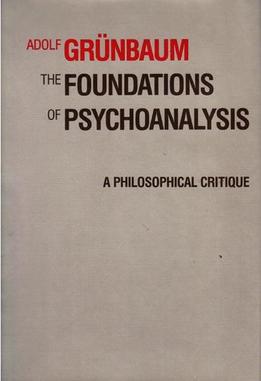

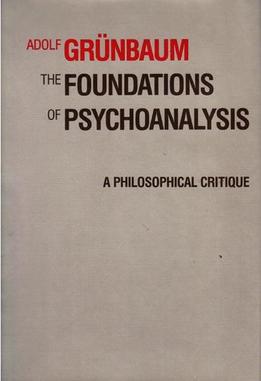

The Foundations of Psychoanalysis: A Philosophical Critique is a 1984 book by the philosopher Adolf Grünbaum, in which the author offers a philosophical critique of the work of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. The book was first published in the United States by the University of California Press. Grünbaum evaluates the status of psychoanalysis as a natural science, criticizes the method of free association and Freud's theory of dreams, and discusses the psychoanalytic theory of paranoia. He argues that Freud, in his efforts to defend psychoanalysis as a method of clinical investigation, employed an argument that Grünbaum refers to as the "Tally Argument"; according to Grünbaum, it rests on the premises that only psychoanalysis can provide patients with correct insight into the unconscious pathogens of their psychoneuroses and that such insight is necessary for successful treatment of neurotic patients. Grünbaum argues that the argument suffers from major problems. Grünbaum also criticizes the views of psychoanalysis put forward by other philosophers, including the hermeneutic interpretations propounded by Jürgen Habermas and Paul Ricœur, as well as Karl Popper's position that psychoanalytic propositions cannot be disconfirmed and that psychoanalysis is therefore a pseudoscience.

Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation is a 1965 book about Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, written by the French philosopher Paul Ricœur. In Freud and Philosophy, Ricœur interprets Freudian work in terms of hermeneutics, a theory that governs the interpretation of a particular text, and phenomenology, a school of philosophy founded by Edmund Husserl. Ricœur addresses questions such as the nature of interpretation in psychoanalysis, the understanding of human nature and the relationship between Freud's interpretation of culture amongst other interpretations. The book was first published in France by Éditions du Seuil, and in the United States by Yale University Press.

The Memory Wars: Freud's Legacy in Dispute is a 1995 book that reprints articles by the critic Frederick Crews critical of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, and recovered-memory therapy. It also reprints letters from Harold P. Blum, Marcia Cavell, Morris Eagle, Matthew Erdelyi, Allen Esterson, Robert R. Holt, James Hopkins, Lester Luborsky, David D. Olds, Mortimer Ostow, Bernard L. Pacella, Herbert S. Peyser, Charlotte Krause Prozan, Theresa Reid, James L. Rice, Jean Schimek, and Marian Tolpin.

Decline and Fall of the Freudian Empire is a book by the psychologist Hans Eysenck, in which the author criticizes Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. Eysenck argues that psychoanalysis is unscientific. The book received both positive and negative reviews. Eysenck has been criticized for his discussion of the physician Josef Breuer's treatment of his patient Anna O., whom Eysenck argues suffered from tuberculous meningitis.

Freud: The Mind of the Moralist is a book about Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, by the sociologist Philip Rieff, in which the author places Freud and psychoanalysis in historical context. Rieff described his goal as being to "show the mind of Freud ... as it derives lessons on the right conduct of life from the misery of living it."

A History of the Mind: Evolution and the Birth of Consciousness is a 1992 book about the mind–body problem by the psychologist Nicholas Humphrey. Humphrey advances a hypothesis about consciousness that has been criticised as speculative.

The Freudian Fallacy, first published in the United Kingdom as Freud and Cocaine, is a 1983 book about Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, by the medical historian Elizabeth M. Thornton, in which the author argues that Freud became a cocaine addict and that his theories resulted from his use of cocaine. The book received several negative reviews, and some criticism from historians, but has been praised by authors critical of Freud and psychoanalysis. The work has been compared to Jeffrey Masson's The Assault on Truth (1984).

Sexuality and Its Discontents: Meanings, Myths, and Modern Sexualities is a 1985 book about the politics and philosophy of sex by the sociologist Jeffrey Weeks. The book received positive reviews, crediting Weeks with explaining the theories of sexologists and usefully discussing controversial sexual issues. However, Weeks was criticised for his treatment of feminism and sado-masochism.

Philosophical Essays on Freud is a 1982 anthology of articles about Sigmund Freud and psychoanalysis edited by the philosophers Richard Wollheim and James Hopkins. Published by Cambridge University Press, it includes an introduction from Hopkins and an essay from Wollheim, as well as selections from philosophers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein, Clark Glymour, Adam Morton, Stuart Hampshire, Brian O'Shaughnessy, Jean-Paul Sartre, Thomas Nagel, and Donald Davidson. The essays deal with philosophical questions raised by the work of Freud, including topics such as materialism, intentionality, and theories of the self's structure. They represent a range of different viewpoints, most of them from within the tradition of analytic philosophy. The book received a mixture of positive, mixed, and negative reviews. Commentators found the contributions included in the book to be of uneven value.